The Exploitation of Labor and Other Union Myths

This is the full text of remarks I delivered at the University of Colorado-Boulder on March 14, 2019 at the invitation of the Center for Western Civilization, Thought & Policy (here). The video of the lecture is here.

I am honored to be here at the University of Colorado, and wish to thank Professor Stephen Presser for the kind—and brave–invitation. He went out on a limb by inviting someone to lecture who is not a traditional academic. I am a retired lawyer who now engages in “legal commentary” as a writer and blogger. My principal area of law during 30 years of practice was labor and employment, and I’ll address some widely-held misconceptions about that subject momentarily.

My intent is to expose you to some points of view with which you may be unfamiliar. I come not as a provocateur, in the mold of Milo Yiannopoulos, or a proselytizer, but as an intellectual pilgrim offering a travelogue of ideas. Or perhaps an archeologist displaying some fossils. I hope to pique your interest enough to make you want to engage in further inquiry on your own. That is why you are in college—to explore the world of ideas. I want to exhort you to keep an open mind—to be receptive to considering new perspectives. To be curious, and a bit skeptical. To investigate and make up your own mind.

So, let’s turn to the main focus of my remarks: several widely-held misconceptions about the “exploitation of labor” and more generally about labor unions in America.

What is the point of talking about unions? For one thing, the subject is both vitally important and poorly understood. Labor relations necessarily requires exploration of first principles: what is the origin of “rights,” and how should individuals interact in a free society? On a more concrete level, “class” differences are embedded in modern political thought and animate much of the current progressive agenda. Many people instinctively believe that individual employees are “powerless” and “oppressed,” and therefore need either collective action or external assistance (or both) to ensure fairness in the labor market. This type of thinking is behind many of the “living wage,” “guaranteed income,” and $15/hour minimum wage proposals, or even more radical proposals—the agenda of “democratic socialism.”

Moreover, unions have been, and remain, important forces in American life, both economically and politically. And understanding the background of the union movement in America requires some knowledge of neglected aspects of politics, economics, government, history, and law.

One of the challenges in this area is to overcome the pro-union (or anti-capitalist) bias that is prevalent among labor law scholars and labor historians. [1]

Terminology and Concepts

As a “classical liberal,” I proceed from the premise that, in the “state of nature,” all men are born free and are endowed by their Creator with self-ownership—that is, their labor, and the direct fruits of their labor, belong to them. The opposite of self-ownership is slavery, servitude, or serfdom. Self-ownership leads to recognition of the institution of private property. One owns what one produces, or acquires through consensual exchange. When entering into civil society, pursuant to a fictitious (but essential) social contract, men surrender some of their natural rights in exchange for the protection of laws. Our state and federal constitutions represent the terms of this “bargain.” My premise is inspired by our Declaration of Independence, and is consistent with the Lockean concepts that influenced the Founding Fathers.

In a society based on individual liberty, limited government, and the protection of private property, the ideal form of interaction among men is consensual economic exchanges, which protect freedom and maximize economic efficiency. Force and coercion are the opposite of voluntary actions. Free market economics—or laissez-faire–places great emphasis on competition, which in theory produces the lowest prices, benefiting consumers. Adam Smith’s classic book, The Wealth of Nations (1776), was the seminal statement of classical economics—the foundation for what became known as capitalism.

To protect competition, our antitrust laws forbid monopolies, price-fixing arrangements, and other restraints on trade. Businessmen cannot legally agree to set prices, divide markets, or otherwise collude in a way that would reduce competition. From an economic perspective, labor is indistinguishable from any other commodity bought and sold in the market. [2] Wages are merely the “price” of labor, and in a free market they would be determined by a consensual exchange between buyer (employer) and seller (employee) as the result of competition.

What are unions? Unions are not social groups or fraternal organizations, like the Rotary or Kiwanis clubs. Formerly known as guilds, they are the collectivized agent of workers, organized to obtain higher wages and more favorable working conditions than workers could obtain on their own, through competition. How, exactly, does this happen? Unions essentially operate as cartels, fixing the price of their members’ labor by internal collusion, rather than market competition–just like OPEC nations fix the price of a barrel of oil, rather than letting the market set the price. [3] The internal price-fixing for labor is called “collective bargaining.”

Like OPEC, unions threaten to withhold supply if the buyer does not agree to pay the “fixed” price. This is called a “strike.” Unlike OPEC, however, unions attempt to prevent other sellers (who are not members of the cartel) from selling at a lower price, sometimes with the threat of violence. This is called a “picket line.” [4] Strikers not only collectively withhold their own services (which is consensual), they seek to prevent other workers from crossing the picket line (through force or coercion). Unions call these people “strike breakers” or “scabs,” but they are merely sellers willing to accept a lower wage—a function of competition and consensual exchange—which is entirely legitimate in a free society. [5]

If OPEC countries tried to blockade shipping to the United States to prevent the delivery of oil from non-OPEC suppliers, we would quite properly regard it as an act of war. Among unionized workers, the same behavior is celebrated as “solidarity.”

Also, unions, unlike OPEC, depend on government coercion. Employers are required to “recognize” unions once they are “elected” by a majority of the employees; employers are required to negotiate exclusively with the union before taking action regarding the employees; employers are prohibited from firing employees because of their union involvement; and employers are prohibited from replacing striking workers under certain circumstances. All of these are significant restrictions on the common law rights—and economic freedoms–enjoyed by employers prior to the enactment of federal labor laws, beginning in 1935.

The reason we have labor unions—to establish “industrial democracy”—is purportedly to overcome the inherent “inequality of bargaining power” that is thought to exist between capital and labor. The legislative “findings” in support of the National Labor Relations Act so state. [6] This controversial notion, resting on half-baked socialist premises, has dubious origins and has had far-reaching implications for labor law. Because this is a lecture rather than a semester-long course, I will keep my treatment of the subject somewhat general, and try to avoid the weeds. [7]

Myth #1: Inequality of Bargaining Power

Classical free market economics holds that workers “sell” their services to employers in a labor market in which the “efficient” wage rate is determined by competition among both buyers and sellers. The specific wage “bargain” that is struck will depend on the worker’s perceived value to the employer and the existence of competing offers by other employers. In the world of free markets, the government’s main role is to punish fraud, enforce contracts, and prevent collusion. Labor unions, which exist to facilitate collusion among sellers, are neither required nor encouraged. Critics of free market economics had a different view—sometimes radically so.

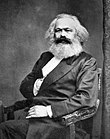

Karl Marx, the author of The Communist Manifesto (1848) (co-authored by Friedrich Engels) and Das Kapital (1867), is often credited as the intellectual father of modern (or “scientific”) socialism. Marx believed that capital (the owners of businesses) and labor (consisting of the working men employed by businesses) represent separate, antagonistic classes, and that the employment relationship is inherently exploitative because workers in a capitalist society are forced to sell their labor power to capitalists for less than the full value of the commodities they produce with their labor. Capital’s ownership of the “means of production” allows business owners to extract the “full” value of workers’ labor (i.e., the price of the finished product) while paying them for only the “commodity” value of their services (i.e., an hourly wage rate). The added value is assumed to belong to the workers, and the employers’ resulting profit is wholly undeserved. Marxian theory assumes that capital owners contribute nothing to the process of production. [8]

From a Marxian perspective, profiting from capital is illegitimate—equivalent to stealing. By retaining the “surplus” value of workers’ labor, capital exploits the workers, an injustice that can only be corrected if the workers seize ownership of the businesses and therefore dispense with the parasitical role of capital. For Marx, class struggle, leading to revolution and seizure of the “means of production,” is the only way to prevent the exploitation of labor. Private property ownership is therefore incompatible with Marxian theory. Employment by a profit-making business constitutes oppression. This extreme form of socialism is the foundation of Communism. One can just imagine how militant workers would be if they sincerely believed Marxian rhetoric, as many did during the heyday of the Industrial Revolution. They were incited to revolt and overthrow the established order, by force if necessary.

In the late 19th century, as industrialism was burgeoning in America (and continued in England), Marx’s conception of socialism began to become associated in the public mind with violent anarchism—an unfavorable connection—leading non-revolutionary socialists to embrace a “kinder, gentler” version of Marx’s theory, some versions of which pre-dated Marx. This school of thought, symbolized by the Fabian Society in London (founded in 1884), became the basis for England’s Labour Party and the London School of Economics. Some of the prominent figures associated with “Fabian Socialism” include Sidney and Beatrice Webb and, in the so-called “second generation,” Harold Laski, who was a lifelong friend and correspondent of Professor Presser’s bête noire, the American jurist and renowned “Legal Realist” Oliver Wendell Holmes. [9]

Non-revolutionary socialism, or “democratic socialism,” inspired much of 20th century labor union theory, which was sometimes aligned with a movement known as syndicalism. The more moderate brand of socialism did not call for outright worker ownership of the “means of production,” but emphasized the need for concerted action by employees to rectify the purported “inequality of bargaining power” between labor and capital (sometimes blamed on the ability of capital to organize into corporate entities), and to exercise some control of the business through union negotiations. Empowering workers in this way would, it was thought, prevent capital from earning “excessive” profits. This is the genesis of the modern American labor union movement, and forms the gist of trade union rhetoric.

It is a fallacy to ignore—or deny—the crucial role of capital. Prior to industrialization, and the division of labor in the form of specialized trades, nearly every man toiled the land. If he owned the land outright, the crops he grew were his property. If he toiled on the land of another, he either paid rent or shared his crop with the owner (hence the term “sharecropper”). As trades developed, blacksmiths, cobblers, weavers, and the like either had the resources to acquire their own tools and supplies, or had to rely on another to furnish these items—capital goods. The former is his own master; the latter an apprentice or workman in the employ of another. The workman had to share the bounty of his labor with the provider of capital, on terms agreeable to both. This is the conceptual origin of the modern employment relationship. It is intellectually dishonest to skip from an agricultural economy to the factory system, and deny the factory owner any credit for amassing the capital, devising the machines, and incurring the risk that made the enterprise possible.

In any event, is there an inherent inequality between labor and capital? The classical economic model holds otherwise. As long as there is competition between buyers and sellers, and the absence of external coercion, the “equilibrium” price struck through voluntary exchange will represent the “efficient” market-clearing wage, favoring neither side. It doesn’t matter, as a matter of economic theory, whether the buyer (employer) is an individual, sole proprietorship, partnership, or corporation. The principle is the same. Does an individual consumer have a disadvantage in Wal-Mart or on Amazon as compared to shopping in a Middle Eastern bazaar? Of course not. As a matter of economics, labor is a commodity, and the proclamation to the contrary in the 1914 Clayton Act [10] is simply a protectionist measure reciting the vernacular of socialist dogma.

Depending on the employee’s skill, experience, industry, and productivity, wage rates will vary across the workforce and across different industries. In today’s economy, without union representation, some brand new lawyers earn starting salaries approaching $200,000/year, computer programmers can demand valuable stock options from the high-tech companies they work for, and welders and other trades in the oil patch earn in the six figures. Hollywood stars, professional athletes, and recording artists sometimes earn tens of millions of dollars annually—or more. Judge Judy makes $47 million a year, more than any other TV host. LeBron James, who never attended college, recently signed a four-year, $154 million contract with the L.A. Lakers. Twenty-six year-old free agent Manny Machado just signed a 10-year deal with the San Diego Padres worth $300 million. Another ballplayer, Bryce Harper, recently inked a deal with the Philadelphia Phillies worth $330 million over 13 years. Where is the “inequality of bargaining power”?

In a free society, compensation is determined by supply and demand. Some people’s labor is more valuable than others. The notion that labor is fungible, that individuals are inevitably at a disadvantage vis-à-vis corporations, and that employment is inherently “exploitative” is a vestige of Marxian theory that has been discredited by history. Consider Venezuela and the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Myth #2: Capitalism Oppressed Workers

Why, then, does the mythology of “industrial democracy” persist? There are many explanations, but in keeping with my iconoclastic theme I will contend that it aids the political left’s self-serving defense of rent-seeking by one of its major constituent groups–workers. Unions are a core member of the Democratic Party’s political coalition. The working class has functioned as a faction for hundreds of years, and has been romanticized for just as long. Charles Dickens made his career by sympathetically depicting the plight of the downtrodden in Victorian London. Class conflict is a favorite theme for liberals. The Left has developed a narrative that the rise of capitalism—and particularly the Industrial Revolution—resulted in the oppression of workers, but this is false. Capitalism liberated the long-suffering peasant class.

Ever since the advent of the Industrial Revolution (beginning in England in the late 18th century), a population that for centuries had subsisted—sometimes barely or not at all—primarily on labor-intensive agricultural production increasingly became engaged in factory production. This was a momentous shift. Technology, enabled by capital investment and the profit motive, transformed the economy. Factories, machinery, innovation, and inventions (including the steam engine) wrought dramatic social changes. These developments concentrated workers in centralized activities and shifted the population mix from rural to urban locations. Cities grew rapidly. Trade expanded. People often relocated to pursue opportunities, and the sheer number of people vastly increased due to sharply-declining mortality rates.

Even though industrialism in the long run improved workers’ standard of living significantly—which is a relative improvement made all the more dramatic by the squalor, hunger, disease, and poverty that afflicted most people in the pre-industrial era—living in closer quarters and observing the prosperity being enjoyed by the emerging business and professional classes (the “bourgeoisie” in Marxian terms) created tensions and resentments. Unionism was primarily a manifestation of workers’ dissatisfaction with relative inequality.

While wage-paid factory workers—the “proletariat,” in Marxian terms–were generally better off than prior generations of serfs, or tenant farmers, or miners, or wool spinners and weavers, who had barely eked out a living by piece work, they saw others with more and were prompted to demand a greater share for themselves. Increased class consciousness and the proximity of large groups of similarly-situated workers begat industrial discontent. This ultimately explains the rise of unionism in England, and in the U.S. a century later when the Industrial Age came to America.

As a matter of history, the “oppression” of the working man as a result of the Industrial Revolution was instead a steady improvement in the average standard of living, [11] along with a declining incidence of child labor. In the U.S., average real wages grew significantly-to-substantially in the decades 1860-1910, an era of large-scale immigration, immense capital investment, and technological change, while the percentage of the labor force that was unionized was minuscule. This is exactly the opposite of what exploitation theory would have us believe. [12] The main goal of unions, then and now, is to artificially increase economically efficient wage rates (and simultaneously to reduce productivity) by threatening to disrupt the employer’s operations through strikes and other forms of work stoppages.

Regardless of the myth, the political struggle between the “haves” and the “have nots” animated the Progressive Movement, coalesced during the New Deal, and continues to this day. Envy, once regarded as one of the “seven deadly sins,” is now a centerpiece of the progressive agenda.

Myth #3: Employers Were Wrong to Resist Unionization

Union advocates often cite as evidence of industrial oppression the resistance of employers to unionization, which they claim was typically characterized by violence. Congress cited the refusal of some employers to recognize unions and to engage in collective bargaining as a justification for enacting the NLRA. It is a fallacy to assume that employers violated employees’ rights simply by declining to accede to union demands. Recall the previous discussion of competition and free markets. Absent force or fraud, consensual economic arrangements violate no one’s “rights.” Prior to the New Deal (and in particular the NLRA), businesses could operate largely as they pleased, subject to antitrust laws and common law rules. A unionized work force was legitimately viewed as a serious impediment to operating a profitable business. It is entirely understandable why a factory owner—then and now—would oppose unionization.

First of all, without a union, employment is “at will,” or on other terms agreed to between the individual worker and the employer. The worker was generally free to quit at any time, and the employer had the concomitant right to terminate the employment relationship. The employer set the work schedule, which commonly was 10 hours a day, six days a week, and job security was non-existent or close to it. If business slowed down, employees would be laid off. Federally-mandated overtime laws and similar protections were decades off.

A union claiming to represent the workers would typically demand higher wages and more generous benefits, for a shorter work week, with protections against layoffs and restrictions on operations. Employers understandably viewed such demands as a meddlesome interference with their businesses, and refused to negotiate with the unions. Agreeing to such terms would raise labor costs, placing a business at a competitive disadvantage vis-à-vis other firms. Even small differentials in cost between firms could be ruinous. When the unions struck—engaged in a concerted refusal to work, and usually interfering with the ability of other workers to take their place–employers hired private security and understandably made sure the replacement workers could fill the jobs. This response is neither unreasonable or morally objectionable.

During the Gilded Age, and even as late as the 1930s, many employers conditioned employment offers on employees’ agreement not to join a union. These arrangements are pungently referred to as “yellow-dog contracts,” on the grounds that signing such a pledge supposedly reduces a worker to the status of a yellow dog, but it is merely the flipside of a “closed” shop agreement, which limits employment to union members. (The closed shop, once common, was not prohibited until 1947.) There is nothing intrinsically wrong—let alone immoral—about employers requiring workers to agree to refrain from union membership as a condition of employment, so long as they are consensual.

Myth #4: Employers Were Primarily Responsible for Violence in Labor Disputes

While it is true that many labor conflicts were violent–especially during the tumultuous late 1800s and early 1900s, at the peak of the so-called Gilded Age–labor unions were responsible for most of the violence. Violent conflict was most common when replacement workers (or “scabs”) tried to cross the picket lines—as they had a legal right to. The very term “scab” expresses the extraordinary contempt that union sympathizers had for workers who did not share their collective goals—i.e., who were willing to work on terms that the union refused. Much is said about employers hiring private security forces (such as Pinkertons) to provide security, which they did in the absence of adequate local police forces to protect their property during that time, but one must not overlook the militant leadership of many labor unions during this era, which included a radical faction of socialists, communists, and anarchists who sought to overthrow the capitalistic system. Unionists, many of whom embraced the Marxian conception that private ownership of businesses was illegitimate, were willing to—and did–resort to extreme measures. Bombings were not uncommon.

Let’s take a quick look at one of the most notorious labor conflicts, the May 4, 1886 riot in Chicago’s Haymarket Square, in which eight people (including seven Chicago police officers) were killed when someone threw a bomb into a crowd of policemen who were breaking up a protest rally. Conventional wisdom holds that xenophobia and anti-union hysteria led to an unfair trial resulting in the conviction of eight foreign-born anarchists, four of whom were hanged—a travesty of justice, according to historians sympathetic to the labor movement. I would recommend that you read Timothy Messer-Kruse’s scrupulously-balanced account, The Trial of the Haymarket Anarchists (2011) for an alternative version, based on a review of the actual trial transcript—previously unexamined by historians. His assessment: The investigation was thorough, the lengthy (six week!) trial was fair, the evidence was overwhelming, and the jury verdict was sound.

If you look at the history of labor unions in America, you will find many radical outfits that advocated and engaged in extreme violence, including the Industrial Workers of the World (“Wobblies”), the Iron Workers Union (responsible for bombing the L.A. Times building in 1910), the Western Federation of Miners (charged with assassinating Idaho Governor Frank Steunenberg in 1905), and the United Mine Workers, which led an armed insurrection in West Virginia in 1920-21 resulting in up to 100 deaths before being suppressed by federal troops. The Pullman Strike (and boycott) in 1894 was a violent affair led by socialist Eugene Debs, then-President of the American Railway Union, who was imprisoned for defying court orders. And there are many others. I don’t wish to suggest that employers were always blameless, or that peaceful picketers were never the victims of violence, only that both sides bear responsibility.

Unions have never hesitated to resort to force, or physically to interfere with the employers’ business operations, often in violation of the law. The UAW obtained General Motors’ recognition in Flint, Michigan by staging an illegal sit-down strike in 1936-37, and defying federal court orders that they vacate GM’s premises.

The Gilded Age witnessed all manner of upheaval and social and economic change, including huge amounts of immigration and what by modern standards appears to be inhumane working and living conditions, in New York City and elsewhere. Conditions were often grim. There is a temptation to look back on history as a struggle between villains and saints. This is nearly always a mistake. Beware of presentism (judging past actors and actions through the lens of the present), and remember that the immigrants who were working in mines, employed in sweatshops, or living in urban squalor were escaping even worse living conditions in their country of origin. They came to America in unprecedented numbers to escape famine and misery. The working conditions they encountered in America were an improvement. That is why so many immigrants came here, and continued coming.

History isn’t always pretty in the making, but in America it has had a happy ending. Progress, not perfection, is the hallmark of a civilized society.

Myth #5: Courts in America Improperly Issued Injunctions Against Unions

Let’s now consider the period in American history when employers availed themselves of legal remedies for union misconduct, such as engaging in violence, forcibly interfering with the employers’ business, and preventing willing workers from performing services during a strike. Before federal labor law was passed in 1935 (the National Labor Relations Act, sometimes referred to as the Wagner Act), drastically altering the legal landscape, state law governed the employment relationship (and in many cases regulated conduct deemed to constitute common law “restraints on trade”). Employers could and did file lawsuits against unions when they violated other people’s rights, and sometimes employers obtained injunctive relief against union conduct—judicial orders forbidding certain conduct. This came to be called “government by injunction,” which the Democratic Party platform opposed as early as 1896. After an abortive effort at reform in 1914, union pressure ultimately led to the enactment of federal legislation in 1932 forbidding federal courts to issue injunctions in labor disputes in most cases. [13]

Proponents claim that this 1932 legislation, called the Norris-LaGuardia Act, was necessary to prevent the issuance of abusive injunctions restricting peaceful union activities. Critics view the law differently—the first step down the road to granting legal privileges to unions and abrogating employers’ longstanding legal rights.

Felix Frankfurter, a liberal Harvard Law School professor who later sat on the U.S. Supreme Court (appointed by FDR), reportedly wrote the Norris-LaGuardia Act. Frankfurter, an ardent New Dealer, and one of his former students at Harvard Law, Nathan Greene, had written an influential book in 1930 entitled The Labor Injunction contending that federal courts granted such injunctions with excessive zeal. Unions had long sought immunity from federal court injunctions, and in 1932 they finally obtained it. [14] The claim that federal courts were one-sided in issuing injunctions—and that peaceful picketing was routinely enjoined–has been accepted as gospel, and the Norris-LaGuardia Act is now regarded (along with the Wagner Act) as part of the “Magna Carta of organized labor.” But was the era of “government by injunction” myth or fact?

The late Professor Sylvester Petro, who taught labor law at NYU and Wake Forest for decades (and whom I profiled in Misrule of Law), argued that it is a myth. He did this in his book The Labor Policy of the Free Society (1957) and in much greater detail in a series of law review articles published in the Wake Forest Law Review and North Carolina Law Review from 1978-1982. Petro meticulously reviewed every reported state and federal court labor-injunction case during the period 1880 to 1932—numbering 524–(as well as 145 unreported labor cases) to determine if the courts acted in accordance with traditional principles of equity. Petro concluded, based on his exhaustive research, that, on the whole, courts faithfully followed the well-established common law rules and relevant procedure. Rather than finding class bias in favor of employers, Petro found that courts most often ruled in favor of non-union workers wishing to accept employment on terms that union employees had refused—that is, the courts protected the right of “scabs” to work during a strike.

Specifically, Petro concluded that “not one primary strike for better terms and conditions of employment was ever finally enjoined merely as such.” [15] The same is true for peaceful primary picketing and other forms of “strictly peaceable persuasion”: courts only granted relief when such conduct was intertwined with violence. Petro writes:

Like the other crusaders, Messrs. Frankfurter and Greene in The Labor Injunction were very quiet about the principal feature of the labor-disputes brought before the courts of equity between 1880 and 1932. Violence, vandalism, property destruction, and intimidation dominated the cases. A discussion of the labor-injunction cases which ignored that fact amounted to staging the play Hamlet without the character which gave it meaning. When forced to recognize this, the crusaders typically blamed employers either for the violence itself or for bringing it on. But the facts of the hundreds of violence cases collected here are clearly to the contrary. The aggressors were the unions and the organized workers; the victims were mainly and directly nonunion, anti-union, or rival-union employees, and secondarily the investors in the businesses which violent unionists so frequently besieged, bombed, and vandalized. (Emphasis added.) [16]

Petro concludes:

Those unaware of the pervasive violence in the cases cannot properly understand let alone appraise the rulings of the much maligned judges in the age of “government by injunction.” …[H]ad the unionists pursued their objectives peacefully and lawfully there would have been no “government by injunction.” [17]

In short, Petro believes that the judges who administered equity in labor-disputes between 1880 and 1932 “ranked high among the most faithful and gallant public servants that the United States has ever had.” [18] And yet in the mythology of American labor history they have been reviled as despicable tyrants and bullies.

Unlike merchants and manufacturers subject to the antitrust laws, whose collusion violates the law, peaceful wage-fixing by labor cartels in the guise of “collective bargaining” and other concerted activity has never been proscribed (at least not since Commonwealth v. Hunt in 1842). [19] Labor unions complain about employers’ legal abuses, but themselves enjoy remarkable privileges under federal law. [20]

Myth #6: The Model of Collective Bargaining Used in the Wagner Act Is Beyond Reproach

The Great Depression wrought the New Deal, and FDR’s Brain Trust engaged in a number of bold experiments, including the Wagner Act passed in 1935. The New Deal is now often regarded as inevitable and visionary, but in reality it was haphazard and messy. Some of it, such as the central economic controls represented in the National Industrial Recovery Act of 1933 (NIRA) and the Agricultural Adjustment Act of 1933 (AAA), both of which were declared unconstitutional, was plainly borrowed from Mussolini’s corporatism. We tend to view our current model of “collective bargaining” as pre-ordained, consistent with other nations’ practices, and beyond reproach, yet it rests on some unique and highly-controversial features.

One of the unique features of the Wagner Act (or NLRA) is the concept of “exclusive representation,” set forth in section 9(a). [21] Exclusive representation, which had never previously been adopted anywhere in the world, allows a labor union to act as the bargaining representative for all employees in a unit that selected the union by majority rule. (Unlike political elections, representation elections do not have a finite term; union representation, once selected, can last for decades without any further expression of employee support.) In other words, if the shipping and receiving department of ABC Company has 100 employees, and a 51-person majority of the employees voting in a union election favored union representation, the union would become the exclusive spokesperson for all 100 employees, even the 49 of them who opposed unionization. “Exclusive representation” forbids the employer from having any separate “negotiations” with those employees as individuals. [22] The minority of employees in the unit are effectively stripped of their individual bargaining rights for the duration of their employment. They can’t ask the employer for a raise, or a promotion, or a bonus. They must accept the terms and conditions of employment negotiated on their behalf by the union—even if they could have demanded more favorable terms on their own.

An alternative model would make employers’ recognition of unions voluntary, or allow employees who wish to be represented by a union to do so, while not forcing co-workers to go along with the majority. The “majority rule” model, necessary in the operation of government (with its fictitious “social contract”), is not essential in the workplace (particularly when union representation, once selected, has a potentially unlimited duration). Employment is not “the state.” Former Harvard President Derek Bok, who was also a labor law scholar, wrote an article in the Harvard Law Review in which he noted the uniqueness of “exclusive representation” in the United States. [23] One significant consequence of “exclusive representation” is that it forces the minority to accept the terms negotiated by the union, which unions call being a “free rider” but more accurately amounts to being a “forced rider.” Unions cite the “free rider” phenomenon as a reason to be able to force the minority to join the union or pay the equivalent of union dues (called “agency fees”) as a condition of employment, but if union representation were voluntary, there would be no “free riders.”

The “free rider” issue, and attendant controversies over union elections, the “duty of fair representation,” [24] mandatory union membership, and the payment of dues (or equivalent fees), has led to considerable litigation before the National Labor Relations Board and in the U.S. Supreme Court, and the passage of so-called “right to work” legislation at the state level. In the public sector, the “free rider” issue produced 41 years of controversy over the First Amendment rights of agency-fee payors, which was finally resolved in 2018 in the case Janus v. AFSCME. All because of the concept of “exclusive representation,” derived from the ill-fated National Industrial Recovery Act’s “codes of fair competition,” and itself a vestige of Mussolini-era labor cartels. [25]

Myth #7: Government Employees Should Be Allowed to Unionize Also

The final myth is the most outlandish of all.

Collective bargaining was not legally required in the U.S. until the NLRA in 1935, and even then it was limited to private sector employees. Recall that the rationale for unions was to rectify the supposed “inequality of bargaining power” between employees and corporate employers—to level the playing field for capital and labor. Unions seek to obtain a “fair share” of the employer’s profits through labor negotiations. At the time, even New Deal liberals, such as President Franklin D. Roosevelt, viewed government employees as a fundamentally different situation. Government employees were thought to be “public servants,” not part of an economic struggle. The New Dealers were right. The government represents the citizenry, not investors. The government does not generate a profit. The amount of compensation paid to government workers is a political decision, not the product of economic competition. In a democracy, we elect representatives to allocate finite taxpayer resources among various needs: public safety, roads, education, parks, etc. Paying taxes is not optional. FDR and other New Dealers rightly thought that the right to strike was totally incompatible with government employment: “unthinkable and intolerable,” in FDR’s words. Public sector unionization is indefensible. It is rent-seeking, and nothing more. [26]

That was then. Even though the NLRA did not cover public employees—and still does not—beginning in the 1960s, [27] the growing number of government employees at the state and local level lobbied for and obtained collective-bargaining rights, and in some cases the right to strike. Because unionization in the private sector is constrained by economic competition among employers and even among different countries (witness the collapse of the U.S. automobile industry in the face of foreign competition, especially from Japan), employers have an economic incentive to resist union organization. Notwithstanding the one-sided rules governing representation elections—favoring unions–the global economy has steadily reduced the portion of the private sector workforce in the U.S. that is represented by a union. In contrast, the public sector faces no such constraint because government has a monopoly and taxes are compulsory. Government employers have no economic incentive to resist union organizing, and sometimes even encourage it. Labor costs are simply passed through to taxpayers. Taxpayers have no choice whether to pay. “Consumers” of government services at the state or local level have no marketplace alternatives other than moving elsewhere. The public is terribly vulnerable to strikes by government employees.

As one might expect, for all the foregoing reasons the rate of union membership in the public sector has steadily grown. Government employees now account for about half of the total union membership nationwide. Public employee unions undermine democracy by using union dues to help elect candidates to state and local office who will be sympathetic to their demands. These candidates, once elected, sit across the bargaining table from the unions who got them elected. The “negotiations” are a farce. The unions write their own ticket, with the taxpayers–having no one representing their interests—footing the bill. The result is inflated government payrolls, excessive salaries, and public employee pension benefits so generous—bordering on plunder–that many state and local governments are deeply in debt.

It is now taken for granted that government workers—teachers, police officers, firefighters, and the rest—should have the same “rights” as their private sector counterparts, without considering that the “inequality of bargaining power” has no application to public servants. FDR knew better.

In all these areas, fashionable opinion has a tendency to harden into orthodoxy. Prior to this lecture, many of you may have heard from only one perspective—the pro-union position. It is my hope that some of you may be provoked to question that orthodoxy, which sometimes borders on mythology.

Thank you.

Notes

[1] See Paul Moreno, “Organized Labor and American Labor Law: From Freedom of Association to Compulsory Unionism,” 28 Social Philosophy & Policy 22 (2008); Capitalism and the Historians (F.A. Hayek, ed. 1954). As Richard Posner explained, labor law is “founded on a policy that is the opposite of the policies of competition and economic efficiency that most economists support.” Richard A. Posner, “Some Economics of Labor Law,” 51 U. of Chi. L. Rev. 988, 990 (1984). Accordingly, “the field is unlikely to attract, as a subject for teaching and scholarship, the lawyer who is deeply committed to economic analysis; it is likely to repel him.” Id.

[2] Mark S. Pulliam, “Monopoly Union Power, Wage Competition, and the Labor Antitrust Exemption: ‘Which Side Are You On?’,” 13 Pacific Law Journal 29 (1981).

[3] OPEC stands for Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries. “American labor law is best understood as a device for facilitating…the cartelization of the labor supply by unions.” Posner, supra note 1, at 990.

[4] Id. at 991 (picketing is “an attempt to interfere, by means inherently intimidating, with contractual relationships between the picketed firm and its customers and suppliers, including new workers hired to replace the strikers”).

[5] The degree of contempt in which unionists hold strikebreakers is hard to describe. Jack London reportedly had this to say about “scabs”:

After God had finished the rattlesnake, the toad, and the vampire, he had some awful substance left with which he made a scab.

A scab is a two-legged animal with a corkscrew soul, a water brain, a combination backbone of jelly and glue.

Where others have hearts, he carries a tumor of rotten principles.

When a scab comes down the street, men turn their backs and angels weep in heaven, and the devil shuts the gates of hell to keep him out.

No man (or woman) has a right to scab so long as there is a pool of water to drown his carcass in, or a rope long enough to hang his body with.

Judas was a gentleman compared with a scab. For betraying his master, he had character enough to hang himself. A scab has not.

Esau sold his birthright for a mess of pottage.

Judas sold his Savior for thirty pieces of silver.

Benedict Arnold sold his country for a promise of a commission in the British army.

The scab sells his birthright, country, his wife, his children and his fellowmen for an unfulfilled promise from his employer.

Esau was a traitor to himself; Judas was a traitor to his God; Benedict Arnold was a traitor to his country.

A scab is a traitor to his God, his country, his family and his class.

In 1904, London also wrote an article in The Atlantic about scabs, denouncing capitalism and defending violent labor uprisings. The vilification of “scabs” is an essential element of unionist lore. Pete Seeger’s pro-union folk song, Which Side Are You On?, contains these lyrics:

Oh workers can you stand it?

Oh tell me how you can?

Will you be a lousy scab

Or will you be a man?

[6] In enacting the NLRA, Congress “found” that

The inequality of bargaining power between employees who do not possess full freedom of association or actual liberty of contract and employers who are organized in the corporate or other forms of ownership association substantially burdens and affects the flow of commerce, and tends to aggravate recurrent business depressions, by depressing wage rates and the purchasing power of wage earners in industry and by preventing the stabilization of competitive wage rates and working conditions within and between industries.

Collective bargaining and other rights guaranteed by the NLRA would “restor[e] equality of bargaining power between employers and employees.” These “findings” display a gross ignorance of basic economics. The corporate form of ownership, which simply allows shareholders to pool their capital, does not tend to depress competition in the labor market or otherwise affect wages. Unions, on the other hand, exist for this purpose.

[7] I draw here and throughout upon Howard Dickman’s magisterial Industrial Democracy in America (1987); Richard Epstein’s article, “A Common Law for Labor Relations: A Critique of the New Deal Labor Legislation,” 92 Yale Law Journal 1357 (1983); Richard Epstein, How Progressives Rewrote the Constitution (2006); Morgan O. Reynolds, Power and Privilege (1984) (which I reviewed in Reason in an essay titled “Labor’s Strong Arm”); W.H. Hutt, The Strike-Threat System (1973); Moreno, supra note 1 (a particularly useful and concise summary); and the extensive published scholarship of Sylvester Petro (including his classic book, The Labor Policy of the Free Society (1957)), Edwin Viera, Jr., and Thomas R. Haggard.

[8] A full discussion of Marx’s “labor theory of value” is beyond the scope of this lecture. To greatly summarize, Marx believed that the “value” of a manufactured product is determined by the amount of labor needed to create it. Since the market price of the product is generally more than the wages paid to the workers, Marx deduced that the workers were being shortchanged—denied the full value of their labor. Marx viewed this as class-based exploitation by capitalists. Critics have noted that this “theory” is merely a tautology, and for this and other reasons the economics profession has long rejected the value theory of labor. Yet Marx’s influence persists.

[9] Holmes, a cynic who believed in the inevitability of class struggle, was receptive to Laski’s teachings. In his dissenting opinion in Vegelahn v. Guntner, 167 Mass. 92, 44 N. E. 1077, written in 1896 while he was still on the Supreme Judicial Court of Massachusetts, Holmes stated that

One of the eternal conflicts out of which life is made up is that between the effort of every man to get the most he can for his services, and that of society, disguised under the name of capital, to get his services for the least possible return. Combination on the one side is patent and powerful. Combination on the other is the necessary and desirable counterpart if the battle is to be carried on in a fair and equal way. (Emphasis added.)

[10] 15 U.S.C. section 17 (“The labor of a human being is not a commodity or article of commerce. Nothing contained in the antitrust laws shall be construed to forbid the existence and operation of labor, agricultural, or horticultural organizations, instituted for the purposes of mutual help, and not having capital stock or conducted for profit, or to forbid or restrain individual members of such organizations from lawfully carrying out the legitimate objects thereof; nor shall such organizations, or the members thereof, be held or construed to be illegal combinations or conspiracies in restraint of trade, under the antitrust laws.”).

[11] Economic historians T.S. Ashton and W.H. Hutt explain this in their respective works. See T.A. Ashton, “The Standard of Life of the Workers in England, 1790-1830,” in Capitalism and the Historians, supra note 1, at 123; W.H. Hutt, “The Factory System of the Early Nineteenth Century,” in Capitalism and the Historians, supra note 1, at 156; T.S. Ashton, The Industrial Revolution, 1760-1830 (1948).

[12] See W. S. Woytinsky, “Long-Range Trend in Per Capita Income and Wages,” Social Security Administration Bulletin (December 1942); U.S. Bureau of the Census, Historical Statistics, Series D. Other common measures of “oppression,” such as the average number of hours worked per week, average wages, and life expectancy, continued to steadily improve in the early 20th century, before the passage of New Deal legislation. Richard Epstein, How Progressives Rewrote the Constitution 5-7 (2006).

[13] To briefly summarize, in the late 19th century employers had learned to combat labor violence and disruptive tactics (such as secondary boycotts) by seeking injunctions against unions under common law rules forbidding conspiracies and restraints of trade. After the Sherman Act was enacted in 1890, unions were also subject to the federal antitrust laws, and were sometimes enjoined on that basis. Radical union leader Eugene Debs was jailed for violating such an injunction during the Pullman strike in 1894. When the Supreme Court explicitly applied the antitrust laws to unions in 1908 (Loewe v. Lawlor), organized labor successfully lobbied for passage of an antitrust exemption in the 1914 Clayton Act, but unions remained subject to injunction for violations of state law. Moreover, in Duplex Printing Co. v. Deering (1921), the Supreme Court ruled that the Clayton Act did not protect secondary activity. The goal of the Norris-LaGuardia Act was to prevent federal courts from issuing injunctions against labor unions for any reason—effectively granting them a legal privilege. See Moreno, supra note 1, at 31-40; Pulliam, supra note 2, at 39-43.

[14] The Labor Injunction was tendentious enough to be called a “brief for the Norris-LaGuardia Act,” yet is now cited reverentially by pro-labor scholars. Moreno, supra note 1, at 24.

[15] Sylvester Petro, “Injunctions and Labor Disputes: 1880-1932 Part I: What the Courts Actually Did—And Why,” 14 Wake Forest Law Review 341, 345 (1978).

[16] Id.

[17] Id. at 345-46.

[18] Id. at 346. Professor Richard Epstein concludes that

In my view Petro has much the better of the historical argument. The chief flaw of the Frankfurter and Greene study is, as Petro points out, that it never asks the question of whether the issuance of the labor injunction was a use or an abuse of power. Where there is the threat of force by workers, it is the failure to grant the injunction that is the abuse of discretion, not its issuance. And as Petro rightly points out, the application of the injunction to labor cases did not involve any departure from the well established equitable principle that injunctions are an appropriate response to threats of irreparable harm.

Epstein, supra note 7, 92 Yale L.J. at 1407 n. 149 (emphasis added; citations omitted).

[19] 45 Mass. 111 (1842).

[20] See Moreno, supra note 1, at 40-52; Morgan Reynolds, supra note 7, at 263-66; Pulliam, supra note 2, at 42, 55-57.

[21] 29 U.S.C. section 159(a).

[22] J.I. Case Co. v. NLRB, 321 U.S. 332, 334-36 (1944). Here is how the Court approvingly described the collectivist goal of the NLRA: “The very purpose of providing by statute for the collective agreement is to supersede the terms of separate agreements of employees with terms which reflect the strength and bargaining power and serve the welfare of the group…. The practice and philosophy of collective bargaining looks [sic] with suspicion on…individual advantages.” Id. at 338 (emphasis added).

[23] Derek Bok, “Reflections on the Distinctive Character of American Labor Laws,” 84 Harvard Law Review 1394, 1397 (1971). Many other industrialized nations, mainly in Europe, conduct labor relations through “works councils,” multi-employer associations, or on an industry-wide basis, or regulate labor conditions by centralized government mandate.

[24] The “duty of fair representation” is a judge-made doctrine, found nowhere in the Wager Act itself, that was concocted by the Supreme Court to combat rampant union racial discrimination in the railroad industry. See Benjamin Aaron, “The Union’s Duty of Fair Representation under the Railway Labor and National Labor Relations Acts,” 34 J. Air L. & Com. 167 (1968)

[25] Moreno, supra note 1, at 41-43; Sylvester Petro, “Civil Liberty, Syndicalism, and the NLRA,” 5 U. of Toledo L. Rev. 447 (1974).

[26] The literature on this point is vast. See, e.g., Daniel DiSalvo, “The Trouble with Public Sector Unions,” National Affairs (Fall 2010) 3-19; Robert S. Summers, Collective Bargaining and Public Benefit Conferral: A Jurisprudential Critique (1976); Sylvester Petro, “Sovereignty and Compulsory Public-Sector Bargaining,” 10 Wake Forest L. Rev. 25 (1974); Mark S. Pulliam, “Legal Aspects of Exclusive Representation: Ruminations on the Private-Public Sector Analogy,” 5 J. of Labor Research 351 (1984).

[27] As the Supreme Court noted in Janus v. AFSCME (2018):

The first State to permit collective bargaining by government employees was Wisconsin in 1959, and public-sector union membership remained relatively low until a “spurt” in the late 1960’s and early 1970’s, shortly before Abood was decided [in 1977]. Since then, public-sector union membership has come to surpass private-sector union membership, even though there are nearly four times as many total private-sector employees as public-sector employees. (Citations omitted.)