The Importance of Curiosity

Why Eden’s fatal sin is a necessary virtue in this mortal coil.

This essay first appeared in Law & Liberty, on April 26, 2021 (here). Thanks to Real Clear Policy and Real Clear Books!

Curiosity was once thought to be, in the words of English historian G.M. Trevelyan, “the life blood of real civilization.” Frank Buckley laments that “there’s less curiosity today than in the past,” and has written a new book, Curiosity and Its Twelve Rules for Life, in an attempt to rectify the dearth. If this mission seems far afield for a legal academic, Buckley defies the conventional stereotype of a law professor. In addition to his considerable body of scholarly work, Buckley is a senior editor of The American Spectator, a columnist for the New York Post, and served as an advocate of and occasional speech writer for the President that many academics love to hate, Donald Trump.

In light of his demonstrated curiosity regarding a host of different subjects, Buckley’s foray into curiosity is not surprising. He is a prolific author and versatile scholar. While teaching at George Mason University’s Antonin Scalia Law School (since 1989), Buckley has written numerous legal articles and books on a variety of topics (including a couple that I reviewed for Law & Liberty and elsewhere), ranging from a technical critique of the American legal system to a rumination on the possibility of secession. Truly eclectic, Buckley was educated (and holds dual citizenship) in Canada and the U.S., helped run the law and economics program at George Mason for over a decade, and has taught at the Sorbonne.

His wide-ranging interests are on display in Curiosity and Its Twelve Rules for Life, which sounds like a self-help book but isn’t. In fact, Buckley makes it clear at the outset that his book is not “Jordan Peterson’s twelve rules for life. Those were guidelines on how to survive and surmount the challenges of life in a bleak and cold climate.” Buckley explains that his twelve rules of curiosity, in contrast, “are meant for the more spirited and fun-loving people I met when I moved from Canada to the United States.” His book is not really a “rule book” at all. The first “rule” he discusses is “Don’t make rules.”

So, what exactly is the point of the book? After a year of pandemic-induced isolation, and in the wake of four years of escalating (and increasingly toxic) obsession with partisan politics, Buckley wants us all to look beyond headlines, turmoil, and social media messaging to savor the “world of wonders” available for our “enjoyment and delight,” if we simply open our eyes and allow our imaginations to explore them. As a well-read and cultured (self-described) boomer, and with a younger audience in mind, Buckley serves as a tour guide into the world of wonder beckoning to the curious.

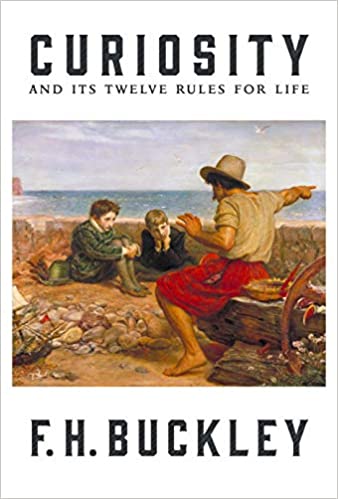

Buckley takes the reader on a whirlwind (and necessarily abbreviated) survey of subjects that are not the conventional fare in undergraduate education or popular media. The tour begins with the cover art, which features The Boyhood of Raleigh (1870) by John Everett Millais. Buckley has an interest in art history, and punctuates his narrative with vignettes about Gothic architecture, Pre-Raphaelite painters, Hieronymus Bosch, and Aubrey Beardsley. Buckley also has a fascination for Blaise Pascal, whom he describes as one of the “greatest thinkers of all time.” Pascal’s name pops up in almost every chapter, along with—less frequently–Ludwig Wittgenstein, Immanuel Kant, Aristotle, John Stuart Mill, and other philosophers.

But the book isn’t a dry tract on philosophy—or art history. Buckley tells stories about the philosophers, including a recurring theme of Pascal’s defense of an austere Catholic sect called the Jansenites against the powerful Jesuits. Sometimes accused of being an Anglophile due to his affection for the Parliamentary form of government, in Curiosity Buckley displays an appreciation of 20th century French intellectuals, especially the existentialist Albert Camus, who was influenced by Pascal. Buckley admires Camus, despite his lack of religious faith, because of Camus’s courage in breaking with collaborators during the Nazi occupation of France during World War II, and in rejecting the fashionable communism of his fellow intellectuals (such as Jean-Paul Sartre) after the war. Buckley manages to make the anecdotes interesting, not inside baseball. Curiosity is an old-fashioned liberal arts education in a nutshell—humanities for the novice.

Curiosity is structured as a series of life lessons (take risks, court uncertainties, be original, show grit, be creative, don’t be smug, etc.) illustrated with examples drawn from Greek mythology, the Bible, Catholic theology, Hebrew culture, literature, movies, comedy, history (European, Canadian, and American), and music. Buckley’s erudite treatment of these subjects is vaguely reminiscent of William Bennett’s virtue-building primers from the 1990s, albeit for a more sophisticated college-age (or older) audience–fatherly advice for a happy and fulfilling adulthood.

Owing to Buckley’s broad range of knowledge, there is something for everyone. A thumbnail sketch of law and economics pioneer Henry Manne, a nod to Oliver Wendell Holmes, and some Harvard Law School stories for legal readers; references to Frank Knight, the Austrian School, and John Maynard Keynes for practitioners of the dismal science; Thomas Aquinas, St. Augustine, John Henry Newman, and Thomas a Kempis for Christians; and plenty of recognizable pop culture figures for the philistines among us. The book is not without an occasional political aside, either.

How did we become so incurious? Buckley contends that “We’ve placed all our chips on harsh ideologies that, by purporting to explain everything, teach us to ignore inconvenient counterexamples…. Curiosity, which used to be a liberal virtue, is increasingly a conservative one, as progressives bury themselves in a distorted universe of risk-free lives, intersectional victims, and cartoon-like villains.” Buckley explains:

On the extremes, Trump-haters and Trump-lovers shriek past each other, like furious apes locked in a cage. But it’s mostly the rage-filled progressives who are to blame. In 2020, they made curiosity about anything other than Black Lives Matter or the pandemic seem sinful. They’ve tried to banish risk and fault the risk-taker for his negligence or toxic masculinity. They’ve descended into incurious ideologies and bitter partisanships that permit them to ignore the harms imposed on others…. But it cannot last. However worthy you might think the progressives’ causes, they’ll bore you in time, unless you are wholly without a spark of curiosity.

Buckley also has something to say about the state of higher education:

No one should be more curious than the young, but they’ve been betrayed by America’s colleges, which is where curiosity goes to die. Curious people need the freedom to experiment with new ideas, as one might try on new ties before a mirror. That’s not going to happen if the woke police stand ready to pounce on any deviation from their radical orthodoxy. Victimhood has been weaponized and turned into a tool of oppression by the flint-eyed progressives on campus and their enablers on college administrative staff.

Buckley is a deft writer, and his prose is vivid and sprightly. For example, he avers that “viewers of CNN and MSNBC appear to have had the curiosity gene removed at birth, so repetitive are the politics.” Curious is often witty and always a delight to read.

At the same time, Buckley soberly reflects on a serious subject that curious people should not be afraid to confront—the prospect of their own mortality. He states that “the loss of religious awe and a transcendent vision of life and death has resulted in a banal culture of minimalist concerns and politicized art and literature. Great art is made by people who are curious about what happens when life ends or of the sense to be made of life if they think nothing does.”

Buckley devotes the closing chapters of the book to his final “rule”—one that aging boomers will soon encounter: Realize you’re knocking on heaven’s door:

We’ve seen Facebook accounts go dark and old friends…go the way of all flesh, and we’re beginning to realize that the same thing will happen to us. As that thought hits us, we’ll start thinking about the Four Last Things: Death, Judgment, Heaven, and Hell…. I await a curiosity about what happens upon death and a new religious awakening. And that will be my generation’s final gift to the Zeitgeist. After the sex and drugs and rock ’n’ roll, after experiencing every old vice and inventing a few new ones, only one thing remains, and that is a religious revival and a return to conventional morality.

Buckley ends the book with these poignant words:

Our culture asks us to anesthetize our curiosity about what awaits us upon death…. Even as God made Eve curious, I think the incuriosity of modernity will ultimately prove unsatisfying. We were created as curious beings and will always seek answers, especially to the most fundamental questions of our existence. And that, more than anything, is why curiosity matters.

Mortality can be a gloomy topic for reflection, but Buckley’s treatment of it ends on a hopeful note. The past year was stressful and tumultuous for many Americans. Strife, isolation, and anxiety took a toll on the human condition, causing many people to become fearful, timid, and lonely. An entire generation has been scarred by pandemic-related hysteria. Curiosity offers a tonic for the spiritual doldrums. As the ever-chipper Buckley notes, “Now, more than ever, curiosity matters. In 2020, we learned just how much our health, our happiness, our sanity, depends upon it…. There is only one way out of the madness, and that was to let our curiosity take us by the hand and lead us.”