An Elegy for the Boy Scouts

Lord Baden-Powell, who founded the venerable organization, would not recognize what it has become.

An edited version of this essay first appeared in Law & Liberty on July 27, 2021 (here). Thanks to Power Line, Instapundit (here), Real Clear Policy (here), SE Texas Record (here), The Leader Maker (here), Never Yet Melted (here), and the Intercollegiate Review (here). And thanks to the many emails I received from readers sharing my concern. I received more responses to this piece than any other I have written in recent years.

The news over the past few years has offered little to cheer about, but a recent story reporting an unprecedented 43 percent decline in membership in the Boy Scouts of America from 2019 to 2020—from 1.97 million Cub Scouts and Boy Scouts to 1.12 million–was especially dispiriting. To make matters worse, the Associated Press reports that BSA membership has fallen even further since 2020—to about 762,000. For purposes of comparison, combined enrollment in the BSA—Cub Scouts and Boy Scouts– peaked in 1972 at 6.5 million members and as recently as 1998 was 4.8 million. These numbers are shockingly grim. The once-robust BSA is on life support, with a seemingly fatal malady.

What happened to this venerable youth organization, brought to America in 1910? The BSA was once an iconic institution, producing as Eagle Scouts prominent Americans including President Gerald Ford, astronaut Neil Armstrong (the first man to walk on the moon), film maker Steven Spielberg, animator William Hanna, businessman Ross Perot, television host Mike Rowe, and many others. More than 130 million Americans have participated in the BSA since its inception. The immediate cause of the precipitous decline in membership is a triple-whammy of the Covid-19 pandemic, highly-publicized litigation involving charges of decades-old sexual abuse against 60,000 alleged victims (leading to an $850 million settlement and BSA’s Chapter 11 filing in 2020), and the aftermath of the national organization’s decision in 2019 to admit girls (resulting in the withdrawal from the program of its largest participant, the Mormon (LDS) Church, ending an association that began in 1913).

In reality, however, the baleful trends were evident much earlier. While overall membership peaked in the early 1970s, the participation rate—the percentage of age-eligible boys who were members of the BSA—began to decline a decade (or more) earlier. The effect of this decline was disguised by increases in the U.S. population and expansion of the traditional scouting program. The heyday of the BSA coincided with the demographic bubble of post-WWII births—the Boomer generation. As this cohort grew up, the attention of American youths was distracted by other cultural influences: greater affluence, competing recreational activities, the proliferation of organized youth sports, a greater incidence of two-income households (fewer stay-at-home mothers) and single-parent households due to divorce, the ubiquity of suburbia and its rich array of creature comforts, growing demographic diversity, and—in the past decade—the advent of computer games that now consume the interest of many boys.

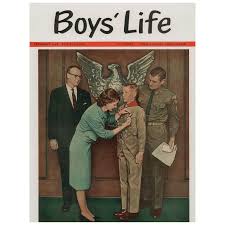

The Boy Scout Law—with its embrace of religious faith (“reverence”) and heterosexuality (“morally straight”)—faced hostile headwinds in an increasingly secular and “tolerant” society. And, to be honest, in a youth culture increasingly sensitive to what is fashionable—a norm rigidly and relentlessly enforced by social media through the omnipresent smart phone—in recent decades membership in the Boy Scouts was regarded as unacceptably “uncool.” In the 1950s and 1960s, peer pressure went in the opposite direction, reinforcing the attractiveness of scouting. Norman Rockwell’s cover illustration for the February 1965 issue of Boys’ Life depicts two parents proudly watching as their clean-cut son—standing at attention in a crisply-pressed uniform—receives his Eagle medal. Alas, times change. As the BSA’s membership began to decline, the national organization tried to remain “relevant,” adapting to America’s abrupt cultural and demographic shifts with responses that were sometimes clumsy and even counter-productive.

After decades of litigation brought by atheists and homosexuals regarding the BSA’s exclusionary membership requirements—which were upheld by the U.S. Supreme Court in the landmark case Boy Scouts of America v. Dale (2000) as the exercise of the BSA’s First Amendment rights–the BSA capitulated by allowing gay youths full participation in 2014 and allowing openly gay adults as leaders in 2015. Instead of stemming BSA’s membership decline, the national leadership’s acquiescence to atheists and homosexuals—some believe due to pressure from major corporations whose financial patronage had become indispensable to the organization’s operation—only accelerated it.

The timing of the 2014 policy change was as unfortunate as the decision itself. In late 2012, after more than a decade of costly litigation brought by the local chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union on behalf of agnostics and homosexuals against the Boy Scouts program in San Diego (then known as the Desert Pacific Council), the BSA scored a stunning legal victory. The ACLU’s lawsuit had challenged leases between the BSA and the city of San Diego on the ground that they constituted an “establishment of religion.” The leased property housed the council’s headquarters and a Youth Aquatic Center built using private funds. A unanimous Ninth Circuit panel reversed the activist ruling of federal district judge Napoleon Jones and ruled in favor of the BSA on all issues. The Ninth Circuit overruled Jones’ 2003 decision that evicted the BSA from their facility on city-owned property in Balboa Park, where the council had maintained a presence since 1918.

Instead of treating the Ninth Circuit victory—along with the 2000 decision in Dale—as confirmation that the BSA’s longstanding policies were on firm legal ground, less than six months later, the national organization voted to allow openly-homosexual youth as members. The policy change was bitterly disappointing to many BSA supporters, especially in San Diego.

With recent moves more closely resembling the actions of a Fortune 500 HR department than the paramilitary organization founded in Britain by Lord Baden-Powell in 1908, the BSA now has a Chief Diversity Officer, boasts a Diversity and Inclusion Statement, and in 2020 even proposed an Eagle-required merit badge requiring mastery of Diversity, Equity and Inclusion to achieve scouting’s highest rank. This last innovation was apparently too much for traditionalists to swallow, and the proposed merit badge has been put on hold pending further study.

In the corporate jargon of the BSA’s national leadership, “The introduction of the proposed Diversity, Equity and Inclusion merit badge is being delayed to allow for the careful consideration and evaluation of feedback received from a wide variety of commenters on the draft requirements.” The New York Times reported that “The nonprofit also joined a growing number of organizations announcing public support for racial equality and the Black Lives Matter movement.” Earlier this year, the BSA’s century-old official publication, Boys’ Life, was renamed Scout Life in order to be gender-neutral.

Many parents enrolled their children in the Cub Scouts and Boy Scouts because those programs represented old-fashioned, wholesome, traditional values—Norman Rockwell’s idealized version of Americana, pictured in numerous Boys’ Life covers and calendars during his 60-plus year association with the BSA. Much of the attraction of the BSA is that it was seen as a respite from—or even an antidote to—the hostile forces in a culture many parents regarded as a negative influence on their children. The whole point of getting youths outdoors, exploring nature, was to shield them from such influences. When the BSA got “woke,” many conservative and religious parents turned to alternative youth organizations such as Awana, Trail Life USA, Alert Cadet, and programs directly sponsored by various churches.

As the father of two Eagle Scouts, I report these developments with great sadness. I remember with fondness my youthful participation as both a Cub Scout and Boy Scout: earning advancements and merit badges, learning new skills (paddling a canoe, shooting a rifle), going camping, attending summer camp, hiking, cooking outdoors, Blue and Gold dinners, and much more. When I was in elementary school, most of the boys in my class were Cub Scouts. Is this mere nostalgia? I think not. I recall with even greater fondness my experiences with my sons’ troop as an adult leader, backpacking at Philmont Scout Ranch in New Mexico, scuba diving at the Florida Sea Base, and the “normal” assortment of summer camps, outdoor activities, and Eagle Scout projects. The scouting program helped many boys become confident, self-reliant young men. The adults benefited from the program also; I know I did.

The Boy Scouts are not alone in facing these modern challenges. The decline of membership in the BSA tracks other trends in the U.S. over the same time period: declining Catholic school enrollment, declining church attendance, declining church membership, declining private-sector union membership, declining participation in bowling leagues and civic organizations such as Rotary and Kiwanis, declining rates of marriage and child birth, declining voter turnout, and fewer family dinners. We live in an era of fragmenting community–bowling alone, shopping on Amazon, streaming movies at home, and telecommuting. Not all of these trends are related, of course, but they all reflect changes in the American culture, economy, or society. Even the Girl Scouts of the USA is facing a steep decline in membership—a fall of nearly 30 percent–from 1.4 million in 2019-2020 to about a million this year.

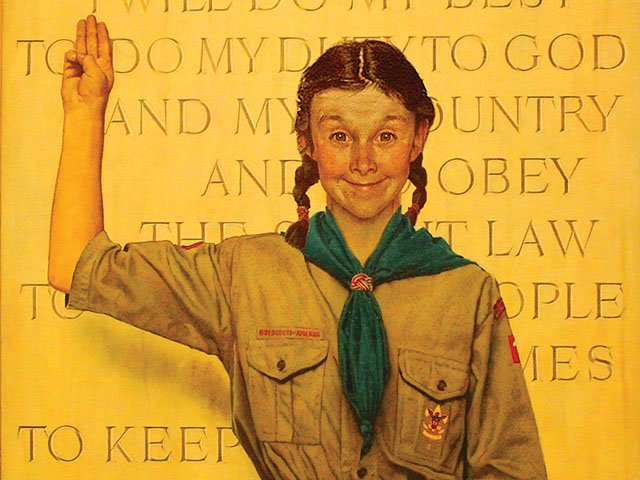

Ironically, when the BSA began to admit girls, some girls abandoned the Girl Scouts to participate in the more outdoors-oriented program that had once attracted boys. The Girl Scouts objected to what they viewed as “poaching” by the BSA—recruiting girls as members. The recruiting worked. Some Girl Scouts wanted to do more than sell cookies. From my own—admittedly anecdotal—experience, when I moved from Texas in 2019, I called the local Boy Scouts council to find a troop to whom I could donate a large quantity of camping gear I had accumulated during my sons’ involvement in scouting. The council identified a recently-formed troop interested in the gear, which turned out to be an all-girls unit. An Independence Day parade I attended this year in Greenback, Tennessee featured a float by a local BSA troop that was a group of girls. The organization created by Lord Baden-Powell to instill “masculine” skills and habits in Britain’s urban youth now has greater allure to girls than boys!

Change is inevitable, of course, but what does the impending demise of the BSA portend? Is scouting merely a cultural relic of the 20th century, the obsolescence of which is no more consequential than the disappearance of drive-in movie theatres, Roy Rogers lunch boxes, transistor radios, or poodle skirts? Or does the BSA represent a canary on our cultural coal mine—a warning sign of a mortal threat to our collective wellbeing that we ignore at our peril? The Boy Scout Oath serves as a shorthand for the American creed: “On my honor I will do my best to do my duty to God and my country and to obey the Scout Law; to help other people at all times; to keep myself physically strong, mentally awake, and morally straight.”

If the belief system underlying the BSA—by which I mean the pre-woke conception of scouting—has fallen out of favor, Americans have cause to be very concerned. Personal excellence (“doing my best”), devotion to God and country, individual responsibility, and commitment to bourgeois values (trustworthy, kind, thrifty, brave, etc.) are traits essential to the preservation of civil society. Nihilism, narcissism, and hedonism are not sound foundations for a stable community. The failing health of the Boy Scouts is attributable to many factors, but clearly represents what Bowling Alone author Robert Putnam calls a “decline of social capital.” But it is more than that. Lord Baden-Powell did not write Scouting for Boys in 1908—the foundational text for the worldwide scouting movement–to increase social capital, but to improve the character of Britain’s male youth, which he found wanting.

Baden-Powell, a career military officer in imperial Britain and a hero of the Second Boer War (1899-1902), became concerned that British youth were succumbing to the vices of an industrial and urban society: passivity, sloth, smoking, drinking, poor hygiene, and a general decline in what he felt were essential masculine qualities. So, he began the scouting program to “save boys from the ills of modern life.” A century later, Baden-Powell’s concerns are as vital as ever.

Baden-Powell felt that learning outdoor skills would make boys “strong and plucky,” and that self-reliance was essential to character building. Thus, his fascination for knot-tying, navigation, fire-building, camping, cooking, first aid, physical fitness, and surviving the wilderness—practical, quasi-military skills that are still a staple of the scouting program. All of this was in aid of improving boys’ character—making them productive citizens. Some of Baden-Powell’s concepts seem dated more than a century later, but many of them are timeless, including the motto he coined: Be prepared. The games, skits, songs, campfire yarns, and patrol activities he promoted were techniques designed to accomplish the ultimate goal of self-improvement.

Baden-Powell’s mission was to turn boys into patriotic, devout men. Near the end of Scouting for Boys, Baden-Powell exhorted his charges:

Your forefathers worked hard, fought hard, and died hard, to make your country for you. Don’t let them look down from heaven and see you loafing about with your hands in your pockets, doing nothing to keep it up.

He added: “Don’t be disgraced like the young Romans, who lost the Empire of their forefathers by being wishy-washy slackers without any go or patriotism in them.” In a culture that demonizes “toxic masculinity,” treats gender as a “fluid” construct rather than a biological fact, medicates boys to address their boisterous behavior, and encourages androgynous role models, we need more character building for boys, not less.

Playing video games with an Xbox or PlayStation is no substitute for learning outdoor skills. Call of Duty or Fortnite will not teach boys the qualities they need to become young men and productive citizens. Without compulsory military service, the only exposure many boys will have to discipline, teamwork, male authority figures, and the reinforcement of positive masculine traits, such as honor, courage, determination, chivalry, and self-reliance will be through participation in competitive sports, strong families, and programs like scouting. (Even America’s service academies are no longer reliable instructors of these virtues.) The Boy Scouts used to take seriously its stated mission: preparing young men (now “people”) to make ethical and moral choices over their lifetimes by instilling in them the values of the Scout Oath and Law. This is a critically important project that no other institution in America seeks to undertake.

The Boy Scouts have wandered far off course and lost sight of Lord Baden-Powell’s mission, possibly squandering his legacy—and that of the BSA—in the process.