The “Shadow Docket”: Sour Grapes or Sinister Plot?

The once-adored Supreme Court faces the Righteous Brothers’ romantic plight: “And now you’re starting to criticize little things I do.”

This essay originally appeared in Law & Liberty on February 21, 2023 as “Legal Progressives Have Lost That Lovin’ Feelin'” (here). Thanks to Power Line, How Appealing, Instapundit (here), Legal Insurrection (here), Real Clear Books (here), Real Clear Policy (here and here), Real Clear Wire (here), and National Review (here)!

Liberal law professors used to love the U.S. Supreme Court. For half a century, they applauded activist decisions, proposed new theories of “noninterpretive” jurisprudence, and blew kisses to the Justices most responsible for steering the Court to the left—e.g., Earl Warren, William Brennan, William O. Douglas, and Ruth Bader Ginsburg. In books such as Gideon’s Trumpet (1964), novel Warren Court decisions extending unprecedented procedural rights to criminal defendants were hailed as exemplars of wisdom and enlightenment. In a prior era, the job of “Supreme Court correspondent” for newspapers such as the New York Times and the Washington Post consisted of enthusiastic fandom–applauding every doctrinal innovation advanced by the liberal majority on the Court. This seductively-powerful flattery was dubbed the “Greenhouse Effect.”

Then, abruptly, the Left’s devotion to the Court turned sour. Seemingly overnight, liberals spurned the Court, reminding observers of the song You Lost That Lovin’ Feelin’. After decades of devotion, progressives have lost their “lovin’ feelin’” for the Court. As the song goes, “Now it’s gone, gone, gone.” In contrast with their previous ardor, liberal Democrats are questioning the legitimacy of the Court and proposing court-packing schemes, term limits for Justices, and other measures that were once the province of conservative critics of judicial activism—measures that liberals formerly condemned as “threatening the independence of the judiciary.” What happened? Stated succinctly, the “rule of five”—Justice Brennan’s cynical shorthand for the number of votes needed to form a majority—has turned against progressives accustomed to having their way. To their considerable chagrin, President Donald Trump flipped the Court.

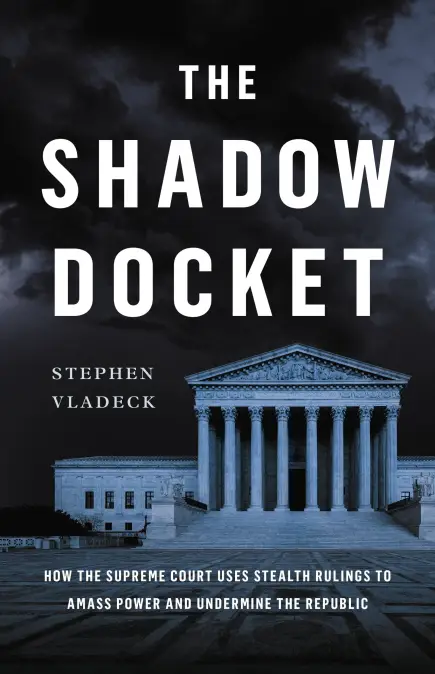

With the addition of Trump-appointed Justices Gorsuch, Kavanaugh, and Barrett, the Court’s long-suffering conservative minority is now in charge. When brazenly-activist lower court judges abused their authority by issuing nationwide injunctions in cases challenging President Trump’s immigration policy and other matters, the new conservative majority sometimes had to issue orders vacating such erroneous rulings–to the dismay of Trump’s vociferous opponents. The reversal of Roe v. Wade in Dobbs last year removed all doubt that the tide has finally turned on the Supreme Court—and not coincidentally so has the tenor of scholarship from the legal academy. Like a jilted lover, the left-wing professoriate holds the Court in scornful contempt. University of Texas law professor (and CNN analyst) Stephen Vladeck’s The Shadow Docket is a prime example.

Beginning with the book’s opening sentence, Vladeck complains about the Court’s reversal of precedents he holds dear (i.e., Roe v. Wade). His book, however, does not simply whine about the Court losing its liberal majority; Vladeck contends that something much more ominous is afoot. The book’s overwrought subtitle is How the Supreme Court Uses Stealth Rulings to Amass Power and Undermine the Republic. The target of Vladeck’s misguided attack is the Court’s use of unsigned orders (as opposed to formal decisions) to manage its docket. This longstanding practice is both necessary and unremarkable.

The “shadow docket” is an epithet sometimes used to refer to the Court’s disposition of procedural matters such as case scheduling, granting and vacating stays, ruling on so-called “emergency motions,” issuing injunctions, and even whether to hear a particular case on the merits. Such procedural dispositions are typically issued via “orders” without extensive briefing or oral argument, often do not set forth the reasoning behind the decision, and do not indicate the number or identity of Justices who voted in favor of the order. To the Court’s new-found critics, the “shadow docket” is a nefarious, secretive process rife with abuse. But is the objection well-taken, or simply sour grapes over the Court’s recent personnel shift?

The reality is, the Court has long conducted its business primarily through unsigned orders. Indeed, Vladeck conceded in his 2021 testimony before the Senate Judiciary Committee, from which his book draws, that “the shadow docket has been around for as long as the Supreme Court.” In fact, the most important decisions the Court makes—which cases to decide on the merits—are handled in this manner. Only recently has the longstanding reliance on unsigned orders to manage the Court’s docket been called into question with the unsavory sobriquet “shadow docket.”

In a typical year, the Court—whose jurisdiction is, with a few exceptions, discretionary—receives between 7-8,000 petitions for certiorari (requests for review), and “grants cert.” in only about 80, or about one percent. The rest are summarily rejected, without oral argument or an explanation of reasons. (Many of the Justices participate in a “cert. pool” to review cert. petitions, meaning that the Justices rely on a memo written by one of the Justices’ law clerks to decide which cases to hear, rather than read the briefs themselves.) In other words, 99 percent of litigants seeking relief from the Supreme Court receive an unsigned order denying review, with no further explanation. Vladeck doesn’t dispute these numbers.

There is simply no way nine Justices and their staffs could consider all 7-8,000 appeals on the merits. Keep in mind that the number of cases briefed, argued, and decided in the Supreme Court each year, with a full (and often lengthy) written decision, is generally between 60 and 80.

While some observers believe that the Court could (and in prior years did) handle a greater number of cases each term, it would be impracticable for the Court to decide more than, say, 150-175 cases a year—two or three percent of the cert. petitions. So, regardless of its current workload, the Court’s past practice (ultimately limited by finite judicial resources) requires that an overwhelming majority of matters be disposed of summarily. And so they are. Characterizing this process as “stealth rulings” that “undermine the republic” is absurd hyperbole. Focusing on the day of the week and time of day (or night) orders in emergency matters are issued ignores the urgency with which the Court’s personnel act.

Due to its status as the nation’s court of last resort, litigants tend to bombard the Supreme Court with procedural requests in high stakes cases, including requesting the issuance of “emergency” stays of unfavorable lower court decisions. Rulings on such requests are handled in the same manner as the Court’s decision whether to grant cert., i.e., by unsigned order. The only difference is that the decision on such “emergency” requests is made in an expedited manner.

Vladeck is particularly exercised by the fact that at “two minutes before midnight” on September 1, 2021—nearly 10 months before the Dobbs decision was issued on June 24, 2022–the Court declined to grant emergency relief to block a Texas law, Senate Bill 8, that banned abortions past the sixth week of pregnancy, even though the law appeared to be contrary to Roe v. Wade. The Court’s decision not to enjoin the enforcement of a state law (without ruling on the constitutionality of the law) was in the form of an unsigned order to which three Justices dissented. This is an example, Vladeck contends, of the Court’s abuse of the “shadow docket.” Vladeck doth protest too much. The Texas Heartbeat Act had just taken effect and was the subject of numerous lawsuits in state and federal courts.

More importantly, the Supreme Court had already granted cert in Dobbs, on May 17, 2021, and by the time that the application to enjoin the Texas law was filed, the briefing in Dobbs was substantially completed. Dobbs was argued on December 1, 2021. In other words, the Court already had a major abortion case on its “merits” docket and declined to intervene in another case that had not yet been fully litigated. The Court’s actions were wholly warranted. The Court eventually heard expedited argument in the Texas case (Whole Woman’s Health v. Jackson) two months after the “cryptic” order was issued, and about a month later produced a complicated, 42-page decision that did not address the constitutionality of the Texas law.

Dobbs ultimately overruled Roe v. Wade, which is the real source of Vladeck’s ire. He risibly attempts to use the Court’s denial of premature emergency relief in the Texas case to excoriate the Court for imagined skullduggery. The elaborate procedural history of Whole Woman’s Health v. Jackson was due entirely to the unorthodox nature of Senate Bill 8, which directs enforcement exclusively through private civil actions rather than by government officials. Vladeck’s misplaced criticism of the Court suffers from the same defect as Justice Sotomayor’s dissent in Whole Woman’s Health v. Jackson, which Justice Gorsuch (the author of the majority decision) stated “bears no relation to reality.”

Like many of his progressive colleagues in the legal academy, Vladeck admittedly favors a left-of-center policy agenda on a variety of subjects (abortion, the death penalty, immigration, religious liberties, environmental law, election integrity, COVID restrictions, etc.), which frequently puts him “radically” at odds with the rulings of the Court’s conservative majority. He implicitly acknowledges that disagreement over results forms the basis of arguments against the “shadow docket” by asserting that the Court’s orders have “become far more publicly divisive in recent years.” Eliciting a dissent from the Court’s liberal Justices (sometimes joined by Chief Justice Roberts) doesn’t make an order “sharply partisan.”

Disagreement on the Court is common, and it is just as likely that the dissenters overstate their case in an effort to “work the refs” in legal academia. In the case of Vladeck, the trick worked. If the Court’s orders suited the professoriate, as they did in the past, there would likely be no phony claims of “stealth rulings” that “undermine the republic.”

Now, however, Vladeck rails against rulings he disagrees with as “partisan decisions” that are “flying under the radar.” Oddly, keeping track of the Court’s “stealthy,” under-the-radar “shadow docket” has become a cottage industry for law professors and left-wing groups such as the Brennan Center. Is it plausible to describe as “inscrutable,” “obscure,” and “inaccessible” a process that has been examined at length in law review articles, congressional testimony, and (now) books?

When Vladeck warns that “the rise of the shadow docket, especially at the expense of the merits docket, has negative effects on public perception of the Court — and of the perceived legitimacy of the Justices’ work,” one suspects that he is weeping crocodile tears. Unlike Vladeck’s shrill commentary for Slate and MSNBC, The Shadow Docket is, thankfully, not entirely a screed against the new conservative majority on the Court; it also contains a workmanlike account of the “rise of certiorari,” beginning with the Judges’ Bill in 1925, and Supreme Court practice and procedures in general. In the course of that overview, Vladeck acknowledges that “modern” constitutional law began in 1937, when the Court “fundamentally reconceived its role in enforcing the Constitution against state and federal government actors.”

Congress’s granting the Court enormous discretion in its case selection (through certiorari) coincided with the rise of an activist judiciary, although liberal law professors uttered not a peep of complaint about the “shadow docket” until the recent advent of a conservative majority on the Court. In fact, Vladeck persuasively (and approvingly) suggests that the Court’s exercise of discretion to deny cert. in a series of same-sex marriage cases paved the way for the 2015 Obergefell decision. I don’t remember any denunciations of the “shadow docket” in that context.

Vladeck shows his true colors when he concedes midway through the book that scholars’ attention to the “shadow docket” was triggered by “President Trump’s travel ban.” The Court, Vladeck complains, used unsigned orders to prevent the Trump administration from being hamstrung by numerous lower court nationwide injunctions in immigration and other cases. In an editorial entitled “The ‘Shadow Docket’ Diversion,” the Wall Street Journal –no fan of President Trump—pointed out that

The explosion of high-profile nationwide injunctions by lower courts has…forced the Supreme Court’s hand. Such injunctions started to climb in response to President Obama’s “pen and a phone” governance in his second term, and accelerated as liberal district judges blocked President Trump’s policies.

Justice Kavanaugh has complained about his dissenting colleagues’ “catchy but worn-out rhetoric about the ‘shadow docket.’” Justice Alito correctly pointed out in a speech that the pejorative term “has been used to portray the Court as having been captured by a dangerous cabal that resorts to sneaky and improper methods to get its way.” As the Righteous Brothers’ classic song goes, liberal Court watchers have “lost that lovin’ feelin’” and are now criticizing the “little things”—formerly overlooked– such as unsigned orders. The overheated rhetoric about the “shadow docket” is nothing but sour grapes over the fact that liberal hegemony on the Court is “gone, gone, gone.”