Winning the War

Defeating the Axis Powers during WWII took tremendous resolve, effort, and resources.

This essay first appeared in the Maryville Daily Times, on August 7, 2023 (here).

In last month’s column, I talked about the contribution of Oak Ridge to the Manhattan Project’s development of the atomic bomb, which ended WWII in September 1945. But in order to end the war, the U.S. first had to win the war. Hitler was vanquished in May 1945 (celebrated as VE Day), but the road to victory against the Axis powers (Germany, Italy, and Japan) came at a steep cost: over 400,000 American casualties and incalculable sacrifice (economic and otherwise) by U.S. citizens. Tennessee, including the extensive manufacturing operations once based in Alcoa, played a significant role in the war effort.

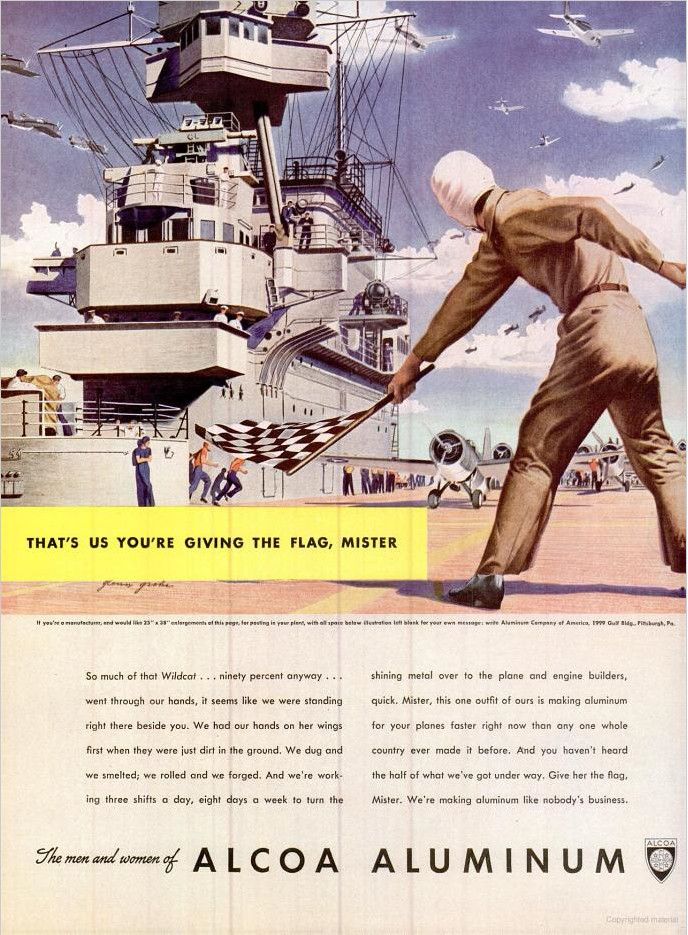

When the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, America was at peace. President Roosevelt understood that the entire nation must devote itself to the war effort in order to defeat the Axis powers’ goal of worldwide conquest. We urgently needed weapons—tanks, ships, airplanes, bombs, guns, and other materiel—in vast quantities. Fortunately, America possessed considerable resources and industrial capacity, and quickly mobilized them to supply a nation suddenly at war. The U.S. especially needed hundreds of thousands of airplanes (fighters, bombers, transports), requiring aluminum far in excess of existing production levels.

The city of Alcoa, founded by the namesake aluminum producer in 1919, played a key role. Producing aluminum is very energy-intensive; smelting operations require massive amounts of electricity. ALCOA, at the time the nation’s dominant aluminum producer, chose its location in Blount County due to its proximity to hydroelectric power (actual and potential) from the Little Tennessee River. The Cheoah Dam (featured in the 1993 movie The Fugitive) was completed in 1919. The federal government augmented ALCOA’s hydroelectric generating capacity with the TVA’s construction of dams–Cherokee, Douglas, and Fontana—that allowed ALCOA to increase its wartime aluminum production 600% and also powered an enormous A-31 dive bomber factory in Nashville (in addition to servicing Oak Ridge).

During the war, ALCOA’s local workforce grew to 12,000, and the newly-built North Plant, covering 65 acres, was the world’s largest manufacturing plant under a single roof. Aluminum sheet produced in Alcoa was used to build 300,000 airplanes during the war. The Vultee aircraft plant in Nashville, staffed mainly by women (dubbed “Rosie the Riveter”) built thousands of military aircraft. East Tennessee made other contributions to the war effort. As recounted by local authors Dewaine Speaks and Ray Clift in their book East Tennessee in World War II, Rohm and Haas Co. (today part of Dow Chemical Co.) made Plexiglas for airplane canopies at a major facility in Knoxville.

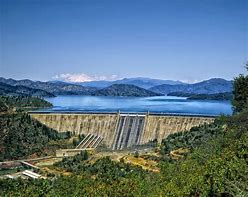

The TVA, in addition to bringing flood control and electrification to East Tennessee, was indispensable to the war effort. Construction of the most impressive dam in the TVA system, Fontana, began in 1941 following TVA’s acquisition of rights to the affected land from ALCOA. The project presented daunting challenges: a remote location, unusual design, and a pressing deadline for completion. At 485 feet tall and 2,365 feet long, the Fontana Dam is an engineering marvel—the biggest dam east of the Mississippi River and the second largest in the U.S.

Construction of the Fontana Dam required 3 million cubic yards of concrete, poured continuously, with staffing 24 hours a day, seven days a week. No holidays. The TVA built a town to house the 6,000 workers and their families. The dam, completed in November 1944, contains three hydroelectric generating units with a net dependable capacity of 304 MW. Between Oak Ridge, ALCOA, and the TVA, the Axis powers never stood a chance.

The Japanese sneak attack on Pearl Harbor was a reckless gamble that, in one fell swoop, American naval power in the Pacific could be obliterated, allowing Japan to consolidate control of Southeast Asia and the Pacific theatre before the U.S. was able to rebuild. It was a calculated sucker punch against a rival Japan realized it could not beat in a fair fight. When the Japanese navy failed to sink the entire U.S. Pacific fleet that fateful Sunday morning—all three of U.S. Navy’s aircraft carriers were unexpectedly away from port, and many other damaged ships were repaired—the architect of the treacherous ambush, Japanese Admiral Yamamoto, knew the gamble was lost. He reportedly recorded in his diary that “I fear all we have done is to awaken a sleeping giant and fill him with a terrible resolve.”

In this, Admiral Yamamoto was exactly correct. President FDR denounced the attack on Pearl Harbor as “a date which will live in infamy.” America entered the war with a fierce determination to win—and did. Our “greatest generation” fought valiantly and heroically. The war effort was successful in large part due to civilian support in places such as East Tennessee, which answered the battle call with extraordinary industrial production that was able to overwhelm the Axis powers. Japan’s unconditional surrender on September 2, 1945, following the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945, would not have happened without the help of many Tennesseans.