Constitutional Conservatives Should Recognize That “Nullification” Is a Chimera, Not a Panacea

Serious problems—and the nation is beset by many–require serious solutions. Conservatives should unite in finding meaningful solutions that will work in the real world. Nullification is not among them.

Sadly, some on the Right continue to embrace the chimera. Here is one example. The Tenth Amendment Center peddles the nullification nonsense (here). I debated the author of S.B. 2775, Jeff Cobble, at an event hosted by the Tennessee Alliance (here).

I. Introduction

The republic today faces dire challenges: enormous federal budget deficits that fuel inflation, unprecedented amounts of national debt, an out-of-control federal bureaucracy (a/k/a the administrative state), an activist federal judiciary, millions of unvetted illegal aliens streaming across our open borders (thanks to the inexcusable dereliction of the Biden administration), the corruption of our legal system (state and federal), and the ascendency of a radical woke agenda in many of our institutions–the universities, K-12 education, the legacy media, Hollywood, Big Tech, and even some mainline churches.

Many Americans—and especially conservatives—are understandably alarmed by the rapidity with which these developments have progressed, and the existential threat they pose to the survival of our great country.

I certainly recognize the dangers posed by the federal Leviathan, and for that reason have been a conservative activist for decades—in a variety of ways: writing, litigating, Republican Party activity (as a donor, volunteer, officer, and candidate), civic engagement, social media, involvement in organizations such as the Federalist Society, etc. I have been called many things, but no one has ever accused me of being a RINO or a squish. Now, however, sensible opposition to the untested and unworkable doctrine of “nullification” is being branded as “RINO.” This is misguided and unjustified. Silly, even.

By way of background, in recent years some conservatives have been advocating “nullification” as a mechanism for states to take back their sovereignty from perceived federal usurpation. The New American magazine and the Tenth Amendment Center have been particularly outspoken in this regard. I have serious qualms about the nullification movement (from the standpoint of efficacy), and a few years ago was prompted to write an article for Law & Liberty entitled “Is Nullification an Option?” My conclusion, as a lawyer and a constitutional conservative, was a qualified “no,” depending on the meaning of nullification, which is used to describe several different things: protest, non-cooperation, or defiance. (The first two are permissible, but largely ineffective; the last is unconstitutional, and futile.)

My interest in the topic stopped there, until recently, when legislators in Tennessee re-introduced a bill (S.B. 2775/H.B. 2795) drafted by Greeneville attorney Jeff Cobble that became the subject of a March 6, 2024 opinion by our excellent Tennessee Attorney General Jonathan Skrmetti (Opinion No. 24-005). General Skrmetti’s opinion concluded that the proposed nullification bill was unconstitutional—a conclusion I shared. General Skrmetti’s opinion ignited the unwarranted ire of some nullification supporters. For that reason, I feel compelled to elaborate on my opposition to nullification. Here it is.

I must preface my comments with a reminder that I share the valid concerns of nullification supporters regarding the degree of federal overreach and the threat that represents to our liberties. Also, to reiterate, different types of actions, all loosely labeled “nullification,” present different issues regarding the legal viability of the purported nullification, as I shall explain. As a retired lawyer who practiced law for 30 years, I look at nullification purely as a legal matter, not as an exercise in theory, political philosophy, theology, [1] mythology, or—dare I say–wishful thinking. [2] Any proposed “solution” to our problems must be legally tenable and not merely aspirational. It has taken many decades for us to get into our current predicament, and extricating ourselves will require sustained hard work and patience. The allure of unrealistic “magical” solutions is a distraction from the difficult task ahead.

States are certainly free to challenge objectionable federal laws and federal policies in court, as Texas is doing with regard to President Biden’s failure to secure the border, and as Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis is vowing to do regarding the Biden administration’s radical Title IX regulations. This is not “nullification,” but merely an example of the interplay between state and federal government under our constitutional system. “Nullification” connotes something else entirely—the presumed right of a state to simply disregard (or even override) federal law (and the decisions of federal courts, including the U.S. Supreme Court) if the state believes that the law or decision is contrary to the Constitution. Article III of the Constitution (which created the judicial branch), the concept of judicial review (recognized by the Supreme Court in the 1803 decision Marbury v. Madison), and the Supremacy Clause of the Constitution (Art. VI) [3] make federal law superior to state law, and empower the Supreme Court as the ultimate arbiter of the constitutionality of challenged laws.

To accomplish “nullification” in the sense promoted by its proponents would require a constitutional amendment. Or secession.

II. The Proposed Bill

Senate Bill 2775, introduced by Sen. Janice Bowling, is titled the “Restoring State Sovereignty Through Nullification Act.” The bill was deferred to “Summer Study” this year, after having failed to pass the General Assembly in 2022 and 2023. The companion bill in the House, sponsored by Rep. Bud Hulsey, is H.B. 2795.

The bill contains six pages of “findings” (Section 3) before getting to the substance. The bill purports to authorize all three branches of Tennessee government (the Governor, the General Assembly, and the courts) to review the actions of all three branches of the federal government (including treaties) to determine whether the federal action (“past, present, or future,” without regard to “any perceived statute of limitation”) is authorized by the U.S. Constitution, after considering the text, the original understanding, and “statements of support for natural law and natural rights by the framers and the philosophers admired by the framers.” Section 5(7). Supreme Court precedents (other than “opinions of the first chief justice,” John Jay, who served from 1789 to 1795) are not to be considered, despite hundreds of years of precedent, our system of stare decisis, and the doctrine of judicial review (established in Marbury v. Madison (1803)).

The Governor can issue a nullification by executive order. Section 9(1). The General Assembly can act on a bill of nullification introduced by a member, or upon a petition of nullification submitted by either: (i) any combination of 10 counties and municipalities, or (ii) 2,000 registered voters. In any event, the matter goes directly to the floor of each house (skipping the committee process) where it is debated and presented for a roll call vote under specified time deadlines. If passed, the nullification bill would become effective immediately upon enactment. Tennessee courts can issue a nullification order in “any case of which [they] overwise [have] proper venue and jurisdiction.”

What is the effect of a nullification finding? If a federal action was found to have exceeded constitutional authority (using the criteria outlined in Section 5), it would “not be recognized as valid within the bounds of [Tennessee]”; it would be deemed “ultra vires” and “null and void”; no government employee in the state of Tennessee (whether state, county, or city) could “assist in any attempted enforcement of said federal action”; and no tax monies collected by state or local governments in Tennessee could be “used to assist in any attempted enforcement of said federal action.” Section 8. Federal actions subject to nullification “are declared void and must be resisted,” whatever that means. Section 6.

What federal actions could be nullified? Almost anything. All Supreme Court decisions, going back more than 200 years. All congressional action. All administrative agency decisions and rules. All presidential executive orders. Even federal policies and standards. Section 4(1).

As far as nullification measures are concerned, S.B. 2775 pulls no punches. It is a “no holds barred” template for Tennessee officials to thumb their noses at the federal government. To my knowledge, nothing like it has ever been enacted—let alone enforced—in our nation’s history.

III. The Attorney General’s Opinion

Opinion No. 24-005 addresses Senate Bill 1092 from the 113th General Assembly, 1st Session, the text of which is identical to S.B. 2775. The opinion was requested by Sen. Richard Briggs, Chairman of the State and Local Government Committee.

In summary, the opinion states:

Senate Bill 1092 is constitutionally infirm. The separation-of-powers doctrine set forth in article II, sections 1 and 2 of the Tennessee Constitution prevents the General Assembly and the governor from nullifying “unconstitutional federal action.” And the Supremacy Clause of the United States Constitution prohibits state legislation aimed at increasing the limited authority of state courts to nullify unconstitutional federal action.

In contrast to the 12-page S.B. 2775, the opinion runs four single-spaced pages. It does not address every aspect of S.B. 2775, but rests on two fundamental defects: (1) by granting nullification authority to the Governor and General Assembly, thereby allowing them to decide that federal action violates the U.S. Constitution, the bill violates the Tennessee Constitution, which limits that function to the judicial branch; and (2) by authorizing state courts to disregard federal laws (whether in the form of executive orders, laws, agency decisions and rules, or judicial decisions) the bill violates the Supremacy Clause of the U.S. Constitution (Art. VI, clause 2), which states that the Constitution and laws of the U.S. “shall be the supreme Law of the Land; and the Judges in every State shall be bound thereby, any Thing in the Constitution or Laws of any State to the Contrary notwithstanding.” (Emphasis added.)

General Skrmetti’s opinion cites numerous authorities in support of his conclusions, including the landmark decision in Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1 (1958). Interestingly, Skrmetti also cited a proclamation by the first Tennessean to serve as President of the United States, Andrew Jackson. Old Hickory had this to say is response to South Carolina’s purported nullification of a federal tariff:

Andrew Jackson, Proclamation No. 26, Respecting the Nullifying Laws of South Carolina (Dec. 10, 1832), reprinted in 11 Stat. 773 (1859) (“[T]he power to annul a law of the United States, assumed by one State, [is] incompatible with the existence of the Union, contradicted expressly by the letter of the Constitution, unauthorized by its spirit, inconsistent with every principle on which it was founded, and destructive of the great object for which it was formed.”). [4]

IV. The Doctrine of Nullification

Proponents of nullification place great emphasis on the 10th Amendment (which merely states that authority not ceded to the federal government in the Constitution is retained by the states), ignore numerous controlling Supreme Court precedents with which they disagree, and selectively rely on fragments of American history (and quotes from various figures in the founding era) to justify the notion that states can choose to ignore the provisions of federal law by deeming them to be extra-constitutional. (Ironically, the “findings” in the proposed bill—similar to recitals in a contract—cite and quote various Supreme Court decisions, including one they claim is illegitimate, Marbury v. Madison.) This may have been a plausible argument under the dysfunctional (and long-defunct) Articles of Confederation, which was superseded by the Constitution drafted in Philadelphia in 1787, but nullification has never been successfully asserted since the Constitution was ratified in 1789.

The near-total autonomy of the states under the Articles of Confederation almost doomed the American experiment. Fighting the Revolutionary War was hampered by lack of adequate funding and centralized decision-making. The Founding Fathers realized that a stronger national government was required, which was the impetus for the Constitution. In order to form a durable union, the states had to surrender some of their sovereignty. That was the compromise reached in Philadelphia in the summer of 1787.

The Constitution, as adopted, is not a Holy Writ. It was not delivered from God like the Ten Commandments. It was negotiated by committee and reflects many compromises due to there being many different points of view. James Madison, credited as the “Father of the Constitution,” was mainly the chief note-taker—the scribe. His original proposal for the Constitution (called the Virginia Plan), which called for representation in the Senate based on each state’s population and the election of the President by Congress, was rejected. The original intent of the Constitution is not determined by consulting the views of any single founder; there were many. Over 1600 delegates were involved in ratifying the Constitution.

The Constitution does not authorize nullification; the Supremacy Clause states the opposite.

Nullification was not even mentioned at the Constitutional Convention in 1787.

The nullification doctrine is plainly unconstitutional and, if followed, would quickly be struck down by a federal court.

The Supreme Court has expressly and repeatedly rejected the doctrine of nullification. U.S. v. Peters (1809); Worcester v. Georgia (1832); Ableman v. Booth (1859); Cooper v. Aaron (1958).

Nullification is no more viable a “solution” than secession, and we know how that turned out.

Proponents of nullification invariably cite the same “evidence” in support of their position. Let us consider the extended history of this misguided theory. [5]

- Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions

In the fractious early days of the republic, the Federalist Party held the White House (President John Adams) and controlled Congress. Motivated by conflicts with France that might lead to war (and which some historians refer to as a “quasi-war”), the Federalists passed the draconian Alien and Sedition Acts of 1798 to suppress political dissent. The Acts (and in particular the Sedition Act) were very unpopular, especially in the opposition party led by Thomas Jefferson, the Republicans. The Supreme Court had not yet established the doctrine of judicial review, pursuant to which laws can be challenged on appeal on the ground they violate the Constitution. This did not happen until 1803 in Marbury v. Madison. The federal judiciary was in an embryonic stage. Accordingly, two prominent Republicans, Jefferson and James Madison, ghost-wrote vehement protests of the Alien and Sedition Acts, contending that the laws were unconstitutional. In 1798, these protests were adopted by the legislatures of Kentucky and Virginia, respectively.

Scholars speculate that the true motivation for these resolutions was political—to foment opposition to the Federalists and their policies. [6] The resolutions were largely ineffective. No other states passed similar resolutions, many rejected them, and several even “wrote resolutions opposing the right of states to declare federal statutes null and void.” [7] The Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions had no legal effect whatsoever. Eventually, the unpopularity (and partisan abuses) of the Alien and Sedition Acts led the Federalists to lose power. Jefferson was elected President in 1800, and Congress allowed the unpopular law to expire. Those convicted of sedition under the Act were pardoned.

In the Virginia Resolution, Madison did not claim that states could unilaterally strike down federal laws. It was simply the expression of protest by the Virginia legislature. Madison used the term “interposition” rather than “nullification.” In response to the counter-resolutions of other states opposing the doctrine of nullification, in the 1800 Report of Virginia House of Delegates, Madison made it clear later that he did not believe the states had the unilateral authority to invalidate federal laws because of their purported unconstitutionality. The 1800 Report recognized that deciding the constitutionality of federal laws is the exclusive province of the federal judiciary, while clarifying that the Virginia Resolution was merely an “expression of opinion” designed to spur debate.

Later, in the wake of the Nullification Crisis (discussed below), Madison made his views unequivocally clear in 1834:

But it follows from no view of the subject, that a nullification of a law of the United States can, as is now contended, belong rightfully to a single State, as one of the parties to the Constitution; the State not ceasing to avow its adherence to the Constitution. A plainer contradiction in terms, or a more fatal inlet of anarchy cannot be imagined. (Emphasis added.)

These views are consistent with an 1830 letter that Madison wrote to Edward Everett, contained in the National Archives. Jefferson, whose nullification rhetoric was more aggressive than Madison’s—bordering on advocacy of secession–played no role in the drafting of the Constitution, and was not even in the United States when the Constitutional Convention was held in 1787. (Jefferson was abroad, serving as the minister to France.) One of his biographers, Dumas Malone, argued that Jefferson—then Vice President–concealed his authorship of the Kentucky Resolution because he feared it would be considered seditious or even treasonous. [8] Therefore, Jefferson’s anonymously-authored views regarding the Constitution must be assigned little weight.

Nullification proponents risibly claim that the Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions “prove” that the framers supported nullification, but the actual history obviously shows otherwise.

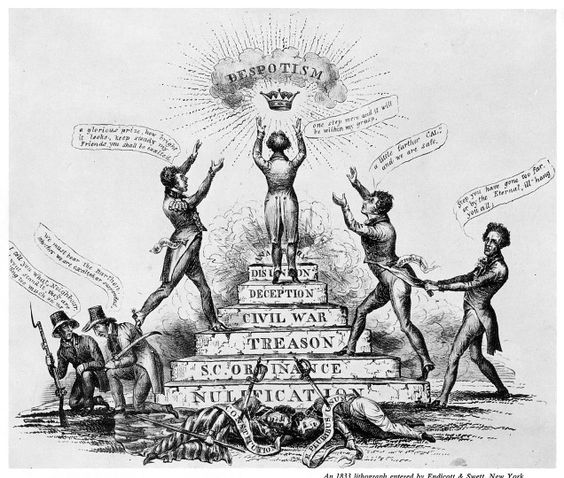

B. Nullification Crisis in 1832-33

The next milestone in the history of nullification occurred in 1832-33. Historians refer to this episode as the Nullification Crisis of 1832-33. Before the authorization of a federal income tax in the 16th Amendment (ratified in 1913), federal revenues were generated mainly by charging tariffs on imported goods. Tariffs were unpopular in the South, which depended on the export of cotton, tobacco and other goods. The imposition of high tariffs to protect northern manufacturers invited retaliation by European nations who purchased southern goods.

John C. Calhoun, from South Carolina, objected to the Tariff of 1828 and asserted that each state has the right to “veto” federal laws if the state believes it encroaches on its rights. (Famed 19th century lawyer and statesman Daniel Webster, disagreed.) In 1832, South Carolina undertook to nullify the tariff and prohibit its enforcement within the state.

President Andrew Jackson denied that South Carolina had the power to nullify federal statutes and threatened to use federal troops to put down any attempt to interfere with the tariff as an act of rebellion—treason, he called it. To Jackson, nullification was tantamount to secession, a result Jackson would not countenance. In President’s words:

I consider, then, the power to annul a law of the United States, assumed by one State, incompatible with the existence of the Union, contradicted expressly by the letter of the Constitution, unauthorized by its spirit, inconsistent with every principle on which It was founded, and destructive of the great object for which it was formed.

South Carolina backed down, and a compromise was reached on the tariff. Constitutional scholar John Eastman points out that

Although a compromise tariff bill ended that particular nullification crisis, Calhoun’s argument metastasized into full-blown secession by South Carolina and her sister states of the confederacy in 1861, drawing the nation into what remains the bloodiest war of her history, interring on the battlefields of Vicksburg, Antietam, and Gettysburg the specious doctrine that the Supreme Court itself had already rejected as incompatible with the Constitution’s Supremacy Clause. (Emphasis added.)

South Carolina was, it should be recalled, the first state to secede from the Union, on December 20, 1860.

C. Slavery and the Fugitive Slave Act

Prior to the Civil War, and enactment of the 13th Amendment, the institution of slavery led to many legal conflicts, especially when non-slave states attempted to interfere with the enforcement of the federal Fugitive Slave Acts of 1793 and 1850. In Prigg v. Pennsylvania (1842), the Supreme Court rejected Pennsylvania’s attempt to nullify the Fugitive Slave Act of 1793. In Ableman v. Booth (1859), the Supreme Court rejected Wisconsin’s attempt to nullify the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 and to prevent the federal courts from reviewing state court decisions or enforcing federal law.

Because the “natural law” argument for nullification is similar to the one asserted in support of secession, the defeat of the Confederacy in the Civil War was thought to resolve the question once and for all. As it turns out, nullification was to resurface for an unsuccessful encore in the 20th century, discussed next.

D. Desegregation

The most recent—and most emphatic—rejection of the nullification doctrine came as a result of intense southern opposition to the Supreme Court’s desegregation decision in Brown v. Board of Education (1954). Brown was a very controversial decision in its day, eliciting more criticism than any other Supreme Court decision of the 20th century. In 1956, 19 U.S. Senators and 82 Representatives from southern states (including some from Tennessee) issued a document entitled Declaration of Constitutional Principles, typically referred to as the “Southern Manifesto,” which condemned Brown as a “clear abuse of judicial power.” Many southern states were engaged in “massive resistance” to the judicial order to de-segregate schools and other public institutions.

In 1957, public opposition to court orders requiring the integration of Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas, emboldened by the resistance of Arkansas Governor Orval Faubus, led to mobs seeking to prevent the enrollment of black students at the previously all-white school. Faubus even deployed the Arkansas National Guard to prevent enforcement of the federal court order. In response, President Eisenhower invoked the Insurrection Act of 1807 to enable troops to perform domestic law enforcement, and ordered federal troops (the 101st Airborne Division of the United States Army) to Little Rock to ensure that federal court orders were complied with.

Arkansas’s open defiance did not go unnoticed in the Supreme Court. In 1958, the Court issued its decision in Cooper v. Aaron, a lawsuit filed by members of the Little Rock School District trying to avoid compliance with the desegregation order. The Supreme Court’s decision was unanimous, and—without precedent—signed by all nine Justices. The Supreme Court rebuked the recalcitrant officials and proclaimed that its interpretation of the Constitution is final and binding. This is the doctrine of judicial supremacy:

Article VI of the Constitution makes the Constitution the “supreme Law of the Land.” In 1803, Chief Justice Marshall, speaking for a unanimous Court, referring to the Constitution as “the fundamental and paramount law of the nation,” declared in the notable case of Marbury v. Madison, 1 Cranch 137, 5 U. S. 177, that “It is emphatically the province and duty of the judicial department to say what the law is.” This decision declared the basic principle that the federal judiciary is supreme in the exposition of the law of the Constitution, and that principle has ever since been respected by this Court and the Country as a permanent and indispensable feature of our constitutional system. It follows that the interpretation of the Fourteenth Amendment enunciated by this Court in the Brown case is the supreme law of the land, and Art. VI of the Constitution makes it of binding effect on the States “any Thing in the Constitution or Laws of any State to the Contrary notwithstanding.” 358 U.S. at 18.

Nullification didn’t work.

The same scenario was repeated in Mississippi in 1962, when President Kennedy sent federal troops to Oxford, Mississippi to quell a riot and overcome public and political resistance to the integration of the University of Mississippi pursuant to federal court orders. Nullification didn’t work.

The following year, 1963, when Alabama Governor George Wallace stood in the schoolhouse door to prevent black students from enrolling at the University of Alabama, President Kennedy federalized Alabama National Guard troops to force Wallace to halt his blockade and submit to a judge’s order ending segregation at the university. Later in 1963, the process was repeated to ensure compliance with a federal court order to integrate Tuskegee High School in Alabama. Nullification didn’t work.

E. Summary

Nullification proponents often contend that the Supreme Court has overridden or usurped the “true meaning” of the Constitution, rendering the Court’s decisions “null and void.” There are several responses to this charge. Whether one agrees or disagrees with a particular Supreme Court decision, one has to concede that the judicial branch was designed to interpret the law, including resolving conflicts between statutes and the Constitution. That is what courts do. The Marbury v. Madison precedent from 1803 recognized that the Supreme Court has the power of judicial review, consistent with Alexander Hamilton’s Federalist No. 78. The Supremacy Clause states that federal law “shall be the supreme Law of the Land,” and “the Judges in every State shall be bound thereby, any Thing in the Constitution or Laws of any State to the Contrary notwithstanding.” Art. VI.

If the Supreme Court is not the ultimate authority in disputes involving interpreting the Constitution, the national government created by the Framers in Philadelphia in 1787 would be subject to the same flaws that doomed the Articles of Federation: the lack of a meaningful central government. As Justice Joseph Story wrote in 1840, without the judicial power created in Article III, “the laws of the Union would be perpetually in danger of being contravened by the laws of the States. The National Government would be reduced to a servile dependency upon the latter for the due execution of its powers.” [9] Regarding the Supremacy Clause, Story had this to say: Allowing states to second guess the validity of federal laws “would be a solecism, so mischievous, and so indefensible, that the scheme could never be attributed to the framers of the Constitution, without manifestly impeaching their wisdom, as well as their good faith.” [10] Indeed, it would reduce the national government to “an idle mockery.” [11]

Finality in constitutional interpretation is critically important because the generality of key constitutional provisions makes good faith disagreement possible. Many nullification proponents believe that the Court has allowed the federal government to exceed the limited powers enumerated in Art. I, section 8. However, reasonable people can come to different conclusions regarding the meaning of phrases such as “general welfare,” “necessary and proper,” and “regulate commerce.” If the Court has made errors in interpreting the Constitution, those errors began more than 200 years ago. The most momentous decision in this regard is McCullough v. Maryland (1819), which held that Congress has implied powers not expressly enumerated in Art. I, section 8.

While I do not necessarily agree with all the Supreme Court decisions disputed by nullification proponents, one must acknowledge that prior to its ratification the Anti-Federalists warned that the Constitution could—and would—be interpreted in that manner. In any event, the mechanism for correcting an erroneous constitutional interpretation is to amend the Constitution through Art. V, or controlling the political branch through elective politics, not nullification by the states.

The term “nullification” is used to mean several very different things. A state is obviously free to state its disagreement with a federal action, whether the disagreement is based on constitutional grounds, or otherwise. Madison called this “interposition.” Mere disagreement—or even strident protest–accomplishes very little. The term nullification is also used to mean non-cooperation by a state, meaning that state resources will not be used to assist the federal government to enforce an objectionable law. This, too, is permissible, but largely ineffective. The federal government has plenty of resources at its disposal and cannot “commandeer” state personnel to enforce federal law. States can even pass laws that are inconsistent with federal law so long as the subject is not “preempted.” For example, some states have legalized the sale and use of controlled substances banned by federal law. Others have recognized “sanctuaries” for illegal aliens. Because the federal government cannot force the states to enforce federal drug laws or immigration laws, this is permissible. S.B. 2775 goes beyond disagreement and non-cooperation.

And, as noted earlier, states can challenge federal laws and policies in court. Texas and Florida do this routinely. Tennessee Attorney General Jonathan Skrmetti does also.

My objection to nullification is limited to the notion that states can unilaterally declare federal actions unconstitutional and somehow prevent the federal government from enforcing those actions in the state (or authorize state courts to refuse to follow federal law as interpreted by the federal courts). This is outright defiance, in the sense threatened by South Carolina in the Nullification Crisis, or by southern states refusing to comply with Brown. S.B. 2775 authorizes all the foregoing variations of nullification. A more carefully tailored bill might obviate my concerns, but would be a waste of time—a meaningless gesture, in my opinion. Even without S.B. 2775, nothing prevents the state of Tennessee from disagreeing with federal laws, refusing to cooperate, going to court to challenge them, or even enacting parallel measures (such as declaring Tennessee to be a Second Amendment sanctuary). Defiance is not a viable strategy.

Nullification proponents refuse to face the fact that the doctrine of nullification has never worked in America. Not in 1798, not in 1832-33, not in the run-up to the Civil War, and not in opposition to Brown. Nullification is illusory—a chimera. It is a fantasy that ignores 200 years of history, controlling Supreme Court precedents, and the plain meaning of the Supremacy Clause of the U.S. Constitution.

General Skrmetti’s opinion that the nullification bill is unconstitutional was, if anything, gentle and understated. One constitutional scholar has stated that “If you believe in nullification, you don’t believe in the Constitution.” This formulation, while provocative, reflects the consensus of mainstream legal thought, even in conservative circles (e.g., Mark Levin, David Barton, John Eastman, the Heritage Foundation, Cato Institute, Americans for Limited Government, Convention of States, Rob Natelson, Myron Magnet).

Nullification is an untenable theory. As libertarian law professor Randy Barnett has said, “Political activists should not waste their precious energies on sketchy constitutional theories such as the assertion of a state power to nullify unconstitutional laws that, for better or worse, have long been rejected by the Supreme Court–as Wisconsin’s was in Ableman v. Booth–that five justices certainly would not today support, and that rest on dubious claims about original meaning.”

John Eastman is emphatic: “Quite simply, although the states retain a residuum of sovereign power, they did not create the national government and therefore have no authority to nullify its enactments. The first three words of the Constitution are, after all, ‘We the People,’ not ‘We the States.’”

V. What Might Nullification Look Like?

Even if it were practicable (which it is not), nullification is a two-way street. If all of the various branches in each state were free to interpret the Constitution in any manner they wished, we might not like the result.

In a liberal state (or in Tennessee under a Democrat governor), the Supreme Court’s Second Amendment decisions in District of Columbia v. Heller (2008), McDonald v. Chicago (2010), and N.Y. State Rifle & Pistol Ass’n v. Bruen (2022) could be subject to nullification, leading to bans or restrictions on the ownership of firearms and ammunition.

A liberal state (or Democrat governor in Tennessee) could unilaterally nullify Dobbs, reinstate Roe v. Wade, and allow abortion mills to resume operation.

A liberal state (or Democrat governor in Tennessee) could nullify Supreme Court decisions approving the death penalty, and abolish capital punishment.

A liberal state (or Democrat governor in Tennessee) could find a constitutional pretense to declare itself a sanctuary for minors wanting to have sex-change surgery without their parents’ consent.

A liberal state (or Democrat governor in Tennessee) could nullify Supreme Court decisions banning race-based affirmative action, and implement racial preferences in admissions, hiring, contracting, etc.

A liberal state (or Democrat governor in Tennessee) could expand the recognition of same-sex marriage in Obergefell v. Hodges (2015) to require states to allow incest, bestiality, polygamy, and even to abrogate the age of consent for minors.

A liberal state could ignore the Supreme Court’s unanimous decision in Trump v. Anderson and remove President Trump from the ballot pursuant to Section 3 of the 14th Amendment on the bogus grounds that he was engaged in insurrection or rebellion against the United States.

If Brown v. Board of Education was nullified, schools could return to segregation.

If multiple states adopted the nullification doctrine, we could end up with a patchwork quilt in which the federal income tax was enforced in some states but not others, constitutional rights were not uniformly observed, and national standards were replaced with ad hoc local decision-making. Without uniformity of interpretation of the Constitution, chaos would ensue. We would be back to the dysfunctional days of the Articles of Confederation.

“Turning back the clock” to an era pre-dating the New Deal, or the Great Society, or the Warren Court, or even the tenure of Chief Justice John Marshall, would open a Pandora’s Box of unintended consequences.

VI. The Path Forward

This does not mean that conservatives must passively accept the status quo. Patriots do not need the doctrine of nullification to push back against the federal Leviathan. Instead of symbolic resolve in the form of S.B. 2775, our elected officials should demonstrate actual resolve.

Yes, there are bad Supreme Court decisions. Constitutional amendment per Art. V, and appellate litigation are the mechanisms for correcting erroneous interpretations of the Constitution. Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton is an example of a crusading state A.G. He doesn’t need the nullification doctrine to empower him.

If you want to use nullification by the states as a check on federal power, support a constitutional amendment to make it the law of the land. [12]

Elect constitutional conservatives to local, state, and national office. Support conservative candidates with your time and treasure.

Pass state laws challenging federal policies (such as the obligation to educate illegal alien children, or to accept asylum seekers and/or refugees), and litigate against the federal government to defend those laws.

Recognize the importance of maintaining Republican control of the White House and Senate, and make the appointment of sound constitutional originalists to the federal bench a top priority.

Use state government as a bully pulpit to educate citizens about the cost, burden, and error of federal policies.

Reject federal funds that compel states to comply with policies antithetical to the state’s values. The Department of Education doles out money with unacceptable strings attached.

Encourage the Tennessee Attorney General to challenge executive orders, federal mandates, and overreaching laws in federal court.

Assert Tennessee’s plenary power to govern itself: Combat illegal immigration by requiring Tennessee employers to screen employees using E-Verify; don’t grant occupational and professional licenses to illegal aliens; cut off welfare and other state-funded benefits to illegal aliens; enhance sentences for crimes committed by illegal aliens.

When a federal policy presents an existential threat to the state, such as President Biden’s reckless open border policy threatened Texas, fight back by passing laws and suing the federal government. Texas is fighting to preserve its sovereignty without having a nullification statute.

Stop the indoctrination of Tennessee schoolchildren and college students with curricula promoting aberrant lifestyles (LGBTQ), divisive identity politics (DEI), and socialism (social justice). The University of Tennessee should be a conservative flagship in the Volunteer State. Civics and American history should be required subjects in Tennessee high schools.

Stop doling out corporate welfare to woke companies in the name of “economic development.” Tennessee has plenty of natural incentives for businesses (land, water, electrical power, right-to-work) without bribing them to move here.

Tennessee conservatives should devote the effort and energy being wasted on futile nullification bills on fixing the structure of the Republican Party in Tennessee: close the primaries, get rid of restrictive definitions of “bona fide” status; encourage the Tennessee Republican Party to embrace grassroots activism (by, among other things, conducting biennial reorganization meetings using mass conventions), similar to other red states such as Texas and Florida.

Patriots wishing to make a difference should run for a seat on the Tennessee Republican Party’s State Executive Committee, form a majority, and elect a genuine conservative as Chairman. Tennessee could have the most robust (and most conservative) Republican Party in the country.

There are plenty of things Tennessee conservatives can do without the quixotic and chimerical nullification doctrine.

Just do it.

As Benjamin Franklin said following the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia, the Founding Fathers created a republic, if we can keep it. Nullification is secession-lite. Constitutional conservatives should not be embracing such reckless rhetoric.

Finally, Attorney General Skrmetti is on our side. Tennessee conservatives must work with—and support—state officials who are on the same team. Knee-jerk opposition to everything “the leadership” does in Nashville is not constructive. Embracing fringe positions that have no realistic hope of passage (or achieving real-world results) simply marginalizes the conservative movement. We can do better.

Footnotes

- Some nullification proponents treat the words of the Constitution (or the Federalist Papers) as Scripture, quote various framers as if they were Apostles, and regard the federal courts as Pharisees. To them, divining the “true meaning” of the Constitution is like religious rapture. Some advocates admit that their calling is a form of “ministry.” In contrast, I approach constitutional interpretation the same as any other legal text. One has to take into account judicial decisions by the nation’s High Court.

- As one commentator observed, “Like a lot of theoretical principles, nullification becomes more popular when it aligns with one’s preferred course of action.”

- Art. VI, clause 2, provides: “This Constitution, and the Laws of the United States which shall be made in Pursuance thereof; and all treaties made, or which shall be made, under the Authority of the United States, shall be the supreme Law of the Land; and the Judges in every State shall be bound thereby, any Thing in the Constitution or Laws of any State to the Contrary notwithstanding.” (Emphasis added.)

- Ironically, given President Jackson’s forceful disagreement with nullification, S.B. 2775 cites and quotes Jackson in its “findings,” in support of nullification.

- In the interest of brevity, this overview will not attempt to discuss every instance in which nullification was asserted, and rejected, including 19th century disputes involving treaties, Ohio’s attempt to tax the Bank of the United States (voided in Osborn v. Bank of the United States [1824]), and Georgia’s assertion of control over Cherokee land.

- See Charles Slack, Liberty’s First Crisis (2015).

- Lauren Moxley Beatty, “The Resurrection of State Nullification—and the Degradation of Constitutional Rights: SB8 and the Blueprint for State Copycat Laws,” 111 Georgetown Law Journal 18, 24 (2022).

- Dumas Malone, Jefferson and the Ordeal of Liberty (1962) (Volume 3 of Jefferson and His Time). Another scholar states that “Though [Jefferson] would not acknowledge authorship until decades later, putting pen to paper in such a way represented a real risk, especially by Jefferson’s careful, cautious standards. Should he be discovered as the author, essentially suggesting that states could repudiate federal law, he might be opening himself to charges of sedition.” Slack, supra note 6, at 164.

- Joseph Story, A Familiar Exposition of the Constitution of the United States 226 (Regnery ed. 1986).

- Id. at 302.

- Id.

- William J. Watkins proposes such an amendment in his 2004 book, Reclaiming the American Revolution: The Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions and Their Legacy.