Fear and Loathing in the Lone Star State

A respected writer sullies his legacy with a tendentious partisan screed

This essay originally appeared in Law & Liberty on April 22, 2019 (here). Thanks to Real Clear Policy and Real Clear Books for the links!

When asked by Law & Liberty if I would be interested in reviewing Lawrence Wright’s new book, God Save Texas, I had mixed feelings. I greatly enjoyed two of Wright’s previous books, The Looming Tower (2006) and Going Clear (2013), both deeply-researched and impressively-reported works of nonfiction. Wright’s journalism also inspired the acclaimed documentary Three Identical Strangers (2018), which fascinated me. Wright is a Pulitzer Prize-winning author and longtime staff writer for The New Yorker, who happens to live in Austin, Texas (as I do), the state capital and the home of the flagship campus of the University of Texas. Wright is unquestionably a talented writer knowledgeable about his (and my) adopted state.

At the same time, I was aware that Wright is a liberal Democrat deeply disenchanted with the state’s political orientation in recent decades. Wright’s latest book, subtitled A Journey into the Soul of the Lone Star State, consists of an extended (and self-referential) meditation on the history, culture, and politics of Texas. (It is also a literary memoir of sorts, as well as a recycling—somewhat disjointedly and repetitively–of some past Texas-themed articles.) I have grown familiar with the smug contempt with which many Austin progressives regard the state’s conservative elected officials (and, by implication, the “unenlightened” provincial voters who support them).

The scorn is reciprocated; former Texas Gov. Rick Perry used to describe Austin as “a blueberry floating in a bowl of tomato soup,” and conservatives in Texas often deride the state capital as “The People’s Republic of Austin.” Texas Monthly, the Austin-based, left-leaning magazine where Wright used to work, has adopted a tone of snide condescension toward ordinary Texans—the unwashed masses, or “deplorables”–as its official editorial position. Of course, many liberals in Texas reside outside of Austin as well, but dating back to the early 1960s—Billy Lee Brammer’s roman a clef of political intrigue, The Gay Place, was published in 1961—Austin has served as the intellectual nucleus for the state’s progressives. Austin has long aspired to be the Berkeley of Texas. As Wright himself concedes, Austin “sees itself as standing apart from the vulgar political culture of the rest of Texas, like Rome surrounded by the Goths.”

My instinct, therefore, was that Wright’s latest book would be marred by this one-sided—and narrowly-parochial–ideological perspective. My trepidation was reinforced by Kevin Williamson’s brutal review of God Save Texas in the Claremont Review of Books, entitled “Austin City Limits.” (Williamson is a native of the Texas Panhandle and a UT alumnus.) Well, it turns out that my instincts were correct. God Save Texas, although undeniably well-written, is full of sanctimonious disdain for the Lone Star State, save music, food, bike riding, wildflowers, bird-watching, Big Bend national park, and Austin itself. Wright acknowledges early on that he “could [not] have lasted in Texas if it were the same place [he] grew up in,” and has considered leaving since re-settling here in 1980, as if the state should be grateful that he deigned to stay. But the changes are not all good, either.

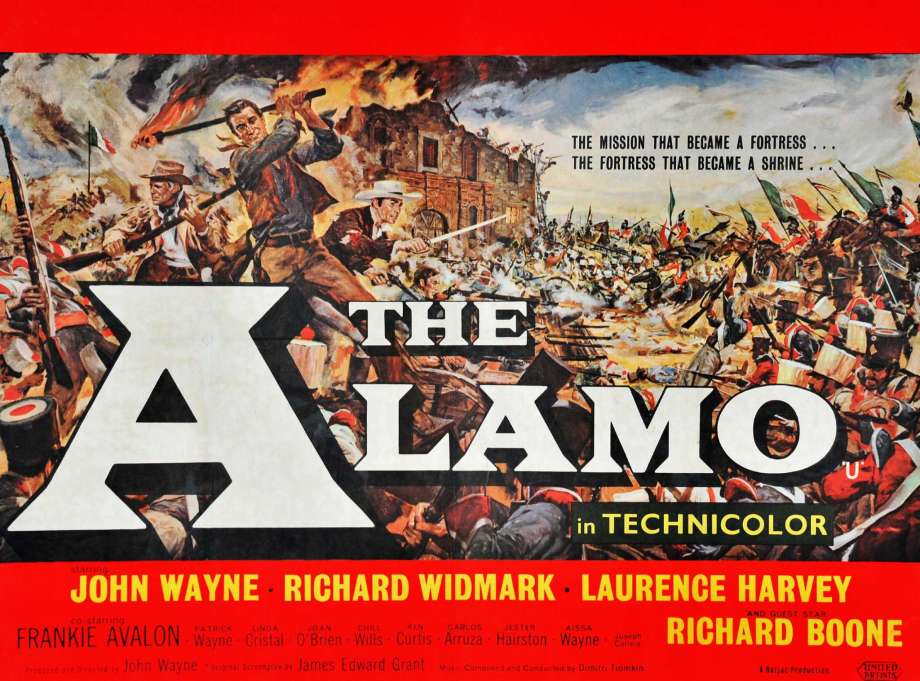

Wright bemoans “ugly” suburban sprawl, endless “cruddy” strip malls, and truck stops (especially the Buc-ee’s chain), as though these things are unique to Texas, and maintains a book-length sneer at the Lone Star State: “Texas has nurtured an immature political culture that has done terrible damage to the state and to the nation”; the 1960 movie The Alamo, starring John Wayne, was “our creation myth”; the Texas Revolution, which led to independence from Mexico in 1836, was marred by the “original sin” of slavery; fracking, which has made the U.S. the world’s leading oil producer, is a “dark bounty”; the state legislature “is slavishly devoted to the oil-and-gas industry”; the state’s boom-and-bust economy is “a civilization built on greed and impermanence”; and the legacy of the Confederacy is “shameful.” Austin liberals forever pine after one-term Governor Ann Richards and the spiteful partisan “humorist” Molly Ivins (both departed); Wright predictably follows suit.

The trite, mean-spirited clichés continue: Wright presumes that racism accounts for the differing fortunes of major league pitchers Nolan Ryan and J.R. Richard, briefly teammates on the Houston Astros; the state’s political leadership “is far more right wing than the general population”; opposition to the climate change agenda is due to “abject submission to the oil and gas industry”; rugged individualism is a “myth”; Wright compares Texas’s lieutenant governor, Dan Patrick, whom he openly loathes, to Infowars conspiracy maven Alex Jones, and claims, on purely partisan grounds, that “the Texas Patrick seeks to create is one of exclusion”; “the NRA has permanently changed America”; and Wright falsely maintains that Dallas at the time of JFK’s assassination in 1963 was a city “where there were scarcely any Democrats,” even though the mayor at the time was a Democrat (as were virtually all elected officials in Texas, including the then-governor, John Connally).

Wright continues in this partisan vein, mocking Republican elected officials while blowing kisses to his liberal heroes (nearly all Democratic pols qualify as such). Conservatives are referred to as “ultraconservative” or “right-wing.” Voter ID laws, pro-life legislation, and opposition to same-sex marriage and illegal immigration “fortify the political strength of white evangelicals who feel threatened by rising minorities and changing social mores.” Conservative policies are described as “heartless,” “callous,” and “stiff-necked political philosophy.” Wright compares opponents of sanctuary cities to “a mob of flesh-eating zombies.” The election of Donald Trump “unleashed prejudices.” Declining state funding for public schools may be due to “racism,” he speculates.

In contrast, throughout the book Wright treats liberal subjects with kid gloves: a leftist law professor is described as “erudite”; the vulgar LBJ was “the most progressive president since Franklin Roosevelt”; a failed gubernatorial candidate, Wendy Davis, was “a glamorous blonde”; and Wright adoringly recalls Richards, the last Democrat to serve as governor of Texas (whom George W. Bush defeated in 1994) as “the most memorable” governor in his lifetime, who was “incredibly vivid,” with a “blinding pompadour,” a “switchblade sense of humor,” “a wonderful smile,” “icy blue eyes,” and “the most amazing drawl.” Wright smears Republican officials who were charged or convicted of crimes even when they were ultimately vindicated as the victims of partisan, baseless prosecutions, and then mocks them for appearing on Dancing with the Stars. Wright unfairly demeans Gov. Greg Abbott, a high school track star who was grievously injured—and paralyzed–by a falling tree after he graduated from law school, suggesting that it was hypocritical for Abbott to recover damages from the property owner and, years later, to support civil justice reform.

Wright reserves his most caustic vitriol, however, for Lt. Gov. Patrick’s advocacy of a bill that would have restricted access to government-operated bathrooms, locker rooms, and shower facilities to those of the designated biological sex, in order to protect the privacy and security of their users (including public school students). The bill, S.B. 6, “embodied the meanness and intolerance that people tend to associate with Texas.”

The only Republican politician Wright depicts in a flattering light is former House Speaker Joe Straus, a political moderate who rose to power with the support of Democratic House members and thereafter used his leadership role consistently to foil conservative policy initiatives. Several chapters read like a self-serving Straus press release, evening the score with his conservative nemeses.

Wright, who speaks fondly of California, laments that “as a Texan I sometimes bridle at the elite disdain and raw contempt that Californians express toward my state,” but this rings hollow, or at least lacks self-awareness. God Save Texas reeks of “elite disdain” and “raw contempt.” Wright could be describing his own ambivalent sentiments toward the Lone Star State, which he calls a “gringo colossus.” For reasons that seem inexplicable, Wright looks forward to being buried in the Texas state cemetery in Austin, alongside many notable Texans he reviles, as well as 2,000 Confederate soldiers. “Nothing says commitment like a burial plot,” he quips. His initial application to be interred in the state cemetery was rejected by then-Gov. Rick Perry; Wright had to re-apply.

The book ends with an encomium to the Texas Tribune, a progressive political advocacy platform that masquerades as a news organization: “no other state needs it more,” he remarks, never missing a beat. Wright, alas, is still “that pitiable figure” he says he used to be—“a self-hating Texan.” Wright recalls that one of his editors at The New Yorker asked him to “explain Texas,” because he couldn’t understand why Wright lived there. Wright claims that he wrote God Save Texas to answer that question. As a friendly reviewer in Texas Monthly noted, Wright’s book reads like diary entries from “inside a troubled marriage,” leading “a reasonable person to wonder just why it is that Wright has stayed wedded to Texas all these years.” Readers will scratch their heads in puzzlement, as I did. By trash-talking his home state, Wright only diminishes himself.