The Perilously Impermanent Past

Roy Rogers is not the only American icon facing the end of the trail in the 21st century. In order to achieve primacy, the leftist mythology requires that the pantheon of American heroes be dethroned.

This essay originally appeared in Law & Liberty on February 18, 2021 (here). Thanks to Power Line, Instapundit (here), Tennessee Conservative News (here), and Real Clear Policy!

Change, while inevitable and sometimes necessary, can be disconcerting if it is too rapid, far-reaching–or misguided. Attitudes and beliefs are obviously not frozen in time. As our culture evolves, prevailing conventions are subject to revision, and in some cases become superseded or even obsolete. This is not necessarily bad—or good—but can provoke reflection on the impermanence of the past. Mere nostalgia—sentimentalizing the past for its own sake–must be distinguished from legitimate concern about the loss of symbols society once embraced, especially if they represent important bourgeois values that define our national character.

The past, it turns out, holds a precarious grasp on the present and can be quite impermanent—even ephemeral. History, as it was taught and understood in the mid-20th century, is under assault. We forget—or, worse, repudiate–the past at our peril. Our shared history binds us together as a nation, as Abraham Lincoln noted in his First Inaugural Address when he invoked “the mystic chords of memory” in the hope that our common history would “swell the chorus of the Union.”

Ronald Reagan famously said that “Freedom is a fragile thing and it’s never more than one generation away from extinction.” The reason, he explained, is that “we didn’t pass it on to our children in the bloodstream.” Like all other beliefs, if devotion to freedom is not passed on by one generation to the next, it is lost. He made that statement in 1961 when delivering his stump speech as a spokesman for General Electric, and reiterated the point many times as Governor of California and President of the United States. Reagan’s point was broader than the fragility of freedom; the transmission of any idea, including the bourgeois values that undergird western civilization, depends on one generation passing the baton to the next. Increasingly, the generational handoff is aborted, for a variety of reasons—often by design.

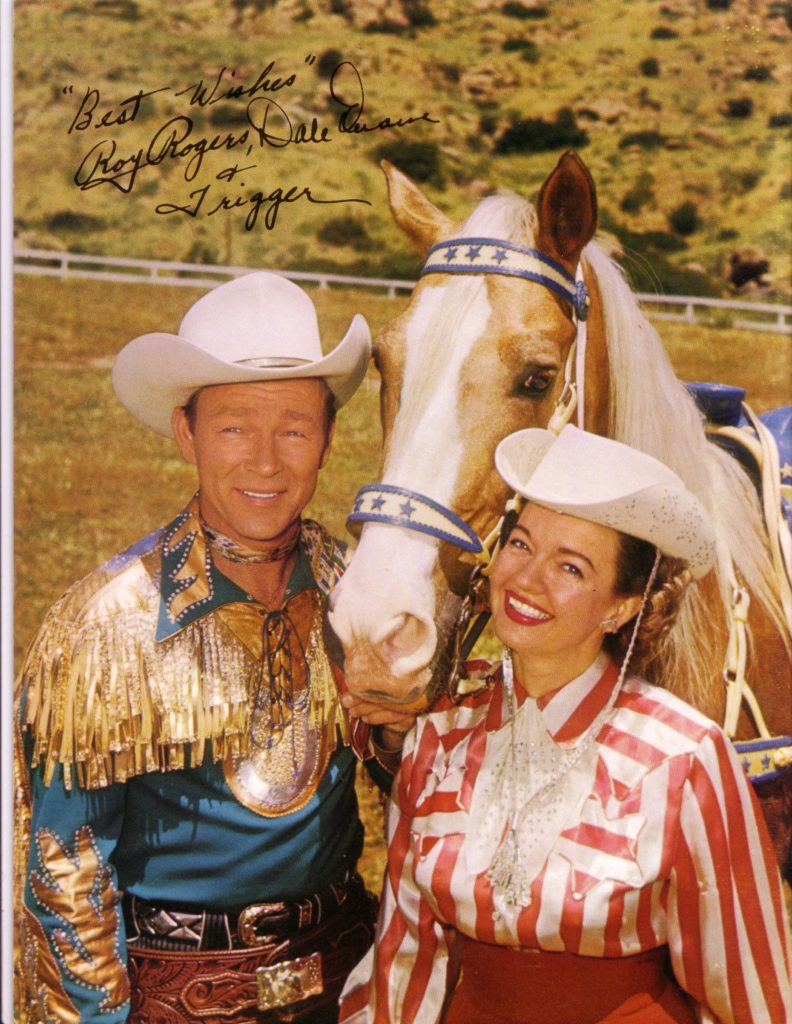

Cultural figures—especially those regarded as heroes–tend to embody the current zeitgeist. Celebrating heroes reinforces shared values and makes a civil society more cohesive. Sometimes a public figure important to one era has no attraction to a later era. Some mid-century icons have retained their appeal–Elvis Presley and James Dean, for example. Others have disappeared down the fickle memory hole. Roy Rogers was extraordinarily popular over the course of his career from the 1930s into the 1960s. A “singing cowboy” who surpassed Gene Autry as a matinee idol, Rogers was a recording star (by himself, with his wife Dale Evans, and with the Sons of the Pioneers), a box office hit who starred in nearly 100 movies, and host of long-running radio and television shows. The Marriott Corporation operated a chain of fast-food restaurants named after him.

In his heyday, Rogers’ image was a marketing sensation—second only to Walt Disney. His obituary in the New York Times reported that “In the late 1940’s and early 50’s, more than 2,000 fan clubs declared their fidelity to the cowboy couple. More than 400 licensed products bore their names and visages, and Mr. Rogers’s picture adorned 2.5 billion boxes of cereal.” I remember going to school as a child with a Roy Rogers lunch box. Rogers died in 1998, followed by Evans in 2001.

Their museum, the Roy Rogers-Dale Evans Museum in Victorville, California, was a popular tourist attraction for more than 35 years, beginning in 1967. It contained a trove of unique memorabilia, including his mounted golden palomino, Trigger; his German Shepherd, Bullet; his Nudie-designed car, adorned with silver dollars, chrome-plated pistols, horse shoes, and the like; and his trusty Jeep, Nelly Belle. I visited it once and was enchanted. Alas, no one under the age of 40 remembers Roy Rogers, or cares. His son, Dusty, moved the museum from California to Branson, Missouri in 2003 due to declining attendance. Moving did not improve the situation. The museum failed altogether in 2019 and the contents were auctioned off last year. A California newspaper mournfully lamented the demise with a story entitled “End of the trail for Roy Rogers Museum.”

Just because something or someone was once popular doesn’t connote lasting cultural significance. Mr. Ed and Sing Along with Mitch are examples of Sixties-era kitsch that have gone the way of turquoise-colored décor and avocado green appliances. Naysayers can likewise dismiss the fall into obscurity of the King of the Cowboys as just deserts for a corny pop culture relic of the Fifties, but Roy Rogers was more than that. He has three stars on the Hollywood Walk of Fame (for movies, radio, and television) and is the only person to be elected to the Country Music Hall of Fame twice. According to the New York Times, at the peak of his popularity during the 1950s, “A survey conducted by Life magazine among children found that when they were asked whom they most wanted to emulate, Mr. Rogers matched Franklin D. Roosevelt and Abraham Lincoln.”

Could it be that Rogers has fallen out of favor because he was the wholesome hero who always wore the white hat? Was his rapid decline in status from beloved icon to forgotten has-been due to his profession of religious faith that enabled him and his wife to stoically overcome personal tragedy? Could it be that Roy Rogers is forgotten because the qualities he embodied are no longer valued in the 21st century? Is the appeal of pop figures such as Miley Cyrus, Ke$ha, Nicki Minaj, or Cardi B to modern audiences due to their vulgarity and nihilism, in contrast to the multi-talented, G-rated Rogers and Evans? Tastes change, of course, but can anyone seriously argue that the song “WAP” is a cultural or aesthetic advance over Evans’ theme “Happy Trails”? This is progress?

John Wayne provides a similar example. Once the quintessential exemplar of western manhood, universally revered as The Duke, Wayne has fallen in popular esteem since his death in 1979. Wayne’s remarkable acting career spanned the silent age of the 1920s to his final film, The Shootist, in 1972. Best known for his role in John Ford classics such as Stagecoach (1939), The Quiet Man (1952), The Searchers (1965), and The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962), Wayne appeared in a total of 179 film and television productions. A top box office draw for three decades, he won an Academy Award for Best Actor for his role in True Grit (1969).

Wayne’s outspoken conservative views did not detract from his appeal during his lifetime. He was particularly celebrated in his adopted hometown of Orange County, California, where the airport was named in his honor in 1979. In recent years, his iconic persona has come under attack, based on allegedly racist comments he made in a 1971 Playboy interview. Last year, his alma mater, the University of Southern California, removed an exhibit dedicated to Wayne—surely the most illustrious alumnus of USC in the film world–from its School of Cinematic Arts. Progressive activists are urging that Wayne’s name and likeness (in the form of a nine-foot bronze statue) be removed from the Orange County airport, although to date the Board of Supervisors has resisted the change. Wayne remains in the Left’s crosshairs.

Once idolized as a symbol of patriotism, toughness, and bravery, Wayne is now reviled in his former home state as a misogynist, racist, and homophobe—based on some snippets of a 50-year-old magazine interview. The cancel culture threatens to erase Wayne’s significant cultural legacy, which cynics would argue is precisely the point. Westerns—Wayne’s principal genre—tend to depict a binary world of good (heroes) versus evil (villains). Post-modern nihilism favors ambiguity (indeterminism), if not outright reversal of the roles.

This phenomenon is not limited to blue states such as California. In Texas, a 12-foot bronze statue honoring the Texas Rangers (namesake of the local major league baseball team) was removed from the airport terminal at Love Field in Dallas last year in the wake of the death of George Floyd. The impetus was publication of a revisionist book (Cult of Glory) about the legendary law enforcement unit that depicted the Rangers as violent thugs and agents of oppression. The statue, which had welcomed travelers since it was installed in the early 1960s, was hurriedly removed as a symbol of police brutality.

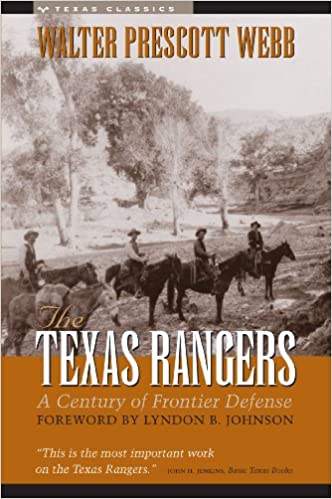

The Texas Rangers, who trace their origins to 1823, have long been regarded as synonymous with taming the Texas frontier. The elite law enforcement agency is honored in The Texas Ranger Hall of Fame and Museum in Waco, a state-designated shrine that has received three million visitors since it opened in 1968. Texas historians have given respectful homage to the Rangers’ colorful record. In 1935, University of Texas history professor Walter Prescott Webb wrote the leading account, The Texas Rangers: A Century of Frontier Defense. The second edition, issued in 1965, included a Foreword by President Lyndon B. Johnson—a noteworthy endorsement. Other esteemed historians have tilled the field. Robert M. Utley, former chief historian of the National Park Service and founding member and former president of the Western History Association, wrote a highly-acclaimed—and balanced–two-volume series published by Oxford University Press: Lone Star Justice (2002) and Lone Star Lawmen (2007).

Most Americans are familiar with the Texas Rangers, as the lawmen who tracked down the notorious outlaws Bonnie and Clyde, in addition to various other marauders, bank robbers, bootleggers, smugglers, cattle rustlers, horse thieves, lynch mobs, armed militias, kidnappers, and serial killers in Texas’s tumultuous and complicated history. Despite this thorough airing of the Texas Rangers’ nearly 200-year record, a single progressive hatchet job in 2020, tendentiously characterizing the Rangers as “very skilled executioners on the behalf of the white power structure,” consigned the venerable law enforcement unit to oblivion. Poof! The statue at Love Field was promptly mothballed. Such is the cancel culture.

An institution even more sacred to Texans than the Rangers is the Alamo in San Antonio, the scene of the 1836 battle in which Santa Anna’s Mexican army slaughtered nearly 200 valiant defenders, led by Lt. Col. William B. Travis and Jim Bowie. The casualties included the famous frontiersman, Davy Crockett. Generations of Texas schoolchildren have memorized Travis’s “Letter to the People of Texas & All Americans in the World,” a futile plea for reinforcements that ended with these stirring words: “I shall never surrender or retreat…. If this call is neglected, I am determined to sustain myself as long as possible & die like a soldier who never forgets what is due to his own honor & that of his country—Victory or Death.” The Travis letter is regarded as the most famous document in Texas history.

Although the unsuccessful defense of the Alamo was a debacle for the Texas rebels, the annihilation of the defenders, followed by Santa Anna’s desecration of their corpses, inspired the rebel army led by General Sam Houston to rout the Mexican forces six weeks later, at the Battle of San Jacinto. This was the decisive conflict in the Texas Revolution, leading to independence for the Republic of Texas. The rallying cry of the outnumbered Texans was “Remember the Alamo!” During the 1936 Texas Centennial celebration, the state of Texas provided $100,000 for a monument at the site of the Alamo, commissioned from sculptor Pompeo Coppini. The Cenotaph, entitled “The Spirit of Sacrifice,” incorporates images of the Alamo garrison leaders and the names of known Alamo defenders who were slain in the battle. The monument was dedicated on November 11, 1940. Texans regard the Alamo as hallowed ground.

So things stood until recently, when Texas Land Commissioner George P. Bush and city leaders in San Antonio decided that the Alamo should be “reimagined,” and the Cenotaph relocated. Imagine “relocating” the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier in Arlington National Cemetery! Many Texans were understandably outraged by the plan. Even though the Alamo is the state’s top tourist attraction, the scene of the 1836 battle—described by some Texans as “our American Thermopylae”—rankles some elected officials in predominantly Hispanic San Antonio. District 1 Councilman Roberto Trevino, an advocate of the “reimagining,” objected to the traditional Alamo narrative, “a story that makes the Mexican a villain.” The “solution” was to recast the Alamo as a multicultural site with “multiple layers of more than 300 years of history.” The goal was to make the Alamo more “inclusive” by focusing on “telling the complete story,” not just the 1836 battle, but also giving “equal billing” to “various epochs,” including the indigenous “Coahuiltecan tribes who lived on the land even before the Spanish established the Mission San Antonio de Valero.”

Alamo defenders, adamant that the shrine to Texas valor needed no “reimagining,” ultimately thwarted Bush’s plans after an extended fight–at least for now. Revisionist historians risibly demonize the Alamo as a “symbol of whiteness” and even “the largest statue to the Confederacy in this country.” The battle is not over.

These examples form a pattern. The past is under attack, and in some cases is disappearing. Our history is being rewritten. The common goal of the 1619 Project, renaming schools and streets, and defacing or removing statues and memorials in the image of imperfect historical figures (a group that to date includes Christopher Columbus, George Washington, Abraham Lincoln, Thomas Jefferson, Francis Scott Key, Ulysses S. Grant, and Junipero Serra) is the erasure of the past, so it can be replaced with the Left’s narrative. Predictably, the progressives’ purge did not stop with cancellation of Robert E. Lee and other Confederate symbols. That was just a warm-up. As Orwell warned, “Who controls the past controls the future.”

Defenders of history should emulate William Travis at the Alamo, and take a stand.