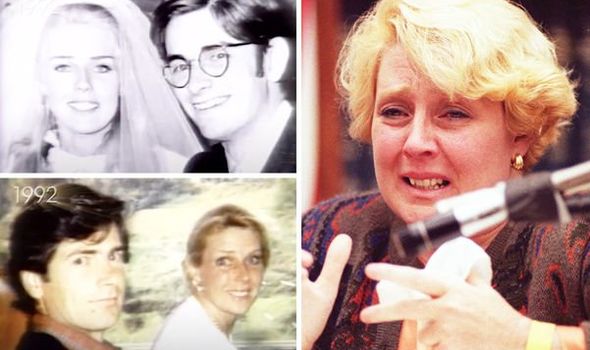

Dirty John 2: The Betty Broderick Story

Season 2 of this true crime series airs the San Diego legal community’s dirty laundry. Betty Broderick was raging against a corrupt ruling class as well as an adulterous, disloyal husband.

I confess that I enjoyed season 1 of Dirty John, the Netflix series based on L.A. Times reporter Christopher Goffard’s reportage of an ill-fated romance turned true-crime thriller based in Orange County, California. Goffard is an excellent journalist, I have long enjoyed the true crime genre (reading about the courtroom exploits of Louis Nizer and F. Lee Bailey in my youth inspired my interest in attending law school), and many of the locations depicted in season 1 were familiar to me because I lived in southern California for over 30 years.

Season 2, released on May 31, is even better. It tells the story of the epically-bitter divorce between prominent San Diego attorney Daniel Broderick and his wife, Betty, who was the mother of his four children. It does not spoil the story to reveal that Betty ultimately shoots to death her ex-husband and his younger—trophy–wife, with whom he had been carrying on an affair prior to the divorce and whom he married shortly after the divorce was final. The story was widely reported at the time, especially in southern California newspapers.

I find the tale fascinating for several reasons. I practiced law in San Diego during the time the events took place. (Dan filed for divorce in 1985 after 16 years of marriage; Betty killed Dan and his new wife, Linda Kolkena in 1989; and the highly-publicized murder trials took place in 1990 and 1991, with the first trial ending in a hung jury.) Prior to the divorce, the Broderick family lived on Coral Reef Avenue in La Jolla, near a house I later owned on Mount Soledad. While I never met Betty or Dan Broderick, the cast of characters and locations in season 2 invoke many fond memories of San Diego in the 1980s and 90s.

Viewers may find certain elements of the story to be far-fetched, such as Betty’s anger and frustration when the local bench seemed to be biased in favor of her husband, a successful medical malpractice plaintiff’s lawyer. Dan was able to get sole custody of the four children (and therefore relief from paying child support), an order permitting him to sell the marital home on Coral Reef (community property) without her consent, and other favorable rulings that Betty was convinced were due to the cozy relationship Dan had with local judges. Betty also had difficulty finding a local lawyer who would represent her in the divorce. Her perception was that the San Diego legal community was a close-knit fraternity that took care of its own.

Based on my knowledge of the San Diego legal community during that period, Betty’s impressions are entirely plausible. In the 1980s, San Diego’s lawyers were an insular group. In contrast to Los Angeles, a dynamic metropolis 120 miles to the north (albeit geographically separated by Camp Pendleton), San Diego was still a sleepy navy town, serviced by a single-runway airport. The city’s law practice was local; branch offices and consolidation of law firms was not yet a thing. As an economic and legal cul-de-sac, San Diego was dominated by an establishment of insiders who aggressively enforced a hierarchy of status and influence. The pecking order was unwritten but well defined. What I am describing is a fiefdom, with an Old Guard running the show.

When he graduated from Harvard Law School, Dan went to work for San Diego’s oldest and largest law firm, Gray, Cary, Ames & Frye (subsequently absorbed via merger by DLA Piper). Gray Cary was the apex law firm in the city’s hidebound legal community. Several Gray Cary partners served (or would serve) on the federal bench—Clifford Wallace, Rudi Brewster, Marilyn Huff, Bill McCurine, and James Stiven—and Gray Cary lawyers tended to dominate the organized bar. Gray Cary represented the largest institutional clients in San Diego. Gray Cary lawyers—and alumni of the prestigious firm—were at the top of the legal food chain. The firm’s preeminence was reinforced by a haughty internal culture and macho ethos. The litigators were particularly prone to swaggering and cockiness. Gray Cary lawyers tended to flaunt their elite status, and in turn were accorded deference by other lawyers and local judges. This social structure had been in place for so long that it was widely accepted—long after such vestiges had been eradicated in other cities. Those holding power and influence tend to zealously guard it, and often go to great lengths to preserve it.

When Dan left Gray Cary, which at the time was known primarily as a defense firm, he opened a solo practice specializing in suing doctors for medical malpractice. Dan’s medical degree made him well equipped to handle such cases. In some markets, plaintiff’s lawyers are held in low esteem by corporate law firms, but this was not true in San Diego. Elite personal injury lawyers able to win seven figure (or higher) verdicts were revered as celebrities. For one thing, contingent fee arrangements made successful plaintiff’s lawyers fantastically rich. One of Rudi Brewster’s proteges at Gray Cary, Dennis Schoville, left the firm to specialize in plaintiffs’ cases. Dan was one of several high-profile plaintiff’s lawyers in town who were regarded as rock stars. (The fact that he was generous with his friends and hosted lavish parties didn’t hurt.)

For example, Dan was elected to the Board of Directors of the San Diego County Bar Association and one year (1987) served as President of the SDCBA, indicating his popularity and esteem within the legal community. State court judges presided over the bulk of personal injury lawsuits in San Diego. Just as many defense lawyers secretly cheered for the plaintiff’s bar (in litigation and on the dance floor, it takes two to tango), trial court judges enjoyed the drama and prestige-by-association of being part of the “inner circle.” The relationship between trial lawyer and trial judge is symbiotic; favorable rulings by the trial judge can ensure jury verdicts and large damage awards in favor of the plaintiff–or at least greatly increase the prospects of victory.

Conflicts of interest and even outright corruption by judges in San Diego were not uncommon. It was widely known that Magistrate Judge Harry McCue, whose duties included conducting settlement conferences in federal securities lawsuits, served as a de facto “wing man” for class action mogul Bill Lerach, whose law firm was based in San Diego. Until he was sentenced to prison and disbarred for obstruction of justice and lying under oath, Lerach made hundreds of millions of dollars in settlements, many of them facilitated by McCue.

The state court bench was even more corrupt. Several trial judges, including the former presiding judge of the superior court, were convicted of corruption—taking bribes, peddling influence, and the like in a scandal centering on attorney Patrick Frega: Michael Greer, G. Dennis Adams, and James Malkus. This was just the tip of the iceberg. Other judges who were overly cozy with local plaintiff’s lawyers managed to avoid criminal charges and received a slap on the wrist on the form of reprimands from judicial ethics panels. For example, San Diego Superior Court Judge Vincent DiFiglia was publicly admonished for failing to disclose his close personal relationship with—and receipt of economic favors from—an attorney in a case in whose favor he ruled. DiFiglia resigned from the bench but went on to a lucrative career conducting private mediations and arbitrations. Other judges skated away without consequences.

Of course, this doesn’t necessarily mean that Betty Broderick was the victim of a corrupt scheme, or that her conspiratorial worldview was well-founded. She is portrayed in the Netflix series as a troubled, angry woman prone to vindictive, counter-productive actions. But neither is her ex-husband presented as a paragon of virtue. He comes across as a narcissistic, controlling, manipulative deceiver. When Betty (correctly, it turns out) suspected that Dan was having an affair with his much-younger former receptionist (whom he promoted to be his legal assistant despite her lack of any relevant experience or even typing ability), he cruelly denied it, calling Betty’s suspicions “crazy.” Psychologists call this “gaslighting,” and it is a form of emotional abuse. (Committing a double homicide is inexcusable under any circumstances, and I don’t mean to suggest otherwise.)

In San Diego’s legal community, however, Dan Broderick is regarded as a martyred saint. The largest meeting room at the headquarters of the San Diego County Bar Association is named the Dan Broderick Room, in his honor. Each year several San Diego bar organizations for local litigators present the “Daniel T. Broderick III Award” to “an accomplished trial lawyer who adheres to the highest standards of civility, integrity, and professionalism.” It is the most coveted award a San Diego trial lawyer can receive. It represents the pinnacle of achievement for an insider—the ultimate badge of Old Guard status.

Viewers of season 2—The Betty Broderick Story—can decide for themselves whether Dan Broderick was a saint, and whether his legacy warrants the encomium his acolytes continue to devote to him.