Trouble in Paradise? (Part 10)

The Future of Blount County: Further Thoughts on Growth, Land Use, and the Role of Sewer Connections

The recent controversy in Blount County regarding proposed subdivisions at Pate Farm and Best Farm focused public attention on the topic of managing the area’s future growth. According to the 2020 Census, Blount County now has 135,280 residents, an increase of almost 30,000 people since 2000—and an increase of nearly 50,000 people since 1990. Blount County’s population has more than doubled in the past 50 years. Most of the recent growth has occurred within the municipalities of Alcoa and Maryville (and, primarily as a result of annexation, in Louisville). Alcoa’s population grew almost 30 percent in the past decade, from 8,449 to 10,978, nearly twice the rate of Maryville. (With a population of 31,907, Maryville remains the largest city in Blount County by a wide margin.) As the incorporated areas reach maximum development (or become “built out”), pressure is increasingly placed on the unincorporated parts of the county—much of which is farmland.

Fear of overdevelopment has ignited a passionate response by Blount County residents from all walks of life, and across the political aisle.

The public is understandably reluctant to see picturesque farms developed into dense tract subdivisions, and much of the county is serviced by narrow, winding two-lane roads barely adequate for current traffic levels. Growth is inevitable—and necessary—but it must be managed in a responsible manner, so that infrastructure (schools, roads, drainage, utilities, hospitals) is not overwhelmed, and the community is not blighted with congestion, unsightly development, and urban sprawl. Blount County has a rural character and scenic beauty that can and should be preserved. Blount County residents, already facing at least three massive Amazon warehouses no one asked for or wants, are understandably leery of reckless overdevelopment.

Elected officials’ response to future growth is a major political issue that may become pivotal in the upcoming 2022 elections.

In an attempt to resolve concerns I had publicly expressed regarding the role of city sewer connections at Pate Farm and Best Farm, I met with Maryville City Manager Greg McClain on Tuesday, September 28, and had an informative meeting. What I learned during that meeting, and in preparation for it, is that land use is a complicated issue, and there are no “simple” solutions. Some of my previous views were based on incomplete knowledge of the relevant facts, and need to be revised. I summarize what I have learned below. My (revised) conclusions based on this information appear throughout and are reiterated at the end.[*]

1. Sewer Connections. The sewer system operated by the City of Maryville is—unlike some other city services—not exclusive to the City of Maryville. The sewer system is officially known as the “Maryville Regional Wastewater Treatment Plant.” While it is owned by the City of Maryville, it also services residents of the City of Alcoa and the Knox Chapman Utility District (and certain adjacent areas, as described below). In the 1970s, at the direction of the Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation (TDEC), Maryville and Alcoa replaced their separate sewer systems with a new “regional” plant, which is located near the Little River in Alcoa. The plant currently has around 22,000 customers (around 15,000 of which are in Maryville), using about half of the plant’s treatment capacity of 17 million gallons per day (MGD).

Because the sewer system was built as a “regional” plant, the City of Maryville has, pursuant to city policy [1], allowed connections to the system by property owners within the city limits and the surrounding “Urban Growth Boundary” (a concept explained in #3 below). City staff grants requests for sewer connections by property owners within the service area as long as they meet the city’s technical requirements. The pipe lines are installed at the property owners’ (or developers’) expense, and become the property of the city once installed. The city’s utility department does not review connection requests within the Urban Growth Boundary from a land use standpoint; Blount County is solely responsible for zoning and land use decisions outside of the city limits.

Thus, if the physical limitations of septic systems and/or applicable land use rules require a lower density for residential projects using septic than is required for projects connected to sewer, the difference in density is not determined or “approved” by the City of Maryville Water and Sewer Department. The city utility staff simply determine whether (a) the applicant is in the service area and (b) the request meets the technical specifications set by the city. Because the city’s established policy is to connect to properties in the Urban Growth Boundary (subject to meeting technical requirements and the property owner bearing the cost of connection), the appropriate way to reduce the scale of such extra-territorial connections is to reduce the footprint of the Urban Growth Boundary.[2] The appropriate way to reduce density in the UGB (and beyond) is to impose density limits in those areas to correspond with the available infrastructure. (Changing the existing zoning may be legally problematic.)

Due to the interrelationship of the various governmental entities in Blount County, any discussion of land use and zoning must take into account all of their respective roles and interests. It is truly an interdisciplinary subject requiring coordination among various entities and departments: utilities, schools, roads, public safety, planning, zoning, etc.

2. Sewer Funding. The City of Maryville endeavors to make the sewer system financially self-supporting based on fees charged to customers for sewer services. The city operates the sewer system as a “business-type activity” and tracks the revenues and expenses generated by the sewer system via an “enterprise fund.” City water and electricity utilities are treated in the same manner. According to the most recent Comprehensive Annual Financial Report (CAFR) for the City of Maryville (for the FY ended June 30, 2020), the Water and Sewer Fund had a positive cash flow, i.e., revenues exceeded expenses. Sewer plants are very expensive to build, upgrade, and expand. Capital requirements for such projects typically require borrowing large amounts of money. The Maryville sewer system is no exception. The original construction and a significant upgrade/expansion in 2010 (at a cost of over $32 million) were financed by revenue bonds. According to the CAFR, “These revenue bonds, while carrying the credit support of the City’s general obligation pledge, are repaid from net revenues of the appropriate utility.”

Certain improvements to the sewage treatment plant approved by the City Council in August 2021 (an $8.5 million project to install a new belt press and ultraviolet light water-purifying system) will be paid for using federal stimulus funds, according to McClain.

While I am concerned that Maryville property owners paying city property taxes should not be subsidizing sewer services provided to customers outside the city limits, based on my understanding (and McClain’s assurances), I do not believe this is happening. I wonder whether sewer users outside of the city limits are charged at a higher rate than city residents, to reflect the debt risk borne by the city for the tens of millions of dollars in bonds used to finance the system. If not, the city may want to consider a two-tier rate structure for sewer service.[3]

3. Land Use Jargon. The concept of an “Urban Growth Boundary” (or UGB) is unfamiliar to many people, and is potentially confusing. What is it? In 1998, the state of Tennessee required all cities to formulate a growth plan, pursuant to Public Chapter 1101. The goal was to manage the state’s future growth conduct over the next 20 years without urban sprawl. Additional considerations were to eliminate annexation fights between incorporated cities vying for same area. (Annexation, which used to be very permissive on the part of cities, is now more difficult because approval of the acquired area is required.) The creation of UGBs (which were envisioned as a “sphere of influence” with respective to which the designated city had an interest for purposes of future growth) also sought to eliminate the incorporation of new small cities that would complicate inter-governmental planning. This, too, is no longer an issue in Tennessee.

The stated purpose of an UGB is to “identify territory [contiguous to the existing boundaries of the municipality] that is reasonably compact yet sufficiently large to accommodate residential and nonresidential growth projected to occur during the next twenty years.” The UGB is territory in which the municipality can more efficiently and effectively provide urban services. The UGB is intended to limit urban sprawl and thereby limit the “impact to agricultural lands, forests, recreational areas and wildlife management areas” [TCA 6-58-106]. A municipality can only annex land that is in the UGB [TCA 6-58-111].

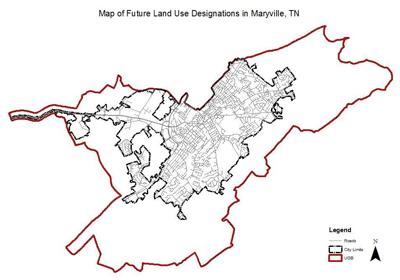

The UGB surrounding Maryville is an area measuring approximately 29.65 square miles contiguous to, and surrounding the city limits (which comprise approximately 16.8 square miles). In other words, Maryville has an UGB almost twice as big as the city’s footprint itself. The City of Alcoa also has its own UGB, as did the City of Louisville.[4] Does the label “UGB” serve any useful purpose? This is a fair question.

Maryville’s UGB is subject to county regulation because, despite its designation as a UGB, it is outside of the city limits and is therefore part of the county. (Maryville used to engage in land use planning in the UGB but eventually ceded that authority exclusively to the county.) Permissible land use in the UGB is now determined solely by the Blount County authorities (Planning Commission, County Commission, zoning board, etc.). As we shall see, this renders the concept of a UGB largely moot.

The majority of Maryville’s UGB is zoned, by the county, as “Suburbanizing District.” The purpose of the Suburbanizing District is to “regulate suburbanizing development of expected high to moderate density around the cities of Alcoa and Maryville” [Blount Co. Zoning Regulations, September 1, 2006, Section 9.1]. The second most common county zoning in Maryville’s UGB is Rural District 1, which is intended to “regulate rural development of expected moderate to low density within the county” [Blount Co. Zoning Regulations, September 1, 2006, Section 9.2]. The third most common county zoning in Maryville’s UGB is Commercial, which is intended to regulate commercial and other development of high to medium density around the cities of Alcoa and Maryville.

Pate Farm and Best Farm were both zoned “Suburbanizing District” some 20 years ago. Many residents opposed to the subdivisions proposed on that land were shocked to learn this recently.

In any event, returning to the topic of how the UGBs were formed over 20 years ago, Public Chapter 1101 required Blount County to form a Coordinating Committee. The Coordinating Committee included representatives from all the cities, the county, the school system, and other stakeholders. John Lamb, who was the Director of Planning for Blount County during the period that the county formulated its growth plan pursuant to Public Chapter 1101 (roughly September 1998 to July 2000), wrote a lengthy article in October 2000 summarizing the process. He explains:

The growth plan process was intended to bring all governmental parties to the same table for a cooperative effort. Also included at the table were selected representatives from various interests, including school systems, utility providers, homeowners, developers, farmers and conservationists. The Coordinating Committee, made up of these members, was to formulate a growth plan for the county, to then be acted upon by each local legislative body within the county. Each legislative body had power of veto over the plan…. Although other interests came to the table in the process, the major players were municipal and county governments….

The total membership of the Coordinating Committee was 16. Of this number, eight were directly associated with municipal governments – two from the largest city of Maryville, two from the next largest city of Alcoa, and four representing the four small towns. Only two members were directly associated with county government. The Maryville appointment of the planning commission member may be seen as being associated with both city and county governments. The remainder were nominally independent. The county government was thus a distinct minority in representation on the Coordinating Committee.

The planning process of the Coordinating Committee was characterized at times by inter-jurisdictional rivalries, bickering, political alliances, varying projections of future growth, and other considerations. The future growth projections made by Blount County (estimating a population of 136,000 in 2020) turned out to be eerily accurate. In general, the incorporated cities requested larger UGBs than made practical sense, to give themselves buffer zones and to ward off aggressive annexation from neighboring cities. Maryville was no different. As John Lamb explains, Maryville

initially identified an Urban Growth Boundary encompassing 69 square miles. The County did not accept such a large UGB. The area of the UGB then became a moving target, as the city grappled with both the county objections and internal discussions within the city government on the role of growth for the city….

The city had undertaken a citizen participation-based planning process in the recent past, which was ongoing during the 1101 process. Results of that general planning process indicated that most city residents did not want the city to grow too fast, and that keeping the small town character of the city was very important. One of the major concepts fueling the internal discussions was the wish to have only one high school. To do this with just expansion of the existing high school obviously limited the expectation for population growth. The city government also discussed how growth of the city would impact costs of expanding urban services. The conclusion was that the city should not grow at a rate that would overwhelm the ability to provide schools and other urban services. The city even considered a moratorium on annexation and a limit on new building permits for the near future.

Maryville began a process of chipping away at its initial 69 square mile UGB with a series of proposals which ultimately resulted in a UGB proposal encompassing about 32 square miles. The main argument for such an extensive UGB was that the “city would need to be there for development.”

The County recognized that Maryville would probably need to grow by about 5.3 square miles to account for expected population projections. The County accepted that uncertainty in addressing market forces would require a “cushion” of area to more reasonably address growth. The county thus accepted an area of 15.4 square miles as an appropriate area for an Urban Growth Boundary for the City of Maryville, being almost three times the minimum based on population projections. This acceptance of a generous market factor of greater than 100 percent went beyond what most of the planning literature indicated (see above under discussion for Alcoa). The County rejected the 32 square mile UGB proposal by the city and ultimately approved by the Coordinating Committee. (Emphasis added.)

As can be seen, the establishment of the UGBs some 20 years ago was based on a good deal of posturing, skirmishing, and old-fashioned horse-trading. Initially, the county was opposed to the concept of UGBs and the County Commission was inclined “to reject any UGB and to take an initial stance of no urban growth.” The county and the Coordinating Committee reached an impasse, resulting in the county’s rejection of the Committee’s proposed plan. The county had to resort to its own planning process. The county ultimately adopted its own growth plan, albeit conceding that “The 1101 Growth Plan did not embody much planning.” As John Lamb explains,

The County formally initiated the first county-wide planning process in more than 20 years with resolution and support of the County Legislative Body in April of 1996. The County pursued the process with population analysis, population projections, analysis of physical factors of development, analysis of development patterns, reliance on a process with strong citizen input, and participation by the County Commission as final decision makers.

In early 1997, the County undertook 17 citizen input workshops at different sites throughout the county, including three sites in the cities. About 250 citizens participated in identifying an agenda for policy consideration by answering two basic questions: what is good about Blount County that should be preserved in the future, and what needs to be changed in Blount County to make a better future? The results of the first round of citizen input were reported back to the same 17 sites in late 1997, and about 450 citizens participated in refining a set of policy and implementation options. The policy options were further refined, with specific attention to implementation, by a select 11 member Citizen Advisory Committee from July of 1998 to January of 1999.

The results of all citizen input workshops and a report by the Advisory Committee were considered by the Blount County Planning Commission. The Planning Commission produced and approved a Blount County Policies Plan in June of 1999, with a 21 item implementation agenda. One of the implementation items was to formulate a growth plan as required by Public Chapter 1101. [I have not reviewed this 1999 document.]

To make a long story short(er), the current UGBs were drawn 20 years ago amidst political jockeying and discord. John Lamb is very critical of the Coordinating Committee:

The Coordinating Committee operated in a manner not conducive to citizen input. No effort was made by the Committee to formally involve the general citizenry in deliberations. The only points of citizen input were the required formal public hearings on the separate plans of the county and municipalities, and the overall plan of the Coordinating Committee. These public hearings were not well attended, and in any event came after the plans were formulated.

In addition, some of the Committee members advocated that municipal and county legislators should not be involved in the early process. The reason given for this resistance to legislative inclusion was that positions needed to be flexible in the early stages of the process, and involvement of legislative representatives would lead to a hardening of positions and an infusion of unneeded politics. The County rejected this stance and included continuous consultation at several levels with County Commissioners….

The Public Chapter 1101 process itself was misconceived. John Lamb concludes that

From the standpoint of Blount County, the Public Chapter 1101 process was less than satisfactory.

The membership of the Coordinating Committee mandated by the 1101 law was stacked in favor of municipal interests, to the distinct disadvantage in addressing legitimate County concerns.

The law did not provide a sound basis for judging the reasonableness of proposals for growth areas. The municipalities were thus not constrained by a consistently identifiable set of standards in identifying Urban Growth Boundaries.

The 1101 law put the County and the six municipalities into conflict over identifying territories. This was not conducive to cooperative and rational planning.

The 1101 law ignored existing planning legislation that could provide a more comprehensive approach to growth planning. The 1101 process was not inclusive. There was little citizen input, and local legislative decision makers were not adequately included in deliberations.

The 1101 law did not have clear land use and development criteria for determining sprawl and appropriate development patterns. Status quo development patterns were projected into the future.

The point of this post-mortem is to demonstrate that the establishment of the UGBs over 20 years ago was somewhat arbitrary, haphazard, and marred by a contentious, politicized process. The very concept of UGBs was arguably flawed. Twenty years have passed. Many things have changed since the enactment of Public Chapter 1101, including the laws regulating annexation. As a practical matter, annexation is no longer possible. Maryville no longer exercises land use planning authority over the UGB. For all these reasons, the current UGBs should not be regarded as “holy writ” or carved in stone.

In 2021, growth management in the county outside of the city limits should revisited in a comprehensive manner.

4. Managing Future Growth. It is time to take a fresh look at projected growth in Blount County, and to review land use plans based on actual and projected growth. The recently-formed Ad Hoc Committee [5] may face difficulties in undertaking such a review. Revising the UGBs is a cumbersome process. As one commentator has stated:

Making even small amendments to growth plans can be cumbersome. If a single city wants to retract its urban growth boundary for whatever reason, the entire coordinating committee has to be convened and two public hearings must be held. To simplify the process where only a single city is affected, cities should be allowed to retract their growth boundaries without approval from other members of their coordinating committees, but only where the boundary abuts a rural or planned growth area and only after giving notice to the county and to residents of the area and holding a public hearing. The affected county should then decide whether to include the removed area in the adjoining rural or planned growth area or to designate a new planned growth area, and the proposed change should be presented to the state’s Local Government Planning Advisory Committee for approval.

Blount County’s growth plan should be revisited. As stated by the Tennessee Advisory Commission on Intergovernmental Relations,

Growth plans were first adopted 15 years ago and were based on 20-year projections that have since become outdated. Not only are they old, but the economic recession has fundamentally changed growth patterns in many areas. Actual growth and development in some counties has [sic] lagged projections and in other places far exceeded them. This is certain to happen again.

Consequently, any plan not revisited in the last few years is likely to be outdated. The legislature should require all counties to reconvene their coordinating committees and review their growth plans before a certain date and revise or readopt them and repeat this process at regular intervals or as circumstances require. (Emphasis added.) [6]

5. Conclusion. I’m not a land use expert and don’t have the perfect solution to address the many challenges presented by Blount County’s future growth. Unfortunately, there is no “silver bullet.” I have learned, however, that denying sewer connections to property located outside of the City of Maryville (but within its UGB) is not the answer. The UGB surrounding Maryville must be reduced in size (which would have the effect of reducing the area serviced by Maryville’s sewer system); the minimum lot size for subdivisions in the UGB needs to be increased even for houses connected to the sewer (one acre minimum for septic and half-acre lots for sewer is a reasonable benchmark); subdivision rules should require developers to demonstrate that the existing infrastructure is adequate; and the Ad Hoc Committee should review the overall zoning and regulatory scheme to make sure that future growth is managed responsibly. This review will take far longer than 90 days and must involve participation by the general public.

The goal for the future, as it has been in the past, is to grow without destroying Blount County’s unique character, overwhelming the existing infrastructure, or imposing additional costs (in the form of increased property taxes) on existing residents. A growth plan commissioned by Blount County in 2005, entitled The Blount County Growth Strategy, prepared by the consulting firm Hunter Interests Inc., identified the key factors that must be considered:

Guiding Policy 1: The rural, small town, and natural character of the County should be preserved. [7]

Guiding Policy 2: Land use and development should be managed and regulated to preserve the quality of our growing County.

Guiding Policy 3: The guiding policy in any government actions in relation to the use and development of land should be to limit regulations to specific public health, safety, and welfare objectives, balanced with responsible freedom in the use of the land.

Guiding Policy 4: County roads should be improved and maintained to serve existing and future development.

Guiding Policy 5: Growth and development should be matched with provision of adequate infrastructure such as utilities, roads, and schools.

The first policy should represent the top priority for all future land use planning. The 2005 growth strategy document should be the starting place for the Ad Hoc Committee’s review of existing land use methods. The existing subdivision rules state that “land shall not be subdivided until available public facilities and improvements exist and proper provision has been made for drainage, water, sewerage, and capital improvements such as schools, parks, recreation facilities, transportation facilities, roads and other improvements.” The existing rules also state that the goal is “To preserve the natural beauty and topography of the County and to insure appropriate development with regard to these natural features.”

Blount County residents must be assured that these objectives will be served by the Blount County Planning Commission. Serious consideration should be given to reducing the size of the existing UGB around Maryville. To the extent possible, farmland in the county outside of the UGB should remain rural and not be zoned for residential development.

Footnotes

* I compiled this information in good faith, and am willing to supplement and/or correct it in response to additional information. Suggestions are welcome.

1. Water and Sewer Department Rules, Regulations, and Policies (2019), Section 1.9, approved by the Maryville City Council in Resolution #2019-22.

2. Accordingly, my concerns about the city’s grant of a sewer connection to Pate Farm and Best Farm on the grounds that this was unauthorized or irregular were misplaced. Mea culpa. I continue to have concerns about the manner in which the easement request was handled by the county. Pate Farm proposed to connect to the sewer line servicing the Carpenter Middle School. The pipeline was on land owned by the county. An easement request was made to the Blount County Board of Education, which referred the matter to the BOE’s Facility Committee. The Facilities Committee recommended approval of the request but lacked the authority to approve it because the property in question is owned by the county. The recommendation was forwarded to Mayor Ed Mitchell, who later approved the easement, possibly without County Commission approval. The processing of the easement request lacked transparency and was apparently handled in an ad hoc manner.

3. It appears that the city charges a higher rate for water service outside of the city limits.

4. Louisville has annexed all the land within its UGB, rendering it moot. The entire area is now within the Louisville city limits.

5. The Ad Hoc Committee was formed by a resolution (No. 21-09-019) of the Blount County Planning Commission, authorized “to study the zoning and subdivision regulations.”

6. The City of Townsend undertook such a review in 2010, producing a Land Use and Transportation Plan 2010-2020.

7. The report elaborates:

This Guiding Policy represents perhaps the core value of the community as expressed in public forums, planning and policy documents, media coverage of the growth issue, and a historical connection to Blount County’s agrarian past. It is also closely linked to the cultural and economic foundation represented by the Great Smoky Mountain State Park and the experience associated with its visitation.

This Guiding Policy is directed at a combination of County assets and resources including the Little River Watershed, active farming land, mountainsides and ridge tops, wooded lands, wetlands, and just plain open space. Scale of development is also an embedded element of the Policy, as should be design considerations and other factors. (Emphasis added.)