Who Created the “Diversity” Monster?: How Republican Supreme Court Justices Gave Us Affirmative Action

The U.S. Supreme Court started down the slippery slope of racial preferences in 1978, with baleful consequences.

This essay first appeared in the March/April 2022 issue of Chronicles magazine (here). Thanks to Real Clear Policy and Real Clear Books (here)!

Scholars increasingly treat the issue of race with kid gloves. As the cancel culture accelerates, race—always a sensitive topic—has become nearly taboo. Any serious exploration of the correlation of intelligence and race is met with denunciations of racism, as Charles Murray can attest. Murray’s 1994 magnum opus, The Bell Curve, co-authored by Richard Herrnstein, was met with hysterical criticism from the left, earning him the label “extremist” by the demagogic Southern Poverty Law Center. To the leftists who dominate academia, racial disparities in crime statistics, economic performance, academic achievement, and school discipline admit of only one permissible explanation—systemic racism.

Yet intrepid scholars have (at least for the time being) been able to talk about how affirmative action in higher education—preferential admissions favoring blacks and Hispanics—hurts the very groups those policies were intended to benefit. Richard Sander and Stuart Taylor addressed this subject in 2012 with their powerful book Mismatch. The data, they argued, show that giving minority students an artificial boost into higher-echelon universities actually hurts their long-term prospects compared to similarly-qualified students attending schools to which they were admitted without preferences. “Mismatched” students learn less, earn lower grades, and gravitate away from rigorous STEM majors to “easier” disciplines in the social sciences and humanities.

Not everyone agrees with the “mismatch” argument, obviously, but Sander and Taylor were not condemned as racists for simply talking about it. (The late Justice Antonin Scalia was criticized for asking a question premised on the mismatch thesis at oral argument in the Fisher v. University of Texas case in 2015.) Perhaps the left’s grudging tolerance for the mismatch argument is due to the fact that, even in today’s overheated political culture, most Americans adhere to the ideal of race neutrality in college admissions (as evidenced by the recent defeat of Proposition 16 in California, which sought to repeal Proposition 209, that state’s 1996 ban on racial preferences). Perhaps also the deleterious effect of racial preferences is considered an acceptable topic because it highlights the recipient of preferences—as opposed to those in disfavored groups discriminated against—as a “victim” group. Data showing that blacks do not benefit from—and are harmed by–preferential admissions are not easily characterized as “racist.”

A recent book, A Dubious Expediency (subtitled “How Race Preferences Damage Higher Education”), examines racial preferences in higher education (sometimes euphemistically called “affirmative action”) from a broader perspective than did Mismatch. Accordingly, it may receive a more hostile reception than Mismatch—or be ignored altogether. Edited by two law professors at the University of San Diego—one of whom, Gail Heriot, is also a member of the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights—the book consists of a collection of essays by well-known critics of race discrimination in higher education, including Heather Mac Donald, author of The Diversity Delusion (2018); Peter Kirsanow (Heriot’s sole conservative colleague on the Commission); and Peter Wood, president of the National Association of Scholars.

The book is a deep dive into the topic of preferential admissions based on race and ethnicity: its origins and consequences, and the ancillary pathologies—multiculturalism, neo-segregation, intersectionality, and the like–it has spawned. It is not a pretty picture. Racial preferences are ultimately an assault on meritocracy—of the notion of excellence itself.

The title of the book is drawn from a quote by liberal jurist Stanley Mosk, who as a justice on the California Supreme Court wrote an opinion for the Court in 1976 overturning a racial quota system at the University of California-Davis’ medical school. A white applicant who was denied admission in favor of lesser-qualified minorities, an ex-Marine medic named Allan Bakke, sued to challenge the quota system. Bakke’s lawsuit alleged reverse racial discrimination–there were two different standards for admission: one for whites and one for minorities. Minorities were admitted with much lower grades and test scores than the cut-off for whites. Bakke was rejected even though he was better qualified than many blacks who were admitted.

Mosk’s opinion for the 6 to 1 majority—on a famously left-wing Court—held that racially discriminatory admissions policies are per se unconstitutional as a violation of the Fourteenth Amendment’s equal protection clause. Mosk’s opinion in Bakke said that allowing race discrimination in admissions to achieve racial balance “would call for the sacrifice of principle for the sake of dubious expediency.” The principle is color blindness and judging people on the basis of their individual merit. Counting by race, which Mosk derided as “dubious expediency,” is what leftists now exalt as “equity” or “anti-racism.” How things have changed. How did we get from an uncontroversial embrace of race neutrality in 1976 to the current “woke” preoccupation with “disparate results” and end-result equality? That is the important subject of A Dubious Expediency.

As a matter of constitutional law, the damage was entirely self-inflicted. In a landmark 1978 decision, the U.S. Supreme Court replaced the California Supreme Court’s blanket prohibition of race discrimination in Bakke with an amorphous ruling that, while forbidding racial quotas, allowed race to be considered in admissions to the extent deemed necessary to achieve a diverse student body. Bakke won admission to medical school, but so long as colleges are subtle enough to avoid explicit racial quotas, reverse discrimination could continue. Racial preferences would pass muster, as long as they were applied with subterfuge in a “holistic” admission process. Overnight, secrecy and dishonesty replaced candor and transparency in college admissions.

Following Bakke, affirmative action in admissions became de rigueur. The Court’s embrace of “diversity” as a justification for racial preferences has for decades allowed college admissions officers to discriminate against whites and Asians to achieve statistical goals that are de facto (if not explicit) quotas. Since 1978, millions of college students have “benefited” from racial preferences. They, along with the considerable bureaucracy—in academia and corporate America–required to administer “diversity” policies, have become an intensely-focused interest group committed to preserving racial preferences, despite the lack of any evidence that diversity qua diversity improves higher education (or any other sphere of life).

Big Business, having committed itself to HR policies and marketing strategies predicated on diversity, has a vested interest in imposing compliance on all companies—thereby creating a barrier to entry for competitors. Large corporations are among the most vociferous defenders of racial preferences.

Opponents of racial preferences in admissions have, subsequent to Bakke, unsuccessfully challenged their constitutionality in a series of high-profile cases involving the University of Michigan and the University of Texas. Most recently in 2016, the Supreme Court has stubbornly refused to abandon its fealty to “diversity.” The holding of Bakke, and the Court’s failure to overturn it for over 40 years, cannot be blamed solely on “liberal activists.” Numerous “conservative” justices appointed by various Republican presidents are complicit as well. The tortured opinion in Bakke was written by Republican-appointed Justice Lewis F. Powell. The most recent decision upholding “diversity”—in Fisher v. UT—was written by Republican-appointed Justice Anthony Kennedy.

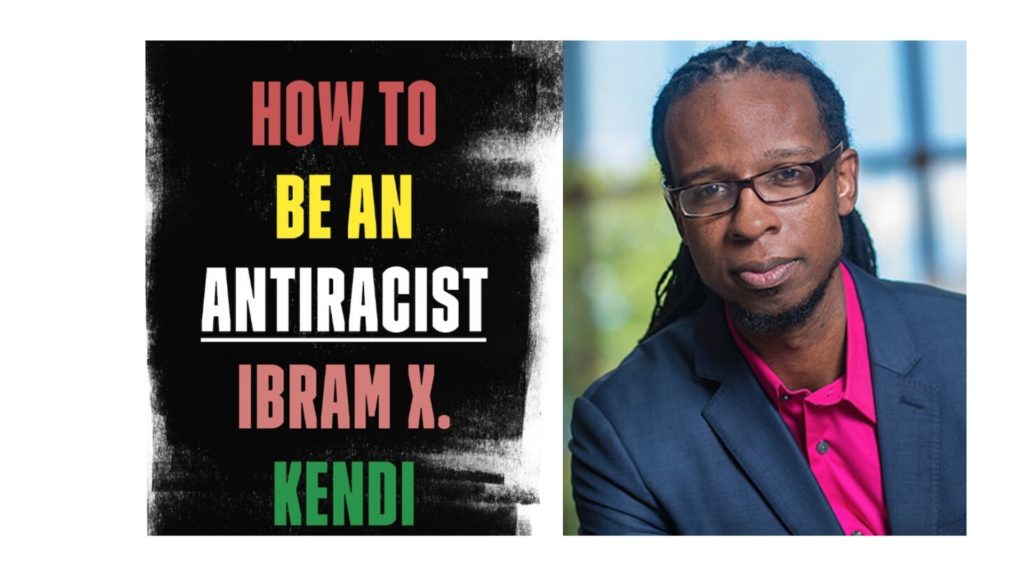

Prior to Bakke, the Burger Court (named after Chief Justice Warren Burger, appointed—like Powell–by President Richard Nixon) had recognized a legal doctrine that treated disparate racial outcomes in employment the same as intentional discrimination. The so-called “disparate impact” doctrine, unveiled in Griggs v. Duke Power Co. (1970), is an essential feature of the radical “anti-racism” ideology espoused by Ibram X. Kendi (born as Ibram Henry Rogers) and other proponents of critical race theory. Any aspect of American life in which blacks do not enjoy statistical parity with whites is evidence of racism, they claim, and must be rectified by government intervention.

Many critics trace the lineage of CRT back to the Frankfurt School, or Italian Marxist Antonio Gramsci, or radical Harvard law professor Derrick Bell, but the progenitor of the current preoccupation in higher education with “diversity, inclusion, and equity” is—ironically—a body of decisions issued by a Republican-dominated Supreme Court. As the essays that comprise A Dubious Legacy document in depressing detail, the fanciful bromides of “diversity” have contaminated not only higher education, but also the legal academy (and by extension the legal establishment), the workplace, Big Tech, the corporate media, philanthropy, Hollywood, and other institutions. As Peter Wood laments,

In practical application the pursuit of diversity has become a euphemism for thrusting race preferences into any and all decisions about how social goods—jobs, contracts, public funding, parades, TV shows, gigs, awards, political offices, and so on—should be distributed.

A Dubious Legacy, although written by lawyers and scholars, is not a tedious treatise or impenetrable legal brief. It is lively, accessible, and highly informative, with enough end notes to satisfy curious readers and a refreshing lack of the type of pseudo-intellectual jargon that typically pervades the genres of post-modernism and identity politics. The book provides a broad overview of a complex subject with a fair-minded treatment of its many facets. For example, the chapter by Lance Izumi and Rowena Itchon highlights the extent to which racial preferences particularly disadvantage high-achieving Asian-Americans, who would be significantly “over-represented” in colleges if admissions were based solely on merit.

The editors, Gail Heriot and Maimon Schwarzschild, suggest in the Introduction that Justice Neil Gorsuch’s hyper-textualist interpretation of Title VII in Bostock v. Clayton County (2020)—construing the statutory prohibition of discrimination based on “sex” to include “sexual orientation” and “gender identity”—may portend a heightened scrutiny by the Court of racial preferences in the future. I wouldn’t hold my breath. The die is cast: Diversity now, diversity tomorrow, diversity forever.