The Lawyers’ War on Law

This essay originally appeared in the pre-digital magazine The American Enterprise (published by the American Enterprise Institute) in March 2001. Written over 21 years ago in the wake of the 2000 election dispute in Florida, which was resolved in Bush v. Gore, I think my take has held up pretty well. Proven prescient, even. Thanks to Instapundit (here)!

It didn’t end with Florida.

Now that the 2000 presidential contest is finally over, let’s try to figure out how we reached the point where national elections are determined by a cadre of lawyers and judges. And more importantly, how we can restore the rule of law not only in elections but in all of American life.

For five long weeks after the election was–or should have been–concluded, the country was paralyzed by a flood of lawsuits challenging George W. Bush’s narrow victory in Florida. As teams of lawyers raced from one courtroom to another, the presidency was up in the air.

Then, following a unanimous remand from the U.S. Supreme Court, plus Judge Sanders Sauls’ rejection of Gore’s election contest, and unambiguous rulings from two circuit courts on the absentee ballot challenges in Seminole and Martin counties, the whole affair seemed on the brink of resolution.

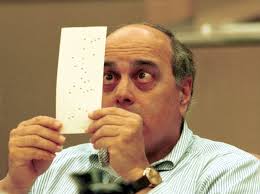

Those hopes were dashed on December 8, when a sharply-divided Florida Supreme Court plunged the country further into confusion by a wholesale re-writing of the Florida election laws and an order to selectively hand count certain ballots, with no uniform standard on whether “dimpled chads” should be counted as votes. Fortunately, the U.S. Supreme Court ended the crisis when it stayed the recount on the next day, and issued its ruling in Bush v. Gore on December 12.

Several grim lessons emerge from this affair. First, it was a very close call. Al Gore and his lawyers almost succeeded in overturning the results of a presidential election, even though Gore had no case. The irreducible fact is that Bush received more votes than Gore in Florida, even including felons and excluding many military absentee ballots. The only chance Gore ever had was to convince a Democrat-controlled county canvassing board or court to count non-votes (that is, dimpled chads) as Gore votes. And he nearly got away with it.

How close was it? Bush v. Gore was decided by a 7-2 vote, but the U.S. Supremes split 5-4 on the remedy. The switch of a single vote would have sent the recount back to the Florida Supreme Court, which would have gone to any length to rule in favor of Gore. Legal journalist Stuart Taylor (who “has never voted for a Republican” for President) accused the Florida high court of “trying to reverse the outcome of a presidential election by rewriting the vote-counting rules.” Given another opportunity, the Florida Supreme Court might have succeeded. So Bush’s election victory in Florida, as determined by the initial count, a mandatory machine recount, and a subsequent manual recount, was ultimately upheld by a single judge.

Why do I say Gore had no case? Consider the admissions made by Gore’s legal team in the U.S. Supreme Court: The counsel for Florida’s Attorney General conceded that a manual recount had never previously been ordered in a Florida election solely because some voters allegedly failed to punch the ballot card cleanly, as directed in the written instructions. Voter error, in other words, had never been recognized as a ground for an election contest–until this case. Even more damning, Gore’s counsel had to concede, in response to a question by Justice Kennedy, that the Florida legislature would have violated the federal safe harbor statute if, after the election, it had extended the deadline for the secretary of state to certify election results–as the Florida Supreme Court did.

If you wonder how a litigant can win a lawsuit without any supporting facts or law, as Al Gore almost did, you haven’t been paying attention to what’s been happening in our justice system over the past few decades. Like a juggernaut, trial lawyers have cut a swath through corporate America, plundering and sometimes destroying entire industries, such as the asbestos industry, silicone producers, breast-implant makers, pharmaceutical companies, the tobacco industry, gun manufacturers, and soon HMOs, tire manufacturers, and the lead paint industry. These lawsuits succeed without credible proof of injury or causation–“junk science” experts, paid by the hour, provide whatever pretext a jury requires–because of a combination of judge-made liability rules that tilt the playing field in favor of plaintiffs’ gripes, trial judges determined to redistribute wealth, and the brute force of endless dishonest lawsuits that seek unlimited, bankruptcy-threatening damages. Many businesses, having lost faith in courts’ ability or willingness to make rational rulings, routinely pay the equivalent of ransom just to escape the system. Most ominously, the trial lawyers have recently joined forces with state and local governments to loot unpopular industries for political purposes. Litigation is no longer just a way to bilk opponents; it is a political weapon.

The second, related lesson is that the crisis in Florida was the culmination of several trends in law and politics over the past 50 years. The immediate antecedents of the 2000 election are the Clinton impeachment fight and the O.J. Simpson criminal trial. We are witnessing nothing less than a lawless regime of, by, and for the lawyers. Just connect the dots:

* Changes in ethical, substantive, and procedural rules in recent decades have transformed lawyers from genteel members of a profession and “officers of the court”–supposedly engaged in the common pursuit of justice–into ruthless mercenaries who will resort to any tactic to win. The advent of attorney advertising, contingency-fee arrangements, class-action lawsuits, and the ability to engage in open-ended “discovery” (a/k/a, fishing expeditions) during litigation–all relatively recent developments–helped usher in the era of lawyer-as-hired-gun.

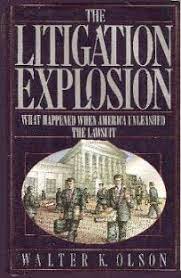

But the problem is not just the number of lawyers, or the power they wield. In the past, law was imbued with morality, and justice was conceived as a pursuit of truth. Not anymore. Now lawyers are ethically bound to “zealously represent” their clients and to advocate novel, far-fetched legal theories. Referring to the “reigning view of lawyers’ ethical responsibility” as “all gas pedal and no brake,” Walter Olson observes in his book The Litigation Explosion that “what we got … was a gangland war where the weaponry and tactics are varied and imaginative, spies are everywhere, all sorts of bystanders get mowed down, and the fighting continues around the clock for years. In the hope of getting justice, the American law deregulated combat.”

If lawyers are ethically bound to win at all costs, truth becomes an impediment to be overcome. The most effective litigation tactics become those that suppress, distort, or otherwise defeat the truth. The implicit conclusion is that lying–even under oath–is acceptable, if that is what it takes to win. Lawyers now routinely present lies to courts and juries. Many cases, and most defenses in criminal cases, rest entirely on lies: The Menendez brothers killed their parents in self-defense; O.J. Simpson couldn’t have killed his ex-wife because he was chipping golf balls in his front yard; Bill Clinton didn’t have sex with Monica Lewinsky; and a dimpled chad is a vote for Al Gore.

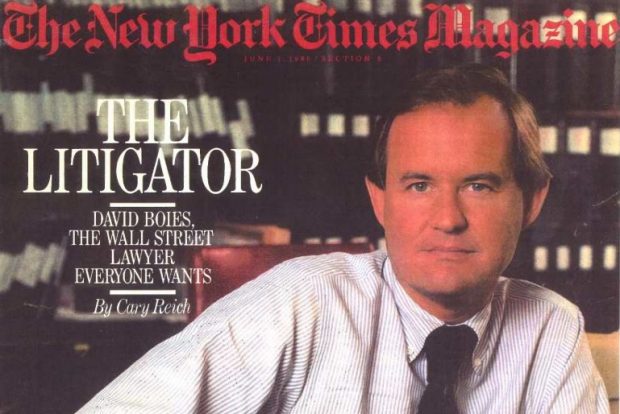

Consider that our most celebrated lawyers, in a culture that worships celebrity, are those who have succeeded in acquitting the obviously guilty (Johnnie Cochran, Alan Dershowitz, et al. and O.J. Simpson; David Kendall et al. and Bill Clinton); or punishing the innocent (David Boies vs. Microsoft). Indeed, the measure of these celebrities’ fame is determined by the degree to which they are able to triumph over the truth through cunning, trickery, and demagoguery.

For example, Al Gore’s much-hyped “superlawyer,” Mr. Boies, solicited and filed an affidavit in the Florida litigation that misrepresented the facts of an important Illinois case–which was relied on by the Florida Supreme Court in its infamous November 21 decision favoring Gore. The affidavit prepared by Boies claimed that an Illinois court conducting a recount had counted dimpled ballots as votes, but the facts were otherwise: Dimpled ballots were not counted. Even after this deception was exposed by the Chicago Tribune and the signer of the affidavit recanted, Boies did not withdraw the erroneous document or notify the court in Florida. At best, he violated the rules of practice in Florida by not correcting the record; at worst, he suborned perjury. In either case, he should be disciplined (if not disbarred), but instead he basks in praise and accolades. Based on his performance in Florida, the National Law Journal just honored Boies as one of its “Lawyers of the Year.” We have come a long way from the archetype of “Honest Abe,” the plainspoken country lawyer.

* The “politics of personal destruction”–demonizing one’s opponent through the Big Lie–has become a principal weapon of the Left in partisan politics and, as law and politics merge, in the battleground of activist litigation. The campaign of deceit that crushed the Supreme Court nomination of Robert Bork in 1987 gave birth to a new verb, “to be Borked.” Emboldened, the Democrats destroyed House Speaker Newt Gingrich and tried but failed to destroy Supreme Court nominee Clarence Thomas. Bill Clinton’s spin doctors used this ploy to smear Linda Tripp, Paula Jones, and, in particular, Ken Starr, and thereby helped Clinton win reelection in 1996 by demonizing Republicans to increase voter turnout among the African-American community. The O.J. defense team relied to a great degree on the personal vilification of policeman Mark Fuhrman. The trial lawyers have perfected this technique in their assaults on the tobacco, gun, and other industries. As law professor Robert Nagel puts it, “our courts have become places where the name-calling and exaggeration that mark the lower depths of our political debate are given a more acceptable, authoritative form.” Is it any wonder, then, that the Democrats and the media spewed venom at Florida election official Katherine Harris, or that Democratic operative Bob Beckel was doing “opposition research” on Republicans bound for the Electoral College?

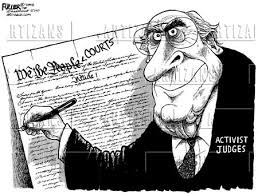

* The ascendancy of “legal realism”–a theory that assumes law has no fixed meaning but only represents prevailing views of what is socially desirable–unleashed a growing torrent of judicial activism in recent decades, aided by a revolution of liability rules. As a result of these developments, activist judges and predatory trial lawyers exercise unprecedented power. This largely unchecked power has further impaired whatever flimsy principles and scruples they had prior to attaining their present exalted status. As we’ve seen most recently in the actions of the trial lawyers who sit on the Florida Supreme Court, litigation now resembles a World Wrestling Federation tag team affair with the courtroom as the ring, except that the referee is really a participant in the fight.

Thus we had the spectacle of Florida’s seven activist justices unanimously, without invitation from either side in the lawsuit, forbidding an elected official (Katherine Harris) from complying with her legal duty to certify the election results within seven days, and then re-writing an unambiguous state law and overruling the factual findings of the trial court in the absence of any showing of error.

Such brazen manipulation of, or outright nullification of, controlling statutes, constitutional provisions, and judicial precedents in order to achieve the desired result is, unfortunately, commonplace. It happens every day in courtrooms, state and federal, throughout the country. The “rule of law” is in many respects a hollow phrase. Consider: A jury acquitted O.J. Simpson because the defense successfully urged them to disregard the judge’s instructions to the jury; Bill Clinton escaped impeachment because the Senate was unwilling to enforce the law; the tobacco settlement was in reality a coerced payoff in a legalized extortion scheme; and liberal pundits applaud the Florida Supreme Court for its transparent usurpation of executive and legislative powers.

* Finally, these outrages flourish all the more easily because they are praised by the “chattering classes”–the media, academia, and the legal profession–which have been captured by the Left. Indeed, it was difficult to distinguish news coverage from partisan flackery throughout the presidential campaign. The ferocity of the media’s antipathy toward Katherine Harris was truly breathtaking. Liberals, it seemed, despise her for the same reason they despise Ken Starr: she, too, takes the law seriously.

Why, then, did the army of unscrupulous lawyers filing a blizzard of baseless lawsuits, with a captive media cheerleading on the sidelines and the most liberal state supreme court in America presiding, not succeed in picking up 900-odd votes to win the last election? In a nutshell, Gore & Co. underestimated the resistance. Bush and his legal team fought back, hard, both in the courtroom and the court of public opinion. The rhetoric used by Bush and his spokesman James Baker was appropriately blunt. And the political establishment in Florida–Governor, Secretary of State, and both houses of the legislature, all Republican–fought back.

More importantly, the public had a direct stake in the outcome of the litigation, paid close attention to what was happening, and vigorously opposed the Gore team’s legal mayhem. This included noisy but well-behaved protests and the effective application of political pressure on elected officials. In addition, the litigation was necessarily limited: The December 12 deadline for appointing electors was an important factor in Bush’s favor. Finally, the U.S. Supreme Court stood up for the rule of law at a critical juncture, despite the prospect of inevitable attacks from the Left.

Though Republicans should celebrate Al Gore’s defeat, they would be wrong to think they have won any more than a battle. The Democrats (and their allies–the media, trial lawyers, and activist judges) will be back to fight another day.

The ultimate lesson? With lawyers and judges running elections, our liberties are as precarious as a hanging chad. To avoid being held hostage again, we must disarm the perpetrators through meaningful legal reform: adopt loser-pays rules for lawsuits, abolish the contingency fee, curtail liability rules, limit the award of punitive damages, control class-action abuses, and tighten up ethical rules to restore honor and decency to a profession that has lost its way. Judicial activism can be curbed by holding judges democratically accountable, through periodic retention elections, and removing rogue judges at election time (two of the Florida Supreme Court Justices will be on the ballot in 2002). The executive and legislative branches should reclaim the prerogatives that have been surrendered to or usurped by the judicial branch. And we the public must remember what it feels like to engage in combat with a remorseless enemy, because the fight has just begun.

Mark S. Pulliam, a San Diego attorney, is legal correspondent for the California Political Review.