Our Fractious Discourse

This essay originally appeared in the Daily Times on February 2, 2023 (here). Thanks to the Tennessee Conservative News (here)!

There is a common belief, frequently asserted with grave concern, that our public discourse has become overly fractious—that is to say, disagreeable. The implicit premise of this sentiment is that man’s natural demeanor—prior to a more recent coarsening of manners often blamed on partisan politics–is to be kind, respectful, and considerate of others. Chirpy nags suggest that the model of civility to which Americans should aspire is singing Kumbaya around the campfire. To paraphrase Rodney King, namesake of the deadly 1992 riots in Los Angeles that saw the City of Angels go up in flames, “Can‘t we all get along?”

In a word, No. Americans have always been a contentious, opinionated bunch, and the rhetorical climate in 2023, while far from ideal, is consistent with earlier periods in our history. Let’s begin with the human condition itself, a “state of nature” that the English philosopher Thomas Hobbes described as “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.” The most we can expect from civil society is peaceful coexistence among men, not utopian harmony.

The early American settlers fled Europe because they sought religious freedom, but the various sects were not particularly tolerant of one another upon arrival in the New World. Puritans, Quakers, Catholics, Anglicans, and other Protestant denominations established different colonies because of strongly-held differences among themselves in belief and practice. In the colonial period, there were also profound conflicts between those loyal to the British Crown (Tories, or “Loyalists”) and those who supported independence (so-called Patriots). Sometimes this conflict divided family members.

Even among Patriots, discourse was often fractious. Not even George Washington, the beloved “Father of Our Country,” was immune from backbiting and recrimination. While the Revolutionary War was underway, a group of senior Continental Army officers (the “Conway Cabal”) plotted to replace Washington as commander in chief with General Horatio Gates. After the war, the Founding Fathers had to suppress armed insurrections by rebellious farmers opposed to paying taxes (Shay’s Rebellion; the Whiskey Rebellion).

When it came time to adopt the Constitution drafted in 1787, the young nation was fiercely divided between those supporting ratification and so-called Anti-Federalists, who were opposed. Later, partisan disputes between the two dominant political parties—the Federalists and the Democratic-Republicans—were vicious and protracted, making today’s discourse seem tame in comparison. Thomas Jefferson in particular was prone to partisan grudges. Political arguments were often settled by duels (one of which took the life of Alexander Hamilton) or violent altercations between elected officials. Such feuds were not limited to the nation’s capital; life on the frontier was even more fractious.

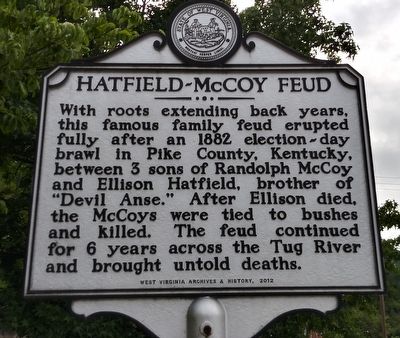

The hardy pioneers who settled Appalachia—the untamed lands now known as West Virginia, Kentucky, and Tennessee–included many of Scots-Irish descent, a clan known for having volatile tempers and “getting even.” The murderous Hatfield-McCoy feud was real, and lasted for decades. Modern-day Tennesseans pride themselves on being “nice,” but that label did not describe historical figures such as the hot-tempered Andrew Jackson and his contemporaries. It is often forgotten that two of Tennessee’s most famous statesmen–John Sevier and Andrew Jackson—were arch-enemies.

American history is littered with vehement—and often violent—disagreements: the opposition to Mormons in Ohio, Missouri, and Illinois; the bloody conflicts between abolitionists and pro-slavery forces; and the bloodbath over secession, to name a few. Our national unity was threatened, prior to the Civil War, by intense internal disagreements regarding the wisdom of the War of 1812 (which New Englanders adamantly opposed) and federal tariffs in 1828 and 1832 (which South Carolina purported to nullify). During the Gilded Age, labor disputes sometimes escalated to armed combat. The melting pot of mass immigration in the early 1900s occasionally produced conflict, as did episodes of anti-Catholic sentiment. Prior to Pearl Harbor, the nation was bitterly divided regarding U.S. involvement in WWII.

The Cold War was accompanied by McCarthyism. The 1960s saw massive unrest in cities and on college campuses as part of the civil rights movement and opposition to the Vietnam War. The 1970s witnessed tumult over women’s liberation and opposition to busing. Decades of pro-life activism led to the Supreme Court’s overruling of the controversial decision in Roe v. Wade last year.

Our history is checkered with internal conflicts: the temperance movement, the fight for women’s suffrage, opposition to the draft, Coxey’s Army marches in 1894 and 1914, the 1932 Bonus Army protest, the struggle for desegregation and racial equality, and many more. Yet the nation survived, and became stronger as a result of these conflicts.

My point is that name-calling and spirited disagreement is nothing new in America. Our discourse has always been fractious. In a democracy in which citizens enjoy freedom of expression, passionate differences of opinion are inevitable—healthy, even.