Cordell Hull: Hero or Knave?

This essay originally appeared in the Daily Times on October 9, 2023 (here).

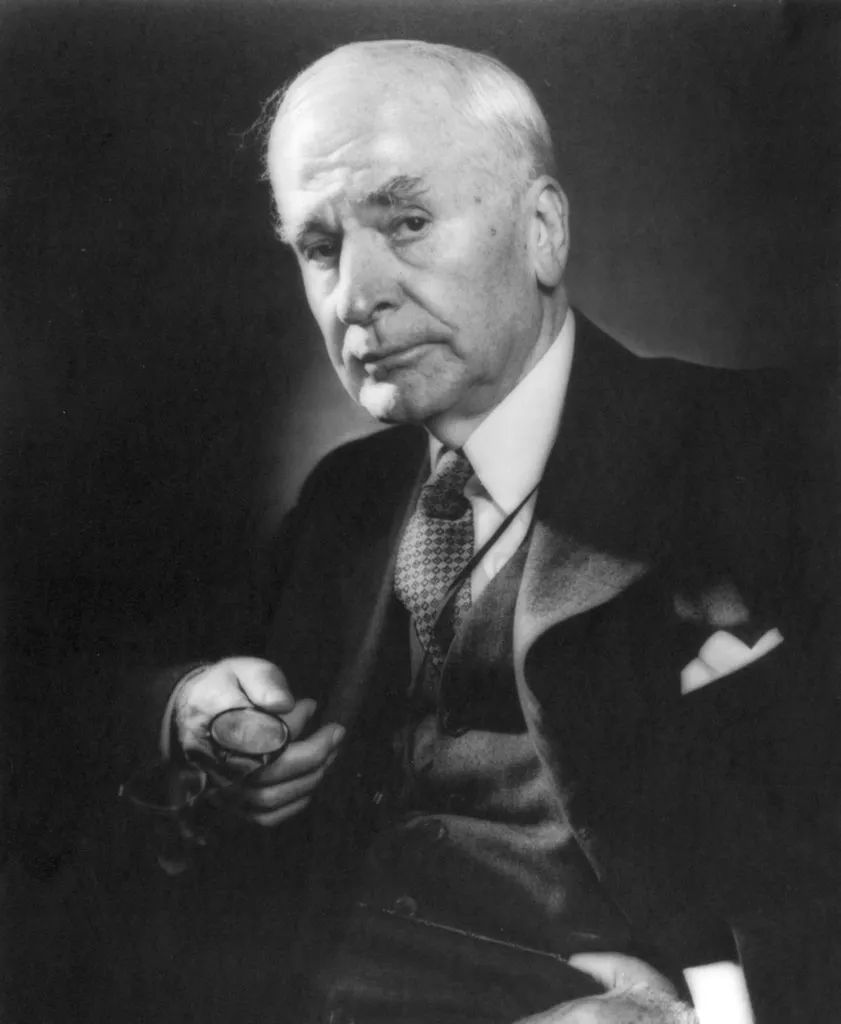

Tennessee has birthed many accomplished men and women, some of whom I have written about in prior columns. We tend to remember the frontiersmen, soldiers, and adventurers, but the rich history of the Volunteer State has produced a long roster of notables. One example is Cordell Hull, namesake of a dam on the Cumberland River, the resulting 12,000-acre lake near Carthage, a 10-story office building in Nashville where Tennessee legislators work, and a state park in Pickett County containing a refurbished representation of the log cabin where he was born in 1871. Hull is regarded by some as the most momentous public figure from Tennessee in modern times.

What did Hull, a Democrat, do to warrant these honors? He was a lifelong public servant, having served four years in the Tennessee House of Representatives, 11 terms in the U.S. House of Representatives (1907-1921, 1923-32), a brief stint in the U.S. Senate, and a term as Chairman of the Democratic National Committee. Hull sought the Democratic nomination for President at the 1928 convention, but lost to Al Smith. (Herbert Hoover won the general election.)

While in Congress, Hull was a member of the powerful Ways and Means Committee, where he fought for low tariffs and—in the wake of the 16th Amendment’s authorization of a federal income tax in 1913—authored the first version of the Internal Revenue Code. In contrast to his support for the federal income tax, Hull opposed another Progressive Era initiative, women’s suffrage, which was granted by the 19th Amendment, ratified in 1920. Hull left his Senate seat in 1933 to join the cabinet of New Deal President Franklin D. Roosevelt, where he supported free trade.

Hull’s fame as a public figure is largely due to his record-setting 11-year tenure as U.S. Secretary of State (from 1933 to 1944) under FDR. Hull’s work as diplomat was the highlight of his lengthy career. He won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1945 for his central role in creating the United Nations. Yet Hull’s stewardship of the State Department under FDR was not without controversy. Hull’s role in turning away a ship full of Jewish refugees in 1939 has blackened his reputation in the eyes of some critics.

One of the most atrocious episodes in human history, the Holocaust, took place in Nazi Germany during Adolph Hitler’s murderous reign during the 1930s and 40s. Six million Jews were rounded up, sent to concentration camps, and exterminated by the Nazis. The “Final Solution,” implemented with death camps and gas chambers, was Hitler’s chilling legacy. The West knew that genocide against European Jews was underway on a massive scale, but for a variety of reasons hesitated to act. Prior to Pearl Harbor, most Americans—still smarting from memories of WWI–opposed involvement in the hostilities overseas. Moreover, most Americans were reluctant to become the world’s lifeboat while struggling in the grip of the Great Depression.

The desire to maintain neutrality in the European conflict accounted for some of the ambivalence toward the Holocaust, but anti-Semitism may also have played a role. Hull, who was married to the daughter of an Austrian Jew, was anxious to downplay his wife’s ethnic identity, for selfish political reasons. Despite his failure at the 1928 Democratic Convention, Hull retained presidential ambitions, and in the early 20th century (in both Tennessee and America as a whole) Jews were regarded with suspicion (as were Catholics). Hull’s wife, Frances Witz, was a practicing Episcopalian but rumors about her Jewish heritage dogged the cautious, thin-skinned Hull.

Despite his enormous popularity with U.S. voters, neither could FDR himself disregard Americans’ opposition to mass immigration, and he needed the support of Southern congressional leaders to ensure his re-election in 1940. All of this factored into the controversial decision to deny asylum to a shipload of German Jews in 1939.

In May 1939, 937 Jewish refugees fled Hamburg, Germany aboard the ocean liner MS St. Louis, bound for Havana, Cuba. They hoped to escape impending doom in Nazi Germany. Most of the passengers had applied for U.S. visas, and were planning to stay in Cuba only until they could legally enter the U.S. Unbeknownst to the passengers, Cuban officials withdrew the “landing certificates” that had been issued allowing them entry to Cuba, and upon the ship’s arrival in Havana, most passengers were barred from disembarking.

Despite the pleas of the passengers, and worldwide media attention, FDR’s State Department refused to allow the St. Louis to unload its passengers in the U.S., either. According to Time magazine, Hull “strongly opposed” allowing the passengers to exit in the U.S. As a result, the ship returned to Germany, where more than a quarter of its passengers subsequently died in the Holocaust.

Hindsight is 20/20, but this incident is difficult to reconcile with a Nobel Peace Prize.