Are We “One Nation Under God”?

Some discontents are trying to dissolve the bonds that undergird our national motto: E Pluribus Unum.

This is my response to the reply essays in the Law & Liberty forum on nullification. It appeared in Law & Liberty on August 30, 2024 as “E Pluribus Unum” (here). Thanks to Real Clear Civics and The Originalism Blog (here)!

I am flattered that my essay received the thoughtful attention of a trio of fine scholars, who raise many interesting points and offer three distinct perspectives. American history is rich in nuance and has unfolded in a fascinating series of complex vignettes—fodder for generations of historians. Alas, the subject of my lead essay was ultimately quite narrow—and purely legal: Does the Constitution authorize individual states unilaterally to declare federal laws unconstitutional, and to resist their enforcement on that ground? The answer is no, and my respondents do not raise any serious arguments to the contrary. Yes, states can—and do–protest, complain, and lobby against objectionable federal laws. James Madison called this “interposition.”

Prior to ratification of the 17th Amendment, the states’ political opposition to federal laws had substantial force. I have no beef with “interposition” or other forms of political opposition to federal laws. Nullification—meaning outright defiance, such as Arkansas Governor Orval Faubus’s resistance to Brown v. Board of Education–is a different matter. That is what this debate is about.

The concept of nullification by the states is nowhere mentioned in the Constitution, was not raised during the Constitutional Convention in 1787, is not contemplated in the pro-ratification Federalist essays, and is contradicted by over 200 years of Supreme Court decisions. In fact, the Constitution was adopted, following nearly a decade under the dysfunctional Articles of Confederation, precisely to replace the unworkably loose confederation with a strong central government. Thus, nullification advocates are left to reading the “tea leaves”—fragments of history and out-of-context quotes from various founding-era figures supposedly supporting the notion that individual states have veto power over federal laws. Their case is unconvincing.

In reality, the Constitution was drafted by a committee of 55 disparate delegates (who did not include Thomas Jefferson), and ratified in state conventions with over 1600 delegates participating. There was enormous disagreement among the framers, representing the various states. The Constitution reflects a compromise among the competing factions, few of whom were perfectly satisfied with the end result. In some circles, the ambivalence continues to this day. The Constitution is not a “Jeffersonian” document, in part because Jefferson was not even present at the convention in 1787. Disgruntled critics of the Constitution can seek Jeffersonian amendments pursuant to Article V, as some scholars have suggested.

I like Tom Woods (and his co-author, Kevin Gutzman), but—with respect–I believe his essay rests on some common errors. Throughout our history, from the founding era to today, there has been a struggle between proponents of a strong national government and those who favored the primacy of the states. Philosophically, I tend to sympathize with the latter, but over time, the proponents of a strong central government have largely prevailed. As a lawyer, rather than a historian or political scientist, I accept the results of our constitutional system instead of challenging their legitimacy or embracing fanciful theories supporting alternative outcomes—a risible form of the self-serving “living Constitution” scholarship pioneered by the Left.

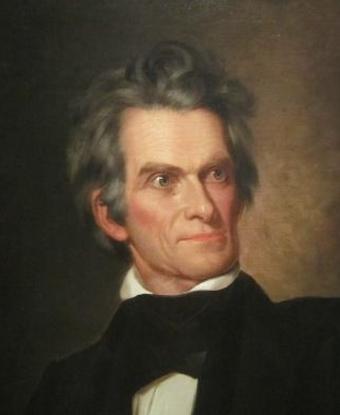

The significance of the “compact theory” touted by Woods is that by ratifying the Constitution, the states surrendered (or “delegated,” in the words of the Tenth Amendment) a portion of their sovereignty to the national government. The Anti-Federalists well understood this, and opposed the Constitution for that very reason! The issue we are addressing in this forum is how the Constitution addresses conflicts between the Constitution and a law passed by Congress that allegedly exceeds its authority under Article I. Woods echoes the unavailing arguments of the Anti-Federalists, who opposed ratification, and champions the views of John C. Calhoun, who may have sparked the disunion eventually leading to the Civil War. (Calhoun’s state, South Carolina, was the first to secede.)

Because the Constitution is the Law of the Land, a statute that violates the Constitution is void; this is undisputed. The relevant question is, who gets to decide the issue? The drafters of the Constitution were explicit, in Article III (by creating the federal judicial power) and Article VI, the Supremacy Clause. The Supremacy Clause expressly makes federal law paramount over state law. In Federalist #44, Madison explained that this was necessary to prevent the Constitution from being “annulled” by the states, and to prevent the new federal government from being “reduced to the same impotent condition” as had been the case under the Articles. Article III created courts to decide disputes involving federal law, and Art. VI subordinated the states’ role in two ways: by declaring that “every State shall be bound thereby, any Thing in the Constitution or Laws of any State to the Contrary notwithstanding,” and by requiring state officials to take an oath “to support this Constitution.”

This is not an “ex cathedra pronouncement,” but a textual exegesis. In belt-and-suspenders fashion, Art. VI makes it clear that states are not authorized to independently determine the constitutionality of federal laws. This function was reserved for the Supreme Court. Alexander Hamilton explained the need for the Supremacy Clause in Federalist #22: “To produce uniformity in these [judicial] determinations, they ought to be submitted, in the last resort, to one SUPREME TRIBUNAL.” In Federalist #33, Hamilton averred that a national union would be meaningless unless federal laws are supreme: “It would otherwise be a mere treaty, dependent on the good faith of the parties, and not a government.” Woods disagrees, arguing that the ultimate sovereigns are “the peoples of the states,” not the federal government or the states. Accordingly, he believes that the Supremacy Clause leaves submission to federal law optional on the part of the states.

Under the people-are-the-ultimate-sovereign reasoning, are all citizens entitled individually to “restrain the agent they created”? After all, aren’t both the state and federal governments the “agents” of the people? The notion of an at-will social contract is a libertarian’s dream—but not a constitution.

The oft-cited (and non-binding) Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions–mere “expressions of opinion,” according to Madison in 1800—are hardly a Rosetta Stone of the founders’ intent. They were issued in protest of an unpopular federal law, and written before judicial review was recognized in Marbury v. Madison (1803). The ghost-written resolutions, described by scholars as “ambiguous,” “nebulous,” and contradictory, were not joined by any of the 14 other states, and had no legal effect whatsoever. Some states expressly disagreed with the notion that states had the authority to determine the constitutionality of federal laws. While it is true that Madison’s position shifted over time (on this and other subjects), that is all the more reason not to treat the resolutions as holy writ.

Our constitutional structure did not emerge precocial from the convention hall in Philadelphia; it took decades of turbulent experience—and (sometimes controversial) disputes resolved by the Supreme Court–to fully mature. The path forward wasn’t always straight. Snippets from various founding-era figures do not undermine over 200 years of American history and Supreme Court caselaw.

Woods ignores some of the historical episodes cited in my essay—notably the Fugitive Slave Act and desegregation cases—and, tellingly, has nothing to say about Cooper v. Aaron. I suppose he considers these judicial decisions to be mere “propaganda” taught in law schools. I confess; as a lawyer, I “succumbed” to acknowledging 200 years of constitutional decision-making. Woods also scoffs at the prospect for internal reforms of the national government via elections and legal challenges, but the 6-to-3 conservative majority on the Supreme Court—thank you, President Trump—has made impressive inroads by overturning Roe v. Wade and Chevron, with more surely to come.

The system is working, albeit imperfectly. Recognizing this does not make me a “feckless loser,” but a citizen in a republic founded on the rule of law. Woods evidently fancies himself a modern-day George Wallace, resisting the “completely out-of-control regime” by nullification. It didn’t work in 1963 and it won’t work now. I do not dispute the growth of the federal Leviathan; nor do I defend it. My essay concerns the constitutionality of nullification, not its potential policy benefits.

Re John Grove: I agree that most nullification proposals—including Tennessee’s S.B. 2775—are “performative and unserious” and “just another form of political posturing.” I also agree that in the early days of the nascent republic, the concepts of a national government and a union among the states were embryonic. Dual sovereignty was an unprecedented and untested model for constitutional self-government. Modern conceptions of federalism were forged by various crises and conflicts in our national experience. I, too, am disappointed at various critical turns that led to our present predicament. By citing the unanimous decision in Cooper v. Aaron (1958), I did not mean to “breezily accept” it, or to uncritically defend it. I certainly do not “endorse” it. My point was that the law is settled in the same fashion as Marbury v. Madison (which has its own modern detractors).

Due to the early jurisprudence overseen by Chief Justice John Marshall, judicial review is now a feature of our constitutional system, as are the “hierarchical lines of authority leading to the central government’s Supreme Court.” History has settled certain matters, including nullification and secession. I am a realist, not a theorist (or a revisionist).

I agree wholeheartedly with Grove that “The window for making state nullification a part of the American political landscape closed long ago, and barring drastic shifts in public self-understanding, it does not seem likely to reopen any time soon. But that fact does not demonstrate the superiority of the nationalist, unitary alternative that we have followed.” Amen! The Anti-Federalists raised many valid objections to the Constitution, and in some respects their dire predictions were prescient. Sadly, “we the people” have accepted—even demanded—a larger, more powerful national government. Changing this will require more than wishful thinking. The tools are civic education, elections, the Art. V amendment process, and constitutional litigation.

Re Forrest Nabors: His reply essay conveys a sense of despair—even desperation—by describing the current political climate as a “genuinely revolutionary period” and “grave times such as ours,” that threatens our “republican form of government and way of life.” Nabors scolds me for tepid “moderation and strict obedience” to constitutional norms, and being unwilling to embrace a “counterrevolution.” Are we really on the brink of—or actually undergoing—a “revolution” leading to tyranny by “imperial rulers”? I respectfully suggest that Nabors is jumping the gun by invoking the principles of 1776—let alone 1860. Madison’s Federalist #46 supports interposition, not rebellion.

Calls for extra-constitutional resistance based on “natural right” are premature, in my estimation. President Andrew Jackson’s January 1833 proclamation makes it clear that rebellion is a last resort: “The existence of this right, however, must depend upon the causes which may justify its exercise. It is the ultima ratio, which presupposes that the proper appeals to all other means of redress have been made in good faith, and which can never be rightfully resorted to unless it be unavoidable.” (Emphasis added.) We are not there yet, and should work hard to avert that calamitous moment. I pray that day never comes.

Finally, nullification advocates dismiss concerns that willy-nilly defiance of federal law would create chaos. Tennessee’s proposed nullification bill, S.B. 2775, suggests otherwise. It would authorize nullification of—and command resistance to—purportedly “unconstitutional” federal actions (past, present, or future) by all three branches of state government: the Governor, via executive order; the entire Tennessee judiciary (trial and appellate), by disregarding federal precedents; and the General Assembly, by declaring federal laws null and void. Hundreds of Tennessee judges could not only disagree with federal precedents; they could disagree with each other! Multiply this by 50 states, if all the others followed suit, and the nation would resemble a Tower of Babel. National unity would be eviscerated. Nullification is a two-way street, and defiant blue states could play havoc with a second Trump term.

We should strive to preserve both the union and the rule of law. They are not incompatible.