Inheriting the Wind, or Reaping the Whirlwind?

The so-called “elites” have been sneering at ordinary Americans for nearly 100 years, and we’re fed up

A slightly abridged version of this essay originally appeared in Law & Liberty on July 17, 2019 (here). Thanks to Power Line!

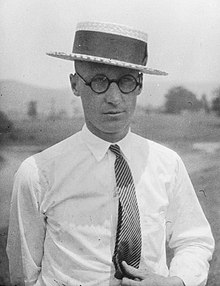

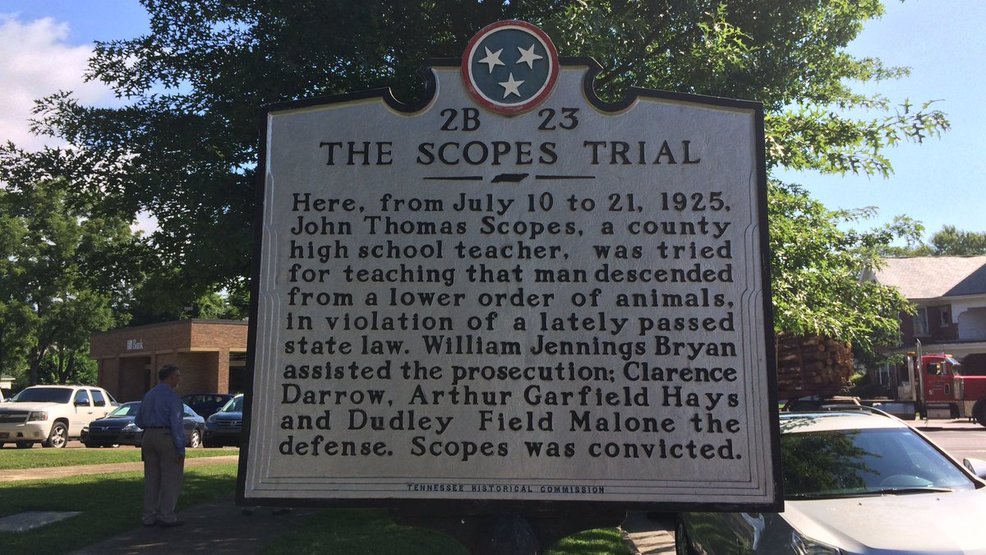

The events that occurred in Dayton, Tennessee during the summer of 1925—the so-called “Scopes Monkey Trial”—have captured the American imagination like few legal proceedings ever have. Noted trial lawyer Clarence Darrow was part of the large legal team representing a 24-year-old substitute high school teacher, John Thomas Scopes, who was accused of violating the state’s Butler Act, which prohibited the teaching of evolution in a state-funded school. The celebrity co-prosecutor was William Jennings Bryan, the three-time Democratic presidential nominee, former Nebraska congressman, and Secretary of State to President Woodrow Wilson. Both Darrow and Bryan were prominent Progressive figures. Bryan, a left-wing evangelical and a fiery orator, is best known for his “Cross of Gold” speech at the 1896 Democratic National Convention.

The trial provided an opportunity for Darrow, whose reputation had been sullied by questionable tactics employed in the defense of radical labor leaders, to vindicate himself before a national audience. Chicago’s WGN radio station broadcast the trial nationwide and hundreds of reporters, some of them from overseas, covered the case. Geoffrey Cowan, author of the exhaustively-researched book The People v. Clarence Darrow, notes that Darrow achieved national notoriety, “won the support of Eastern sophisticates,” and “found new acceptance” as a result of the widely-publicized trial, especially his alleged humiliation of Darrow’s “old hero,” Bryan. [1] This canard, which formed the dramatic crux of the 1960 movie Inherit the Wind, a highly-fictionalized depiction of the trial adapted from the 1955 play written by Jerome Lawrence and Robert E. Lee, [2] is just one aspect of the popular mythology that surrounds the case. [3]

Almost all of the “conventional wisdom” concerning the Scopes trial is false. Contrary to the impression created by Inherit the Wind and other popular accounts (including the sensational reportage of H. L. Mencken of The Baltimore Sun, one of the leading journalists of his day), the trial was not a fundamentalist inquisition, but an ill-conceived publicity stunt by Dayton businessmen who were trying to attract tourists to the small town—to put Dayton on the map. To generate a test case challenging the statute, the American Civil Liberties Union had offered to defend any teacher charged with violating the Butler Act, gratis. Dayton businessmen recruited Scopes to agree to serve as the defendant, even though he was unsure he had actually taught evolution. Nonetheless, Scopes volunteered to be charged. The trial—for a misdemeanor offense—was staged. Celebrity lawyers were solicited to participate for the sole purpose of increasing public interest in the case. The Baltimore Sun paid part of the defense’s expenses because it knew that the spectacle would sell newspapers, and it did. A lot of them.

If the goal was to stimulate interest in Dayton, it worked. For eight days, the town was the focus of worldwide attention. [4] During the trial, the population of Dayton swelled from about 1800 to about 5000, with a raucous carnival atmosphere. Yet the trial was cut-and-dried; the jury deliberated only nine minutes before rendering a guilty verdict. Scopes was fined $100. The Tennessee Supreme Court promptly reversed the conviction on a technicality, [5] and the state chose not to retry the case. Tennessee eventually repealed the Butler Act.

The eight-day show trial was a media circus, but little else. It resolved no factual disputes, established no new law, and settled no constitutional issues. It was a purely manufactured controversy—a radio-era precursor to reality TV and cable news. Bizarrely, Bryan died in his sleep (at age 65) five days after the trial ended. Instead of putting Dayton on the map in a positive way, the case left the town in undeserved ignominy.

Many plot features of Inherit the Wind—which was conceived during the Cold War as an anti-McCarthyism allegory—were entirely fabricated. Scopes (Bertram Cates) was not arrested in class and was never jailed; there was no unhinged fundamentalist preacher (Rev. Jeremiah Brown) exhorting the town; the trial was not accompanied by lynch mobs; Scopes/Cates was never burned in effigy and had no conflicted fiancée; and Bryan (Matthew Harrison Brady) was not a deranged buffoon or hysterical fanatic. Whatever one thinks about Bryan’s political or economic views, scholars regard him as one of the most important figures of the Progressive Era, and even as one of the most influential American politicians who never served as president. His portrayal in Inherit the Wind (by Fredric March) as an incompetent windbag is a disgraceful farce.

What the trial did represent, then and now, is a showdown between religious belief and secularism—as symbolized by the theory of evolution. In 1925, America was still a largely rural, deeply-religious nation. The urban elites, represented by eastern intellectuals and journalists who covered the trial, despised the small town “rubes,” “yokels,” and “morons”— Mencken scornfully called them the “booboisie”—who populated small towns like Dayton (or rural states such as Tennessee, for that matter). The elites had particular contempt for the rubes’ religiosity. To the sanctimonious “city slickers,” the Scopes trial was a momentous struggle between fundamentalism and modernity. The press corps overwhelmingly was rooting for modernity. At the trial, Darrow, an atheist, openly mocked belief in the Bible, calling it “foolish,” “fool religion,” and the refuge of “bigots and ignoramuses.”

The highlight of the trial in Inherit the Wind is when the Darrow character (portrayed as a hero by Spencer Tracy, of Father Flanagan fame) [6] slyly manipulates the egotistical Bryan character into foolishly taking the witness stand as an expert on the Bible, and then humiliates him on cross-examination as the ignorant Bryan becomes flustered and angry. This scene perfectly captures the disdain of secular elites toward people of faith, which continues to this day. (Recall recent references in political campaigns to “deplorables” and “irredeemables” who “cling to guns or religion.”) The trouble is, the pivotal scene is grossly inaccurate. What actually occurred at the trial is quite different.

While there was an exchange between Darrow and Bryan, a devout Presbyterian, it lasted for only two hours, outside of the presence of the jury, and was ultimately stricken from the record by the trial judge as “irrelevant.” Some accounts describe Darrow’s questioning of Bryan as “insulting and abusive.” [7] Moreover, Bryan agreed to the unusual colloquy, not out of vanity, but because he understood that Darrow would reciprocate—that is, submit to questioning by Bryan in turn regarding his beliefs. [8] Bryan felt the worldwide coverage of the trial would expose Darrow’s anti-religious bias in an unflattering light. The courtroom afforded a valuable media opportunity—a pulpit or stage with national reach. However, the judge’s abrupt—but proper–ruling that Bryan’s testimony was irrelevant unexpectedly prevented Darrow from having to take the stand. And, whereas the movie version makes it appear that Darrow’s questioning of Bryan was impromptu and spontaneous, in fact the questions were carefully prepared in advance and even rehearsed with surrogates outside of court.

Wishing to keep the eloquent Bryan from having an opportunity to summarize his case to the jury—and the world, via radio—Darrow waived the defense’s summation, [9] which prevented the prosecution from presenting Bryan’s carefully-prepared closing remarks, which included these lines:

Science is a magnificent force, but it is not a teacher of morals. It can perfect machinery, but it adds no moral restraints to protect society from the misuse of the machine. It can also build gigantic intellectual ships, but it constructs no moral rudders for the control of storm-tossed human vessels. It not only fails to supply the spiritual element needed but some of its unproven hypotheses rob the ship of its compass and thus endanger its cargo….If civilization is to be saved from the wreckage threatened by intelligence not consecrated by love, it must be saved by the moral code of the meek and lowly Nazarene. His teachings, and His teachings alone, can solve the problems that vex the heart and perplex the world.

In Inherit the Wind, Bryan/Brady is unfairly presented as a ridiculous fool—a pathetic figure. Bryan’s words show that he was thoughtful, decent, and—for his time—wise, albeit uninformed. [10] And he won the case, beating the man regarded as one of the most formidable courtroom advocates of all time. Bryan was not so much an opponent of evolution as he was of Social Darwinism, and the Nietzschean philosophy he felt it represented.

Unfortunately, Bryan’s legacy as a man of faith has been besmirched by Hollywood’s willingness to distort history in the aid of promoting a secular agenda. The left’s disdain for religion and religious belief has only gained momentum since 1925. From simply mocking piety, the elite intelligentsia has progressed to banning prayer in public schools, forbidding aid to religious schools, removing religious symbols from public property, deeming Judeo-Christian morality to be “irrational,” and persecuting Christian bakers (and other vendors) for honoring their religious consciences. In 2016, the American voters—arguably the heirs to the long-ridiculed citizens of Dayton—rose up and pushed back.

The Scopes trial, so badly mischaracterized in Inherit the Wind, better illustrates another Biblical verse, “For they have sown the wind, and they shall reap the whirlwind.” [11]

[1] Geoffrey Cowan, The People v. Clarence Darrow 443-44 (1993).

[2] The movie, directed by Sidney Kramer and starring Spencer Tracy as Darrow (shown as a character called Henry Drummond), was nominated for several Academy Awards, including Best Actor. Ironically, the title of the movie (and the play) is derived from a Bible verse, Proverbs 11:29.

[3] Ted McAllister addressed this subject for Law and Liberty a few years ago in “The Scopes Trial and the Problem of Democratic Control.”

[4] Visitors are still attracted to the historic courthouse, which houses a museum commemorating the “trial of the century” held there in 1925.

[5] Scopes v. State, 154 Tenn. 105 (1927).

[6] Tracy won an Academy Award for Best Actor in that role in Boys Town (1938).

[7] See Robert W. Cherny, A Righteous Cause 179 (1985).

[8] See Jeffrey P. Moran, The Scopes Trial 143 (2002). Before taking the stand, Bryan indicated his intention to later call Darrow to testify, and the trial judge agreed, stating “Call anybody you desire. Ask them any questions you wish.” Moran notes that “Although Bryan’s testimony surely did not go as well as he had hoped, neither did it go as poorly as legend seems to have it.” Id. at 160. Reporters sympathetic to Darrow spun the encounter as an embarrassing defeat for fundamentalism.

[9] That Darrow would waive his summation—normally a showcase for legendary oratorical skills—demonstrates that he “had no interest in persuading a jury or, for that matter, the people of Tennessee—his audience was the informed elite of America, most of whom lived in the cities of the Northeast.”

[10] The acerbic Mencken denounced Bryan, even in death, as “a charlatan, a mountebank, a zany without sense or dignity.” Cherny, supra note 7, at 184.

[11] Hosea, 8:7.