What Really Threatens American Labor

This essay originally appeared in Law & Liberty on July 15, 2020 (here), in response to a lead essay by Richard Epstein (here). Thanks to Real Clear Markets!

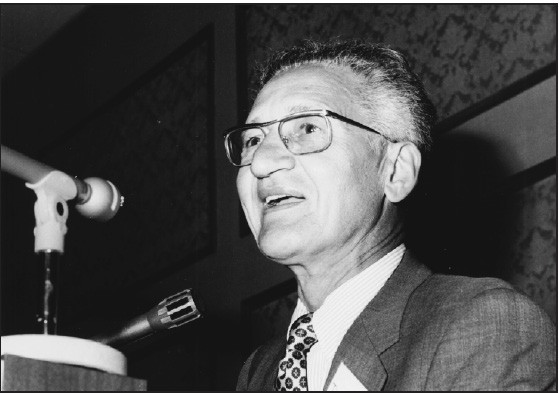

Richard Epstein has been challenging conventional wisdom in the academy since he burst onto the scene as an enfant terrible in the 1970s. (This is intended as a compliment.) No longer so “enfant,” Epstein’s vigor and virtuosity are undiminished. A polymath who has demonstrated mastery of many different subjects, Epstein’s scholarship in the area of labor law is especially noteworthy. His 1983 article in the Yale Law Journal, “A Common Law for Labor Relations,” is a classic, as is the 1984 symposium issue of The University of Chicago Law Review that he organized, entitled “The Conceptual Foundations of Labor Law,” containing another gem, his article “In Defense of the Contract at Will.”

As my own modest contributions to this topic indicate, I largely agree with Epstein. In particular, I concur that it is an egregious mistake for conservatives to promote revitalized private-sector unionization in the name of a pro-worker “industrial policy.” To avoid duplication, I will briefly make some complementary points.

First, opposition to labor unions is not a libertarian versus conservative issue. I am not a libertarian, but I find Epstein’s analysis of labor unions compelling. One need not be a Randian or Nozickian, or an anarchist or proponent of the “minimal state,” to oppose the model of labor relations represented by the National Labor Relations Act. Nor does one have to pledge blind devotion to the sanctity of free markets to agree with Epstein’s critique. Indeed, from the advent of the New Deal until quite recently, conservatives of all stripes criticized the NLRA model of collective bargaining and labor union abuses generally. (Henry Simons’ famous article, “Some Reflections on Syndicalism,” was written 1941 and published in the Journal of Political Economy in 1944.)

The New Deal has long been anathema to the Right, and I am puzzled that some reform-cons now find inspiration in it. It is ironic that Epstein, after arguing with liberals in the legal academy for decades, now finds himself squaring off against center-right reformers.

Second, Epstein’s critique of labor unions is neither unique nor definitive. Other scholars, approaching the subject from a variety of backgrounds—classical liberals, labor economists, labor law specialists, and historians—have reached conclusions similar to Epstein’s, while not necessarily following the same analytical path: Sylvester Petro, Thomas Haggard, Paul Moreno, Morgan Reynolds, Howard Dickman, Philip Bradley, Edwin Vieira, and W.H. Hutt are just a few examples. This is not an appeal to authority so much as a roll call of sources for curious readers wishing to explore the subject further.

As Petro explained in The Labor Policy of the Free Society (1957) and later articles, the prevailing common law paradigm in the U.S. prior to and during the Industrial Revolution—displaced by the Norris-LaGuardia Act (1932) and the NLRA (1935)—did not ban labor unions or even peaceful strikes; Commonwealth v. Hunt (1842) merely protected the right of employers to hire non-union employees willing to work on terms refused by the union. The concerted action of employees seeking higher wages was never subjected—for that reason alone–to the stringent provisions of antitrust laws applicable to business combinations. The NLRA laid waste to that sensible common law regime.

Third, there are many practical objections to unionization as it currently exists in the United States, in addition to theoretical and philosophical criticisms:

Beginning with the threshold concept of “exclusive representation,” and continuing with the unions’ right to compel the payment of monies by non-members as a condition of employment, and the abrogation of employers’ common law rights to resist unionization, the NLRA fundamentally rests on coercion. Moreover, exclusive representation enables unions to engage in arbitrary and even discriminatory treatment of individual workers with limited legal recourse.

Employees should have the right to withhold their services, individually or in concert, if they find working conditions unsatisfactory, but they have no right to threaten or assault other workers willing to cross a picket line. Yet such violence is—and long has been–an inherent feature of strikes, and the remedies provided by the NLRA are wholly inadequate.

Collective bargaining under the NLRA explicitly rests on the Marxian notion that businesses inevitably exploit labor, a sentiment unions fuel to maintain polarization and labor strife. Hamstringing the employers’ entrepreneurial initiatives and management prerogatives hampers innovation and efficiency.

The monopoly status and legal privileges conferred on labor unions ineluctably produce a lack of transparency and accountability, leading to widescale corruption (the UAW prosecutions being only the most recent example), rent-seeking that distorts the labor market, and the use of compelled dues to influence the political process. Factions are bad for democracy. As Simons prophetically wrote, “Monopoly power must be abused. It has no use save abuse.”

In addition, the National Labor Relations Board—the administrative agency that interprets and enforces the NLRA—was a precursor to the administrative state and remains an ossified example of New Deal hubris. The NLRA, enacted before the passage of now-ubiquitous laws governing minimum wages, maximum hours, workplace safety, employment discrimination and harassment, and the like, is antiquated and obsolete. Massive changes in the American economy have rendered unions irrelevant as well, explaining the free-fall in private-sector membership.

As Epstein points out, the larger problem is the indefensible—but unfortunately widespread—phenomenon of public-sector unionism, which cites the NLRA as its inapt precedent. Re-vitalizing private-sector unions will only strengthen their government employee counterparts, with potentially disastrous results.

Fourth, and finally, it is a fallacy to suppose that labor unions help workers (at least workers as a whole), or that collective bargaining (as we know it) is the only mechanism for improving the economic well-being of middle-class wage earners. I am not unsympathetic to the plight of working-class Americans, but I am skeptical that it is feasible to implement a centrally-planned “industrial policy” in a fractious—and often-gridlocked–representative democracy. Our federal system (intentionally, and rightly) complicates unitary decision-making, and–as the presidency of Donald Trump has demonstrated–the Beltway establishment has become captured by powerful special interests and is resistant to centralized control.

The biggest threat to middle-class wage-earners is forcing them to compete against vast numbers of low-paid, unskilled immigrants (not just the millions here illegally); ill-considered and one-sided trade deals that decimated once-prosperous manufacturing centers by exporting jobs to China, Mexico, and other countries; and the proliferation of the so-called “gig economy” which relegates many young adults to dead-end part-time positions as “independent contractors,” without fringe benefits, job security, or even statutory protections for workers categorized as employees. Independent contractor status is, for most gig workers, a form of peonage.

Having Grubhub, Uber Eats, or DoorDash deliver meals, Instacart or similar services deliver groceries, and so forth certainly provides convenience for consumers, but also creates a precarious serf class of low-paid service workers who are unlikely to achieve middle-class status. A healthy polity cannot exist without a viable middle class. The perceived lack of upward mobility, combined with enormous income inequality, leads many millennials and Gen Z voters to be attracted to democratic socialism. Ironically, one of the chief attractions of IC status for tech companies is that workers characterized as ICs are not eligible to unionize.Thus, the outdated NLRA is arguably an impediment to the economic security of 21st century workers.

This last point surely puts me at odds with Epstein and doctrinaire libertarians, perhaps proving that opposition to labor unions is not limited to devotees of the Cato Institute and the Libertarian Party, as Michael Lind has suggested.