Tennessee’s Failed Utopian Colony

This essay originally appeared in the Daily Times, on May 11, 2023 (here).

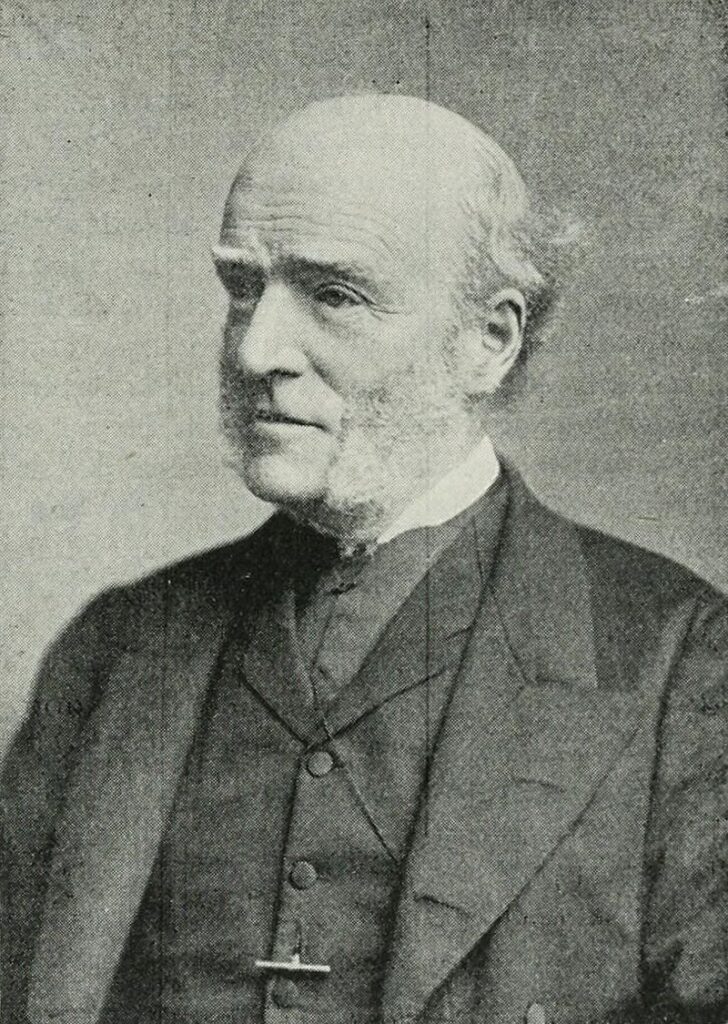

When one thinks of Tennessee’s pioneering settlers, one tends to think of folks like John Sevier, Andrew Jackson, Sam Houston, and Davy Crockett—tough farmers, soldiers, and frontiersmen, often of Scots-Irish descent—not dreamy British socialists seeking to create a utopian society. Yet, just an hour northwest of Knoxville, atop the Cumberland Plateau, lies the authentically-preserved village of Rugby, founded by well-known author and reformer Thomas Hughes in 1880 as a cooperative, class-free agricultural community for younger sons of English gentry who, like himself, were dispossessed by the medieval British custom of primogeniture—in which the first-born son inherits the family’s entire estate.

Unlike other early settlers, Hughes was primarily an intellectual, inspired by the writings of transcendentalist philosopher Ralph Waldo Emerson. The exotic notion of utopian communities—thought to offer an escape from the growing encroachment of urban life and industrialization–was popular in 19th century America. Some utopian colonies were polyamorous (Oneida, New York), while the Shakers were celibate. Many utopian experiments involved communal (or “cooperative”) ownership of property, and most were religious. For a variety of reasons, they all failed.

Rugby, named after Hughes’ progressive alma mater in Warwickshire, England, was conceived as an experiment to relocate England’s “second sons” to an area of scenic beauty where they could live as gentleman farmers, avoiding the social and economic ills plaguing Victorian England while at the same time enjoying the culture and comfort to which their class was accustomed. Straddling Morgan and Scott counties, the colony of Rugby was laid out like an English village, and many of the original buildings—painstakingly restored and now strictly protected–still stand in a unique blend of British Isles and Appalachia. The utopian colony did not fare as well.

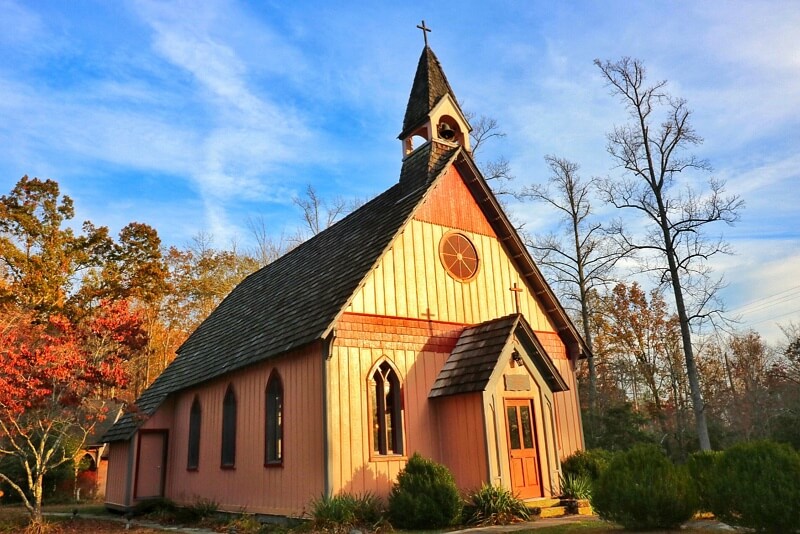

Hughes’ novel experiment attracted enormous attention when Rugby was founded, receiving coverage in both American and British publications, including the New York Times, Harper’s Weekly, The Spectator, Saturday Review, and Punch. Initially, the colony was a success. At its peak, in 1884, Rugby boasted over 300 residents, a large hotel, a tennis team, croquet courts, a social club, a literary and dramatic society, a library, and even its own newspaper, The Rugbeian, which was edited by an Oxford graduate. True to its English heritage, Rugby established an Episcopal church (still in operation).

Alas, like all utopian experiments, reality proved to be an insurmountable obstacle. In his zeal to achieve a perfect society, Hughes and his team overlooked many basic challenges that less-educated homesteaders would have identified, starting with the area’s rolling hills and poor, thin soil, which were unsuitable for agriculture. Rugby’s location, while beautiful and resort-like, was mediocre as farmland. Moreover, the village was located seven miles from the nearest railroad stop (in what is now Elgin), which rendered access difficult. Also, the colony’s ambitious planners faced protracted lawsuits over land titles, and the Plateau’s native Appalachians, suspicious of the colony’s backers, refused to sell their property.

Central planning failed to anticipate a typhoid outbreak that killed seven colonists and interrupted tourism. In 1884, fires destroyed Rugby’s main resort hotel, halting the colony’s burgeoning tourist economy and damaging the backers’ credit. A tomato canning operation was attempted, but Rugby’s “gentlemen farmers”—more gentlemen than farmers—failed to produce enough tomatoes to keep it operational. There were other setbacks. The well-meaning colonists made poor pioneers. It is reported that “A dairy failed. A sheep-raising endeavor failed. Pottery and brick-making efforts failed.” Utopia was not forthcoming, even in Tennessee.

Like all much-ballyhooed experiments, disappointments led to recrimination. According to one account, “Newspapers began to ridicule Rugby, with London’s Daily News accusing Hughes of creating a ‘pleasure picnic’ rather than a functioning colony.” The adverse publicity deterred further emigration to Rugby, and when a number of prominent colonists died in 1887, an exodus began. Many colonists returned to England or moved elsewhere in the United States. Within a decade of its founding, the utopian colony was defunct.

Fortunately, enough colonists (and their descendants) remained to preserve 20 original buildings in the village, which is operated by a non-profit organization formed in 1966 that runs a “visitor centre” (with British spelling), offers tours of four historic buildings, and hosts dozens of special events throughout the year. The village, surrounded by the Big South Fork National River and Recreation Area, is a quaint, quiet gem nestled in the picturesque hills of East Tennessee. Hiking trails abound. It is a short drive from Knoxville, but overnight lodging (decorated in period furniture) is available.

Rugby is inhabited by around 70 full-time residents. Visiting is like going back in time. One can almost envision the idealistic colonists in the 1880s, seeking to achieve utopia amidst virgin forests, clear air, and scenic gorges. They were not as hardy as their counterparts in Cades Cove, but they left behind a beautifully-preserved trove of buildings as a monument to their good intentions—and the folly of utopia.